The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

- Grading Rubric

Pollination is one of nature’s most important processes. Without pollen moving from one plant to another, many plants would not be able to produce fruits or seeds. Without pollination, we wouldn’t have food like apples, strawberries, or even chocolate! But not all pollination works the same way. Some plants rely on pollinators like bees and butterflies, while others can reproduce without any help at all. Scientists are still exploring why plants have these different strategies.

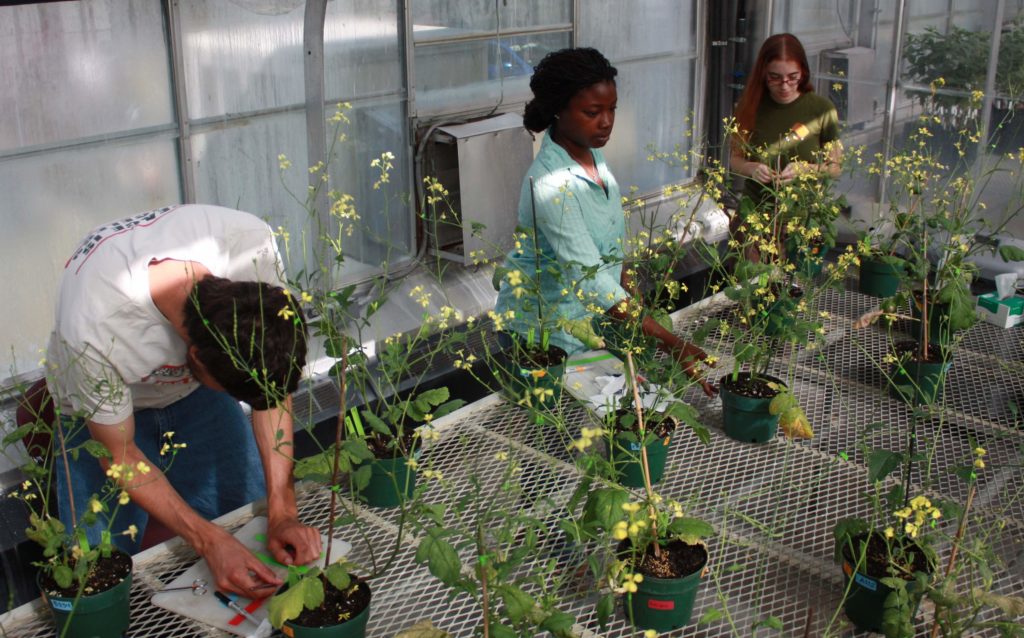

As a science teacher, Cynthia is always looking for ways to bring real science into her classroom. To learn more about the work of scientists, she joined a summer research program. While there, she had the opportunity to design and carry out a study on pollination in a plant species, Mexican petunia.

Mexican petunias are a flowering plant found in gardens, parks, and wild spaces. They have bright purple flowers. This plant has two ways it can be pollinated, called pollination methods. First, insect pollinators visit and move pollen. When pollen is moved from one plant to another, this is called outcrossing. Second, these plants can self-pollinate, meaning pollen from a single flower can pollinate that same flower.

Pollination methods make a big difference for plants. Outcrossing mixes the genetics of two different plants together, which creates new genetic combinations that may help offspring survive and thrive. In contrast, self-pollination means the genetics of the plant are the same as the parent plant and no new genetic combinations are made. Plants that use self-pollination don’t need to rely on pollinators, however many times the seeds they produce are not viable and are not able to grow.

Cynthia predicted that outcrossing would produce the most fruits and seeds, and flowers that relied on self-pollination would produce fewer seeds. She designed a garden experiment where she could control how Mexican petunias were pollinated. To set up her study, she used four different treatments.

Bagged – Cynthia put mesh bags around the petunia flowers. This prevents pollination from other plants, so this treatment shows whether flowers are able to successfully self-pollinate on their own.

Open pollination – Cynthia left these flowers open to visits from insects. These plants could be self-pollinated or outcrossed.

Self-pollinated by hand – Cynthia hand-pollinated these flowers using pollen from another flower on the same plant. This treatment shows whether the plant produces fruit when the flowers are self-pollinated by hand.

Outcrossed by hand – Cynthia hand-pollinated these flowers with pollen from a different Mexican petunia plant. These plants are all outcrossed.

Cynthia monitored the Mexican petunia plants in her four treatments for three weeks. She checked the flowers every few days to see which ones developed fruit. If a flower made a fruit, she counted the number of seeds per fruit. In the open pollination treatment, a few times the fruit opened and launched out its seeds before Cynthia could count them, meaning she could get fruit data from the flower, but not a seed count. At the end of her experiment, she had collected data on percent fruit development, or the chance of successful development of a fruit from a flower, and the number of seeds produced within those fruits, called seed count.

Featured scientist: Cynthia Nuñez from Florida International University