The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 2

- Climate and Dendrochronology PowerPoint

- Grading Rubric

According to National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the years 2015-2018 were the warmest recorded on Earth in modern times! And it is only expected to get warmer. Temperatures in the Northeastern U.S. are projected to increase 3.6°F by 2035. Every year the weather is a bit different, and some years there are more extremes with very hot or cold temperatures. Climate gives us a long-term perspective and is the average weather, including temperature and precipitation, over at least 30 years.

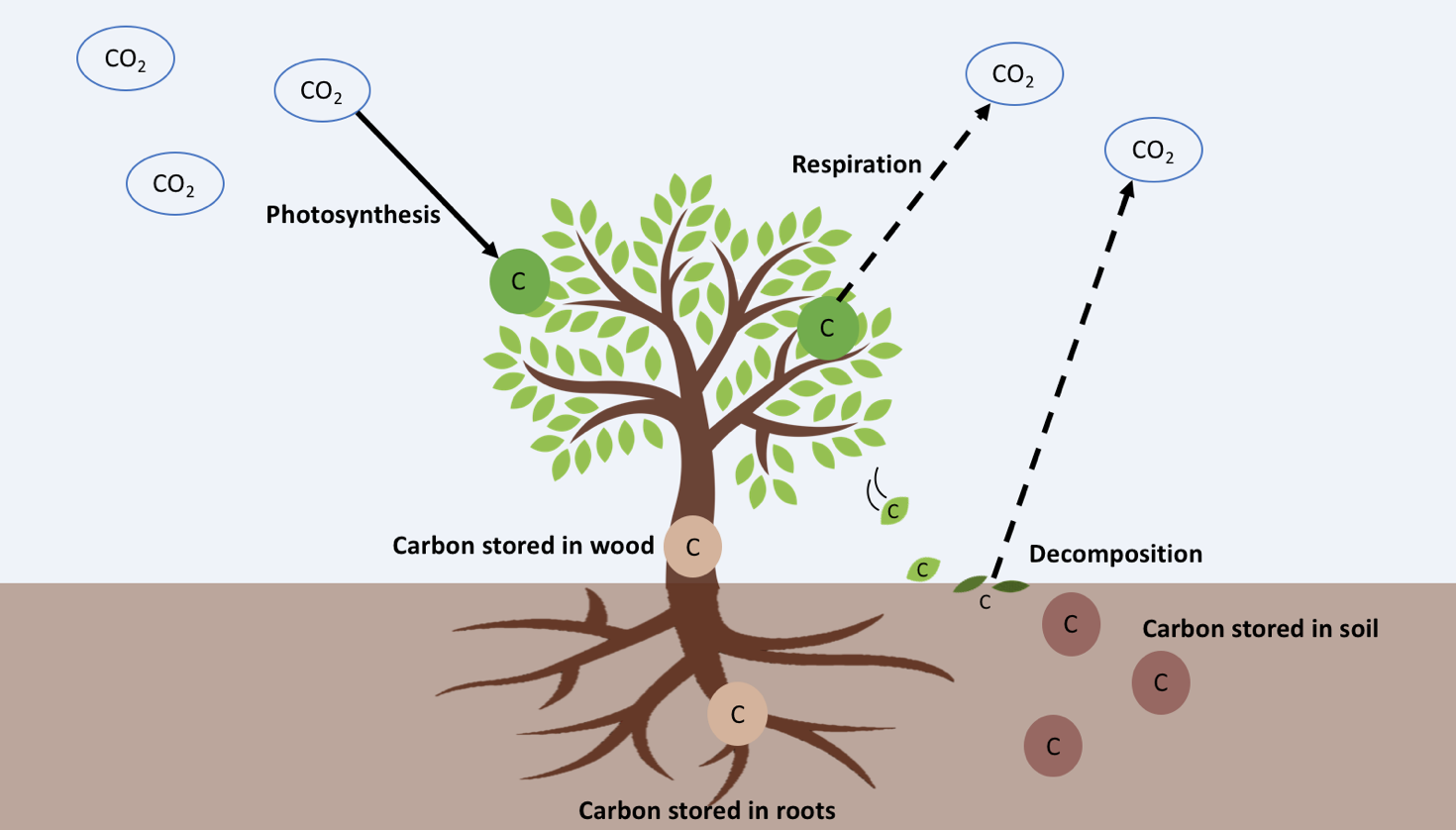

Over thousands of years, tree species living in each part of the world have adapted to their local climate. Trees play an important role in climate change by helping cool the planet – through photosynthesis, they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and evaporate water into the air.

Scientists are very interested in learning how trees respond to rapidly warming temperatures. Luckily, trees offer us a window into their lives through their growth rings. Growth rings are found within the trunk, beneath the bark. Each year of growth has two parts that can be seen: a light ring of large cells with thin walls, which grows in the spring; and a dark layer of smaller cells with thick walls that forms later in the summer and fall. Ring thickness is used to study how much the tree has grown over the years. Dendrochronology is the use of these rings to study trees and their environments.

Different tree species have different ranges of temperatures and rainfall in which they grow best. When there are big changes in the environment, tree growth slows down or speeds up in response. Scientists can use these clues in tree’s rings to decipher what climate was like in the past. There is slight variation in how each individual tree responds to temperature and rainfall. Because of this, scientists need to measure growth rings of multiple individuals to observe year-to-year changes in past climate.

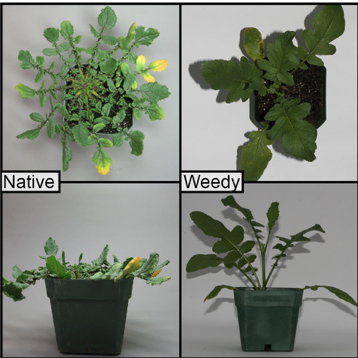

Jessie and Neil are two scientists who use tree rings for climate research. Jessie entered the field of science because she was passionate about climate change. As a research assistant, Neil saw that warming temperatures in Mongolia accelerated growth in very old Siberian pine trees. When he later studied to become a scientist, he wanted to know if trees in the eastern U.S. responded to changes in climate in the same way as the old pine trees in Mongolia. As a result, there were two purposes for Jessie’s and Neil’s work. They wanted to determine if there was a species that could be used to figure out what the climate looked like in the past, and understand how it has changed over time.

Jessie and Neil decided to focus on one particular species of tree – the Atlantic white cedar. Atlantic white cedar grow in swamps and wetlands along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts from southern Maine to northern Florida. Atlantic white cedar trees are useful in dendrochronology studies because they can live for up to 500 years and are naturally resistant to decay, so their well-preserved rings provide a long historical record. Past studies of this species led them to predict that in years when the temperature is warmer, Atlantic white cedar rings will be wider. If this pattern holds, the thickness of Atlantic white cedar rings can be used to look backwards into the past climate of the area.

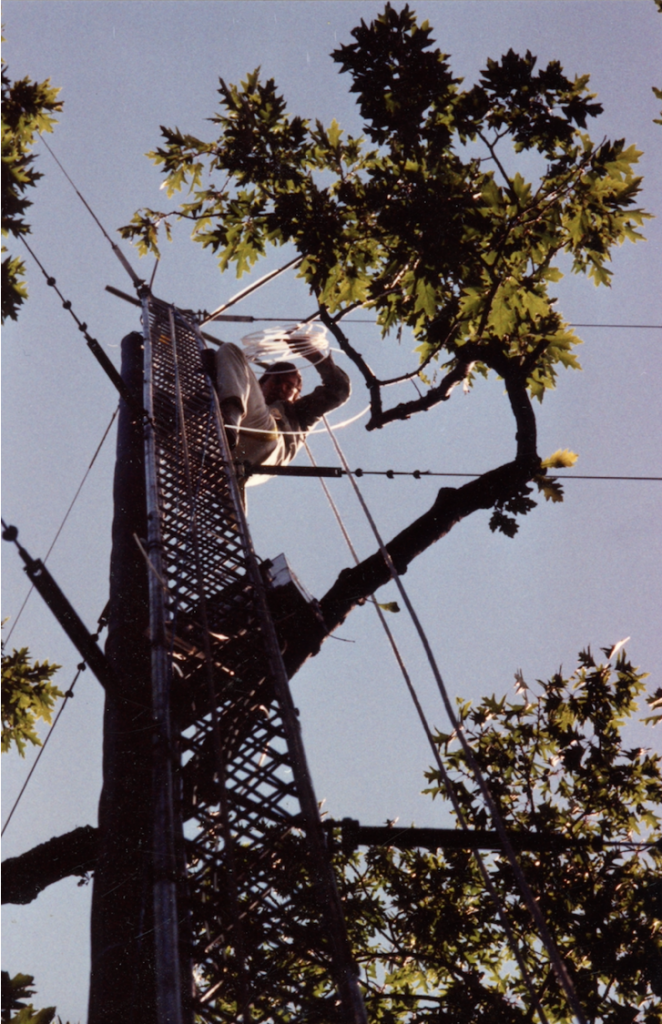

To test this prediction, Jessie and Neil needed to look at tree rings from many Atlantic white cedar trees. Jessie used an increment borer, a specialized tool that drills into the center of the tree. This drill removes a wood core with a diameter about equal to that of a straw. She sampled 112 different trees from 8 sites, and counted the rings to find the age of each tree. She then crossdated the wood core samples. Crossdating is the process of comparing the ring patterns from many trees in the same area to see if they tell the same story. Jessie used a microscope linked to a computer to measure the thickness of both the early and late growth to the nearest micrometer (1 micrometer = 0.001 millimeter) for all rings in all 112 trees. From those data she then calculated the average growth of Atlantic white cedar for each year to create an Atlantic white cedargrowth index for the Northeastern U.S. She combined her tree ring data with temperature data from the past 100 years.

Featured scientists: Jessie K Pearl, University of Arizona and Neil Pederson, Harvard University. Written by Elicia Andrews.

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 9.9

Suggestions for inquiry surrounding this Data Nugget:

- Set up a field plot on your campus to identify and monitor the diameter of different trees growing. If you have access to an increment borer, sandpaper and dissection scope you can have students date and complete a lab activity by crossdating trees.

- Hands on lesson using wood cookies “What can tree rings tell us about climate?” by Chicago Botanic Garden.

- Join, set up and participate in School Yard Ecology LTER Program by Harvard Forest.

- Explore various climate profiles of various regions.

- Webinar exploring how plants respond to climate change, featuring this Data Nugget and LTER scientists!

These videos, demonstrating the science of dendrochronology, could be a great way to spark class discussions: