The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

- Powerpoint of images

- Scientist Profile on Project Biodiversify

- Scientist Profile

- Grading Rubric

For millions of years, monarch butterflies have been antagonizing milkweed plants. Although adult monarchs drink nectar from flowers, their caterpillars only eat milkweed leaves, which harms the plants. This is an ecological interaction called herbivory. The only food for monarchs is milkweed leaves, meaning they have evolved to be highly specialized, picky eaters. But their food is not a passive victim. Like most other plants, milkweeds fight back with defenses against herbivory.

Monarch butterflies lay their eggs on the underside of milkweed leaves. After eggs hatch, caterpillars start to feed and quickly meet the plant’s first defense. Milkweed leaves are covered in thousands of tiny hairs, called trichomes, that the caterpillar needs to shave off before they can take a bite. The next challenge happens when the caterpillar takes a bite of the leaf. They get a mouthful of latex, which is sticky like Elmer’s glue. The caterpillars have to be very careful in how they feed. They cut the veins in the leaf to drain out the latex before continuing to feed on the leaf. Even after monarch caterpillars make it past the trichomes and latex, there’s another defense they need to overcome. Milkweed leaves have chemical toxins called cardiac glycosides, which are poisonous to most animals. As they feed, monarchs eat some of this poison.

Anurag is a scientist who has long been fascinated by plants and their defenses. He thinks this comes from the fact that his mother was such an avid gardener. She would grow food, such as peppers, squashes, and tomatoes. He looks back and has memories that are associated with garden plants and their defenses. For example, he remembers eating a bitter cucumber as a kid and spitting it out. He also can still recall the bitter aroma on his hand after brushing against the sticky tomato leaves. And plants that are tough and stringy, like kale, are not as tasty to eat. These traits are examples of plant defenses in action, making them harder or less enjoyable to eat, reducing herbivory.

Anurag first started studying milkweeds 20 years ago, based on a recommendation from a friend. His friend told him of the bitter, sticky, and furry leaves that were treasured by the monarch butterfly caterpillars. This led him to study the paradox of coevolution. The milkweed and monarch have such a tight relationship that over time, milkweeds have evolved multiple ways to defend themselves against their herbivores. In response, monarchs have evolved to overcome those defenses because they need to eat the milkweed. This arms race may continue to shift back and forth over the course of evolutionary time.

This back-and-forth battle between caterpillar and plant intrigued Anurag. He wanted to know whether milkweed’s defensive traits are still effective against monarchs, or have monarchs evolved in ways that make them unaffected by the defenses? Because each defense trait might be at a different phase in the coevolution process, perhaps some would be effective defenses to herbivory, but others would not be effective. He predicted that monarchs would be harmed by all three milkweed defense traits (trichomes, latex, and cardiac glycosides), but that some would cause more harm than others.

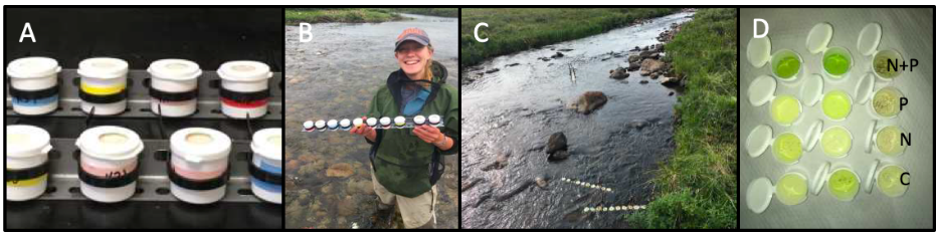

To test his ideas, Anurag and his collaborators grew monarch caterpillars on 24 different North American milkweed species. They put a single newly hatched caterpillar on each plant and had five replicate plants per milkweed species. They recorded each caterpillar’s growth over the course of 5 days to see how healthy it was. They also measured the amount of trichomes, latex, and cardiac glycosides in each plant to determine their level of defense. Once they had their data, they looked for a relationship between caterpillar growth and plant defense traits to determine which made the best plant defenses. The better the defense, the less caterpillars would grow.

