- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 2

- Scientist Profile on Project Biodiversify

- Grading Rubric

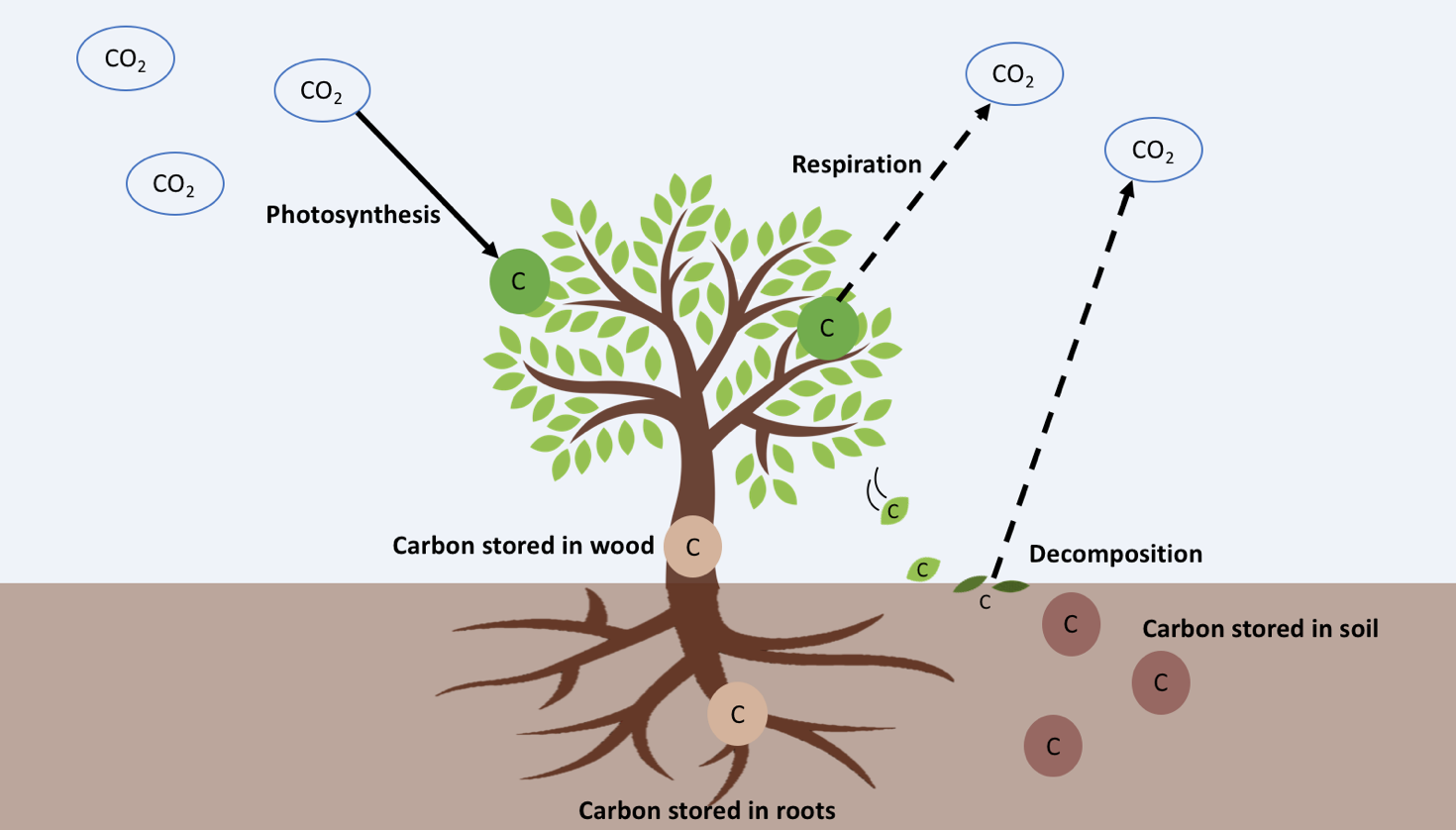

When an organism grows in different environments, some traits change to fit the conditions. For example, if a houseplant is grown in the shade, it might grow to stretch out long and thin to reach as much light as possible. If that same plant were grown in the sun, it would grow thicker stems and more leaves that are not spread as far apart. This response to the environment helps plants grow in the different conditions they find themselves in.

Flexibility is especially important when a plant is living in a harsh environment. One such environment is serpentine soils. These soils are created from the weathering of the California state rock, Serpentinite. Serpentine soils have high amounts of toxic heavy metals, do not hold water well, and have low nutrient levels. Low levels of water and nutrients found in serpentine soils limit plant growth. In addition, a high level of heavy metals in serpentine soils can actually poison the plant with magnesium!

Combined, these qualities make it so that most types of plants are not able to grow on serpentine soils. However, some plant species have traits that help them tolerate these harsh conditions. Species that are able to live in serpentine soils, but can also grow in other environments, are called serpentine-indifferent.

Alexandria has been working with serpentine soils since 2011 when she was first introduced to them during an undergraduate research experience with her ecology professor. Alexandria was especially intrigued by this challenging environment and how organisms are able to thrive in it, even with the harsh characteristics.

To learn more, she started to read articles about previous research on plants that can only grow in serpentine soils. Alexandria learned that these plant species are generally smaller than closely related species. This was interesting, but she still had questions. She noticed the other experiments had compared plant size in different species, not within one species. She thought the next step would be to look at how plants that are the exact same species would respond to serpentine and non-serpentine soil environments. To explore this question, she would need to use serpentine-indifferent plant species because they can grow in serpentine soils and other soils.

Just as a houseplant grows differently in the sun or shade, plants grown in serpentine and non-serpentine soils might change to survive in their environment. Alexandria thought one of these changes could be happening in the roots. She decided to focus on plant roots because of their importance for plant survival and health. Roots are some of the first organs that many plants produce and anchor them to the ground. Throughout a plant’s life, the roots are essential because they bring nutrients to above-ground organs such as leaves. Because serpentine soils have fewer plant nutrients and are drier than non-serpentine soils, Alexandria thought that plants growing in serpentine soils may not invest as much into large root systems. She predicted plants growing in serpentine soils will have smaller roots than plants growing in non-serpentine soils.

To test her ideas, she studied the effects of soil type on a serpentine-indifferent plant species called Dot-seed plantain. She purchased seeds for her experiment from a local commercial seed company. About 5 seeds were planted in serpentine or non-serpentine soils in a growth chamber where growing conditions were kept the same. After the seedlings emerged, the plants were thinned so that there was one plant per pot. The only difference in the environment was the soil type. This allowed Alexandria to attribute any differences in root length to serpentine soils. At the end of her experiment, she pulled the plants out of the soil and measured the root lengths of plants in both treatments.

Featured scientist: Alexandria Igwe (she/her) from University of Miami

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 8.7

Additional resources related to this Data Nugget:

The topics described in this Data Nugget are similar to the published research in the following article:

- Igwe, A.N. and Vannette, R.L. 2019. Bacterial communities differ between plant species and soil type, and differentially influence seedling establishment on serpentine soils. Plant Soil: 441: 423-437

There is a short video of Alexandria (Allie) sharing her research on serpentine soils.

There have been several news stories and blog posts about this research: