The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

- Grading Rubric

Chevak is a village that sits along the Ningliqvak River in Alaska. The area around the village is a flat coastal wetland, a landscape of winding river channels, marshes, and salty lakes. In the Yup’ik language, this low-lying terrain is called maraq. Here, salt-tolerant grasses and sedges thrive in an environment with brackish water, which is saltier than fresh water, but less salty than sea water. These wetlands serve as nesting grounds for waterfowl during the spring and summer months.

Further upland, the higher ground that sits roughly three meters in elevation is called nunapik, meaning tundra. Brackish water does not usually touch these areas. The tundra has many freshwater lakes and supports a different plant community, rich with forbs, shrubs, and lichen. Because it experiences less flooding, more types of plants can live in the upland tundra, providing important resources for food and medicine.

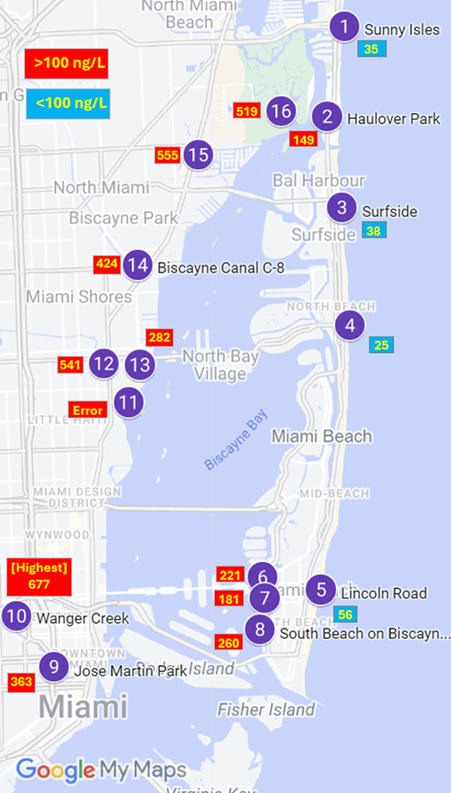

In recent years, coastal flooding has become more common near Chevak. Protective sea ice melts earlier each year. Storm surges and rising sea levels now push brackish water further inland. These flooding events increase erosion, damage property, and alter the delicate balance of wetland and tundra ecosystems.