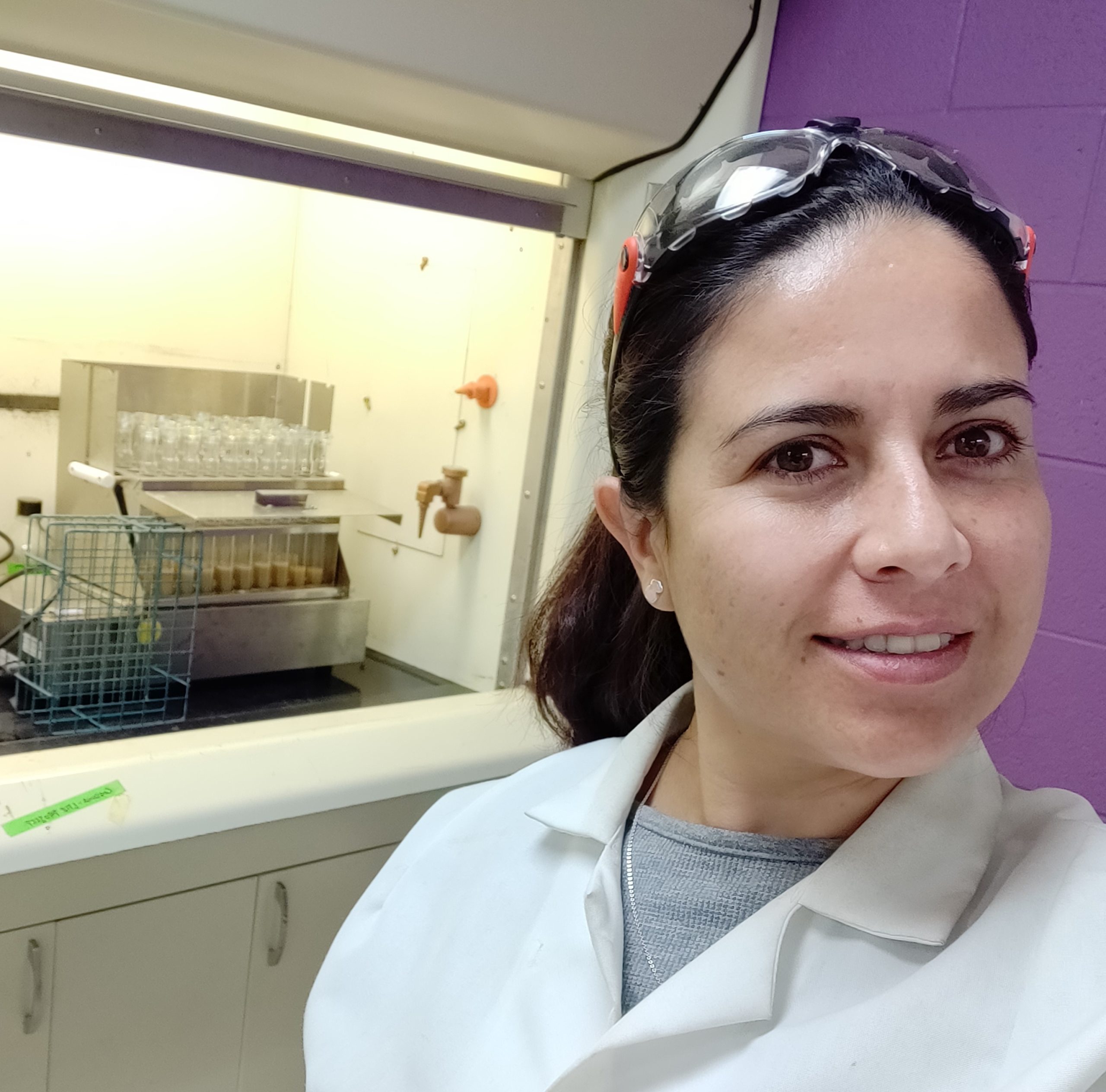

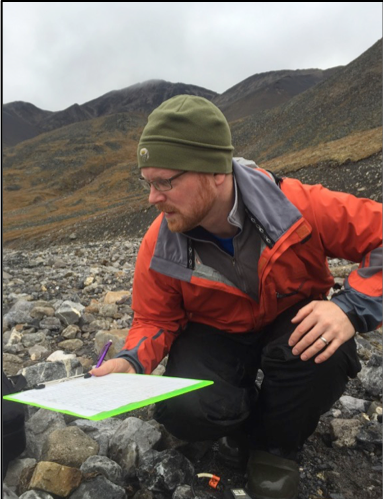

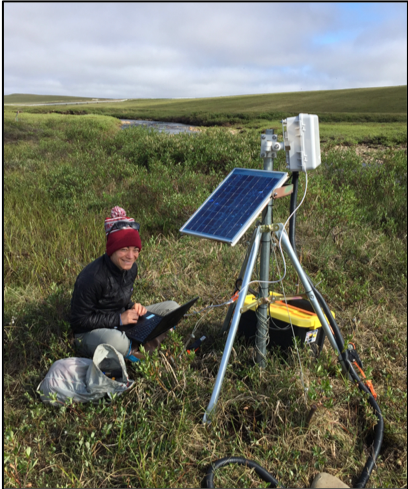

Featured scientist: Anurag Agrawal (He/Him/His) from Cornell University

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 8.5

Additional teacher resources related to this Data Nugget include:

- Anurag has other examples, data, and related stories in his book: Monarchs and Milkweed, which is written for budding scientists and interested naturalists: www.amazon.com/dp/0691166358.

- Students can learn more about Anurag, his research, and his lab at his website: www.herbivory.com which includes blog posts about monarch conservation, the community of insects on milkweed plants, videos of talks and presentations, and other things related to his research and teaching at Cornell University.

- A scientific article based on this research: Agrawal, A. A., Fishbein, M., Jetter, R., Salminen, J. P., Goldstein, J. B., Freitag, A. E., & Sparks, J. P. (2009). Phylogenetic ecology of leaf surface traits in the milkweeds (Asclepias spp.): chemistry, ecophysiology, and insect behavior. New Phytologist, 183(3), 848-867.

- Learn more about Anurag and his research in this YouTube video!