The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

- Grading Rubric

Humans are changing the earth in many ways. First, by burning fossil fuels and adding greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere we are causing climate change, or the warming of the planet. Scientists have documented rising temperatures across the globe and predict an increase of 3° C in Michigan within the next 100 years. Second, we are also changing the earth by movingspecies across the globe, introducing them into new habitats. Some of these introduced species spread quickly and become invasive. Invasive species harm native species and cost us money. There is also potential that these two changes could affect one another; warmer temperatures from climate change may make invasions by plants and animals even worse.

All living organisms have a range of temperatures they are able to survive in, and temperatures where they perform their best. For example, arctic penguins do best in the cold, while tropical parrots prefer warmer temperatures. The same is true for plants. Depending on the temperature preferences of a plant species, warming temperatures may either help or harm that species.

Katie, Mark, and Jen are scientists concerned that invasive species may do better in the warmer temperatures caused by climate change. There are several reasons they expect that invasive species may benefit from climate change. First, because invasive species have already survived transport from one habitat to another, they may be species that are better able to handle change, like temperature increases. Second, the new habitat of an invasive species may have temperatures that allow it to survive, but are too low for the invasive species to do their absolute best. This could happen if the invasive species was transported from somewhere warm to somewhere cold. Climate change could increase temperatures enough to put the new habitat in the species’range of preferred temperatures, making it ideal for the invasive species to grow and survive.

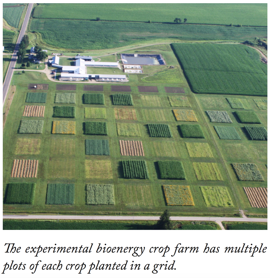

To determine if climate change will benefit invasive species, Katie, Mark, and Jen focused on one of the worst invasive plants in Michigan, spotted knapweed. They looked at spotted knapweed plants growing in a field experiment with eight rings. Half of the rings were left with normal, ambient air temperatures. The other half of the rings were heated using ceramic heaters attached to the side of the rings. These heaters raised air temperatures by 3° C to mimic future climate change. At the end of the summer, Mark and Katie collected all of the spotted knapweed from the rings. They recorded both the (1) abundance, or number of spotted knapweed plants within a square meter, and (2) the biomass (dry weight of living material) of spotted knapweed. These two variables taken together are a good measure of performance, or how well spotted knapweed is doing in both treatments.

Featured scientists: Katie McKinley, Mark Hammond, and Jen Lau from Michigan State University

This Data Nugget was adapted from a data analysis activity developed by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC). For a more detailed version of this lesson plan, including a supplemental reading, biomass harvest video and extension activities,

This Data Nugget was adapted from a data analysis activity developed by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC). For a more detailed version of this lesson plan, including a supplemental reading, biomass harvest video and extension activities,