Image of a red fox caught on one of the wildlife cameras.

The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

- PowerPoint of wildlife camera images

- Grading Rubric

- Digital Data Nugget on DataClassroom

For most of our existence, humans have lived in rural, natural places. However, more and more people continue to move into cities and urban areas. The year 2008 marked the first time ever in human history that the majority of people on the planet lived in cities. The movement of humans from rural areas to cities has two important effects. First, the demand that people place on the environment is becoming very intense in certain spots. Second, for many people, the city is becoming the main place where they experience nature and interact with wildlife on a regular basis.

Remington and Grant are city-dwellers and have been their entire lives. Remington grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma and Grant is from Cleveland, Ohio. In Tulsa, Remington fell in love with nature while running on the trails of city parks during cross country and track practices. Grant developed a love for nature while fishing and hiking in the Cleveland Metroparks in Ohio. These experiences led them to study wildlife found in urban environments because they believe that cities can be places where both humans and wildlife thrive. However, to make this belief a reality, scientists must understand how wildlife are using habitats within a city. This knowledge will provide land managers the information they need to create park systems that support all types of species. However, almost all research done on wildlife takes place in natural areas, like national parks, so there is currently very little known about wildlife habits in urban areas. To address this gap in knowledge, Remington, Grant, and their colleagues conduct ecological research on the urban wildlife populations in the Cleveland Metroparks.

Remington prepares to attach the camera to a buckeye tree. He secures them with a heavy-duty lock to keep the cameras safe from theft by people using the parks.

The Cleveland Metroparks are a collection of wooded areas that range in size, usage, and maintenance. Some are highly used small parks with mowed grass, while others are large, rural parks with thousands of acres of forest and miles of winding trails. As they began studying the Metroparks, they noticed the parks were like little “islands” of wildlife habitat within a large “sea” of buildings, pavement, houses and people. This reminded Remington and Grant of a fundamental theory in ecology: the theory of island biogeography. This theory has two components: size and isolation of islands. The first predicts that larger islands will have higher biodiversity because there are more resources and space to support more wildlife than smaller areas. The second is that islands farther away from the mainland will have lower biodiversity because more isolated islands are harder for wildlife to reach. Remington and Grant wondered if they could address this first component in the wide variety of areas that are part of the Cleveland Metroparks. If the theory holds for the Metroparks, it could help them to figure out where most species live in the park system and help managers better maximize biodiversity. It would also provide an important link between ecological research conducted in natural areas and urban ecology.

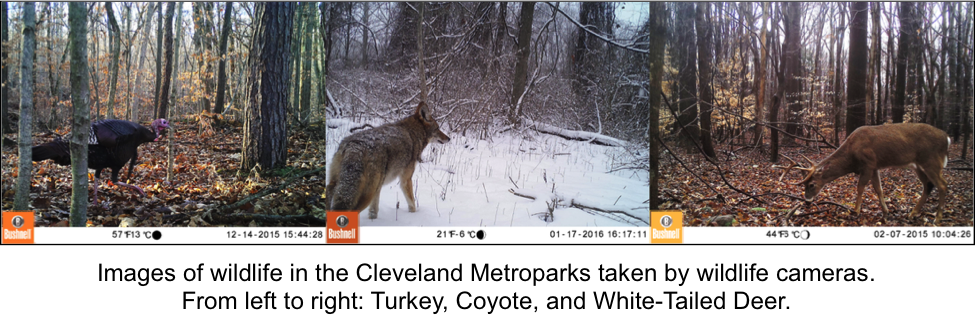

To evaluate whether the theory of island biogeography holds true in urban areas, Remington and Grant set up 104 wildlife cameras throughout the parks. These cameras photograph animals when triggered by motion. They used these photographs to identify the locations of wildlife in the parks and to get a count of how many individuals there are, known as their abundance. With these data, they tested whether the size of the park would influence biodiversity as predicted by the theory of island biogeography.

One challenge with measuring “biodiversity” is that it means different things to different people. Remington and Grant looked at two common measurements of biodiversity. First, species richness, which is the number of different species observed in each park. Second, they calculated the Shannon Wiener Index of biodiversity for each park. This index incorporates both species richness and species evenness. Species evenness tells us whether the abundances of each species are similar, or if one type is most common and the others are rare. Evenness is important because it tells you whether a park has lots of animals from many different species or if most animals are from a single species. If a park has greater evenness of species, the Shannon-Wiener index will be higher.

Featured scientists: Remington Moll and Grant Woodard from Michigan State University

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 11.4

Additional teacher resource related to this Data Nugget:

- Remington and Grant have made their data available for use in classrooms. If you would like to have your students work with raw data, it can be used to calculate the Shannon Wiener Index, or explore other aspects of species richness and evenness in the parks. This data is not yet published, so keep in mind this data is intended only for classroom use. Download the Excel file here!

- PowerPoint slideshow of images from the wildlife cameras in the Cleveland Metroparks.

- Citizen science Zooniverse site where students can view data and identify species from Remington and Grant’s cameras.

- For more background on the importance of biodiversity, students can eat this article in The Guardian – What is biodiversity and why does it matter to us?

About Remington: Remington is a Ph.D. student and NSF Graduate Research Fellow at Michigan State University in Dr. Bob Montgomery’s lab. Prior to Michigan State, Remington received B.S. and M.S. degrees from the University of Missouri, where he worked with Dr. Josh Millspaugh. Following his M.S., he spent time in Amman, Jordan doing work with the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature and spent three years teaching high school biology, chemistry, and theology at the Beirut Baptist School in Lebanon.

About Remington: Remington is a Ph.D. student and NSF Graduate Research Fellow at Michigan State University in Dr. Bob Montgomery’s lab. Prior to Michigan State, Remington received B.S. and M.S. degrees from the University of Missouri, where he worked with Dr. Josh Millspaugh. Following his M.S., he spent time in Amman, Jordan doing work with the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature and spent three years teaching high school biology, chemistry, and theology at the Beirut Baptist School in Lebanon.

He uses cutting-edge technologies such as GPS collars and camera-traps to study predator-prey interactions between large carnivores and their prey. He is particularly excited about evaluating how ecological theory developed in “natural” areas like national parks applies to urban contexts. Remington grew up in the city and fell in love with nature and ecology in city parks. Although it carries substantial challenges, Remington believes that humans and large predators can peaceably coexist, even in and around cities. It is his goal to use the lessons learned in his research to help make that belief a reality.