Frozen lady beetles.

The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 2

- PowerPoint of images and chill coma video

- Grading Rubric

- Digital Data Nugget on DataClassroom

Éste Data Nugget también está disponible en Español:

- Actividad para estudiantes, Tipo de gráfica A

- Actividad para estudiantes, Tipo de gráfica B

- Actividad para estudiantes, Tipo de gráfica C

Walking across a snowy field or mountain, you might not notice many living things. But if you dig into the snow, you’ll find a lot of life!

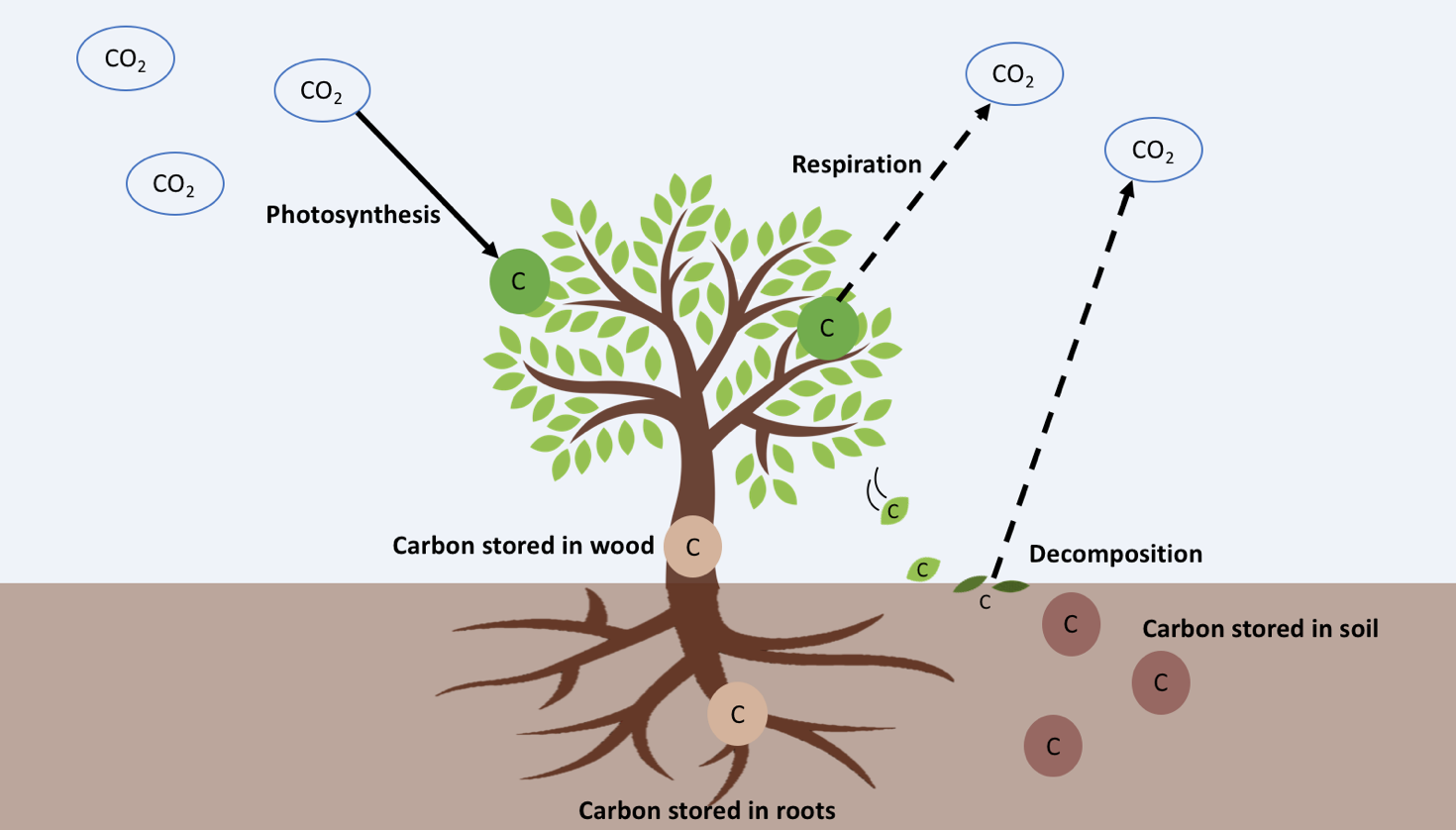

Until recently, climate change scientists thought warming in winter would be good for most species. Warmer winters would mean that species could avoid the cold and would not need to deal with freezing temperatures as often or for as long. Caroline is a scientist who is thinking about winter climate change in a whole new way. Snow covers the soil, acting like an insulating blanket. Many species rely on the snow for protection from the winter’s cold. When temperatures climb in the winter, snow melts and leaves the soil uncovered for longer periods of time. This leads to the shocking pattern that warmer temperatures actually means the soil gets colder!

