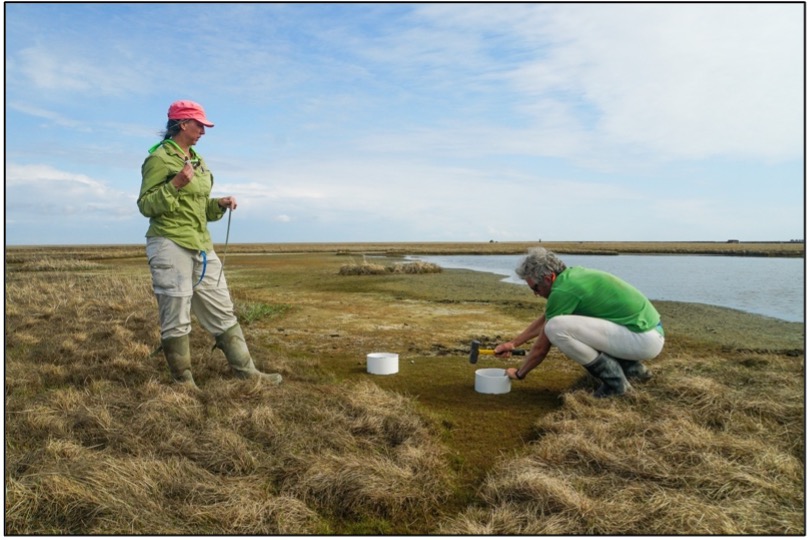

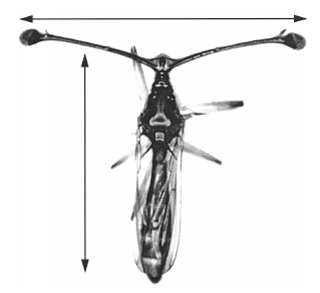

The SSE T. H. Huxley Award Committee has announced the winner of the 2025 T. H. Huxley Award, Dr. Elizabeth Schultheis, Education and Outreach Coordinator for the Kellogg Biological Station Long-Term Ecological Research Program at Michigan State University, for her collection of educational resources called “Data Nuggets”. Data Nuggets, which are developed in collaboration with Dr. Melissa Kjelvik, bring real data and scientific role models into the classroom to build quantitative and critical thinking skills.

As part of the award, Dr. Schultheis will receive funding to present her work at the National Association of Biology Teachers (NABT) conference in October.

The T. H. Huxley Award is administered by the T. H. Huxley Award Committee, a subset of the SSE Education and Outreach Committee.