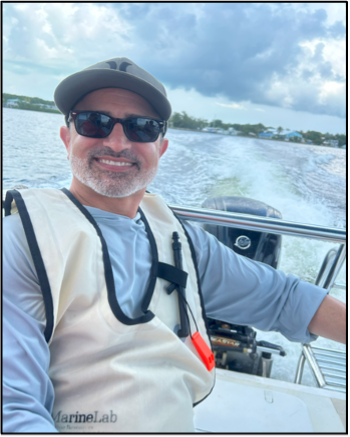

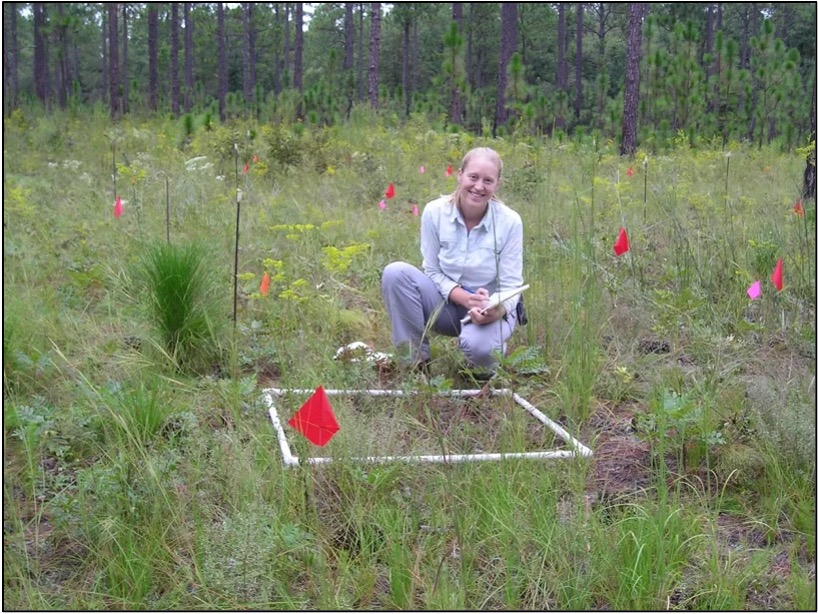

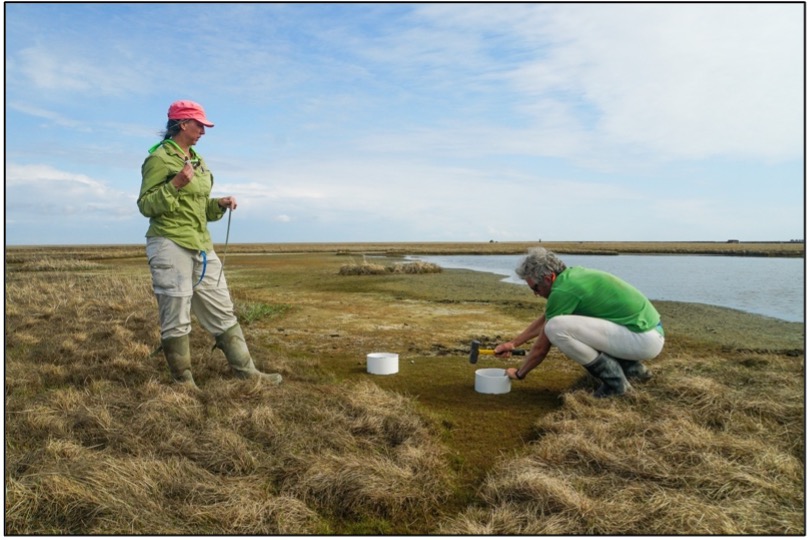

Ecologists Karen, Kathy, and Josh began studying the plants around Chevak to better understand how flooding affects these ecosystems. To understand how plant communities at high and low elevations respond to flooding, the scientists designed an experiment at Old Chevak, the original village site abandoned decades ago due to flooding.

Working in collaboration with the Chevak community and the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge, they established experimental plots to simulate flooding. The flooded plots were created by pumping in seawater to simulate high-tide flooding. This was repeated 3 times during the summer. Karen, Kathy, and Josh also kept control plots where no brackish water was added. The treatments were repeated at both high and low elevation sites. There were 7 replicates at each location.

At the summer’s end the team collected data on plant growth. They measured the biomass, or weight, of all plants in all of the plots. Karen, Kathy, and Josh grouped the plants into 4 groups. Graminoids, which include grasses and sedges, are the dominant plant group of the maraq. They typically grow well in flooded wetland areas. Forbs are broadleaf herbs, like salmonberries, that grow well in the nunapik. Shrubs include species such as blueberries, cranberries, and tundra tea. Like forbs, they also grow well in the nunapik. Lichens are plant-like species that form low crusts along the ground and are only found in the higher elevation sites.

Karen, Kathy, and Josh thought that plants from the low elevation sites would be made up of more salt and flood-tolerant species and would therefore be less harmed by frequent floods. On the other hand, high elevation sites would consist mostly of plant species that are not salt or flood-tolerant and would not do well during floods.

Featured scientists: Karen Beard (she/her) of Utah State University, Kathy Kelsey (she/her) of the University of Colorado Denver and Joshua Leffler (he/him) of South Dakota State University. Written by: Andrea Pokrzywinski (she/her).

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 8.9

Additional Resources:

This activity pairs with another Data Nugget, “Salmonberries in our future”, which features this same collaboration, but focuses on one culturally significant type of Arctic plant, salmonberries.

Additional video resources and lesson extensions can be found at the project website “Working Together”, including the following:

- “Voices from the Land” introduces the collaboration between scientists and Yup’ik community members. They are working together to respect and care for the land. This narrative is told by the students from Bethel and Chevak Alaska.

- “Mapping Merbok” describes the questions scientists are researching to document how increased flooding, such as that from Typhoon Merbok, will drive landscape changes.

- “Warming and Flooding on the Tundra” describes the research scientists are conducting to measure the impact of both warming and flooding on plant communities.