Caroline is interested in how species that rely on the snow will respond to climate change. She studies a species of insect called lady beetles. Lady beetles are ectotherms, meaning their body temperature matches that of their environment. Because climate change is reducing the amount of snow in the lady beetle habitat, Caroline wanted to know how they would respond to these changes.

Caroline and her team, Andre and Nikki, decided to investigate what happens to lady beetles when they are exposed to longer periods of time in cold temperatures. When soil temperatures drop below freezing (0℃), lady beetles go into a chill coma, or a temporary, reversible paralysis. When temperatures are below freezing, it is so cold that they are unable to move. When temperatures rise back above freezing, they wake from their chill comas. When lady beetles are in chill comas, they are easier for predators to catch because they can’t escape. They are also unable to find food or mates. Scientists can measure how fast it takes lady beetles to recover from chill coma, called chill coma recovery time, and use this as a measure of their performance.

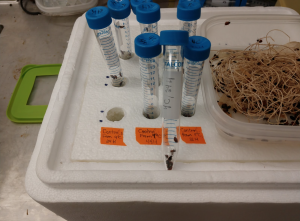

Beetles in their pre-testing habitat are on the right; tubes with beetles about to be immersed in a cooler filled with crushed ice are on the left.

They designed an experiment to test whether the amount of time lady beetles spend in freezing temperatures affects how long it takes them to wake up from a chill coma. Caroline thought that lady beetles exposed to lengthy freezing temperatures would be harmed because freezing causes tissue damage and the insect must use more energy to survive. She predicted that the longer the lady beetles had been exposed to the cold, the longer it would take them to wake up from their chill comas.

To begin the experiment, Andre and Nikki placed groups of lady beetles in tubes. They then placed the tubes in an ice bath, bringing the temperature down to 0℃, the point when lady beetles enter chill coma. They varied the amount of time each tube was in the ice baths and tested chill coma recovery times after 3, 24, 48, 72, or 96 hours. After removing the tubes from the ice baths, they put the lady beetles on their backs with their legs in the air and left them at room temperature, 20℃. Andre and Nikki timed how long it took each beetle to wake up and turn itself over.

In the experiment, they used two different populations of lady beetles. Population 1 had been living in the lab for several weeks before the experiment began. They were not in great health and some had started to die. In order to make sure they had enough beetles for the experiment, Caroline purchased more lady beetles, which she called Population 2. Population 2 only spent a few days living in the lab before testing and were in much better health. Caroline noted the differences in these populations and thought their age, health, and background might affect how they respond to the experiment. She decided to track which population the lady beetles were from so she could analyze the data separately and see if the health differences between Population 1 and 2 changed the results.

Featured scientists: Caroline Williams & Andre Szejner Sigal, University of California, Berkeley, & Nikki Chambers, Biology Teacher, West High School, Torrance, CA

About Nora: Nora is currently an undergraduate getting her B.S. in Zoology with a concentration in Zoo and Aquarium as well as a minor in Marine Ecosystem Management from Michigan State University. Although aquatic life is her main interest, she think it’s important to appreciate other animal groups and take a break to play and explore the nature around you. That curiosity was how she was able to volunteer in labs on campus from entomology to genetics, and how she came to spend a summer at the Kellogg Biological Station in Michigan.

About Nora: Nora is currently an undergraduate getting her B.S. in Zoology with a concentration in Zoo and Aquarium as well as a minor in Marine Ecosystem Management from Michigan State University. Although aquatic life is her main interest, she think it’s important to appreciate other animal groups and take a break to play and explore the nature around you. That curiosity was how she was able to volunteer in labs on campus from entomology to genetics, and how she came to spend a summer at the Kellogg Biological Station in Michigan.