The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 1

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 1

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 1

- Grading Rubric

Éste Data Nugget también está disponible en Español:

- Actividad para estudiantes, Tipo de gráfica A

- Actividad para estudiantes, Tipo de gráfica B

- Actividad para estudiantes, Tipo de gráfica C

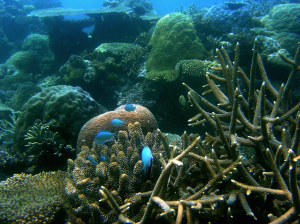

Corals are animals that build coral reefs. Coral reefs are home to many species of animals – fish, sharks, sea turtles, and anemones all use corals for habitat! Corals are white, but they look brown and green because certain types of algae live inside them. Algae, like plants, use the sun’s energy to make food. The algae that live inside the corals’ cells are tiny and produce more sugars than they themselves need. The extra sugars become food for the corals. At the same time, the corals provide the algae a safe home. The algae and corals coexist in a relationship where each partner benefits the other, called a mutualism: these species do better together than they would alone.

When the water gets too warm, the algae can no longer live inside corals, so they leave. The corals then turn from green to white, called coral bleaching. Climate change has been causing the Earth’s air and oceans to get warmer. With warmer oceans, coral bleaching is becoming more widespread. If the water stays too warm, bleached corals will die without their algae mutualists.

Carly is a scientist who wanted to study coral bleaching so she could help protect corals and coral reefs. One day, Carly observed an interesting pattern. Corals on one part of a reef were bleaching while corals on another part of the reef stayed healthy. She wondered, why some corals and their algae can still work together when the water is warm, while others cannot?

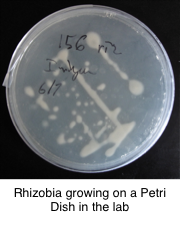

Ocean water that is closer to the shore (inshore) gets warmer than water that is further away (offshore). Perhaps corals and algae from inshore reefs have adapted to warm water. Carly wondered whether inshore corals are better able to work with their algae in warm water because they have adapted to these temperatures. If so, inshore corals and algae should bleach less often than offshore corals and algae. Carly designed an experiment to test this. She collected 15 corals from inshore and 15 from offshore reefs in the Florida Keys. She brought them into an aquarium lab for research. She cut each coral in half and put half of each coral into tanks with normal water and the other half into tanks with heaters. The normal water temperature was 27°C, which is a temperature that both inshore and offshore corals experience during the year. The warm water tanks were at 31°C, which is a temperature that inshore corals experience, but offshore corals have never previously experienced. Because of climate change, offshore corals may experience this warmer temperature in the future. After six weeks, she recorded the number of corals that bleached in each tank.

Featured scientist: Carly Kenkel from The University of Texas at Austin

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 8.0

There are two scientific papers associated with the data in this Data Nugget. The citations and PDFs of the papers are below.

- Kenkel CD, E Meyer, MV Matz (2013) Gene expression under chronic heat stress in populations of the mustard hill coral (Porites astreoides) from different thermal environments. Molecular Ecology 22:4322-433

- Kenkel CD, G Goodbody-Gringley, D Caillaud, SW Davies, E Bartels, MV Matz (2013) Evidence for a host role in thermotolerance divergence between populations of the mustard hill coral (Porites astreoides) from different reef environments. Molecular Ecology 22:4335-4348

If your students are looking for more data on coral bleaching, check out HHMI BioInteractive’s classroom activity in which students use authentic data to assess the threat of coral bleaching around the world. Also, check out the two videos below!

- A video in BioInteractive’s “Scientists at Work” series showing researchers working on the same hypothesis in another part of the world: Steve Palumbi & Megan Morikawa Study Coral Reef Damage in American Samoa

- Another BioInteractive video, appropriate for upper level high school classrooms. Visualizes the process of coral bleaching at different scales. Video includes lots of complex vocabulary about cells and the process of photosynthesis.