The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

- Excel Sheet with Data and Graphs

- Grading Rubric

Nitrogen is the most abundant element in our atmosphere. All living things need nitrogen to live and grow, but plants and animals can’t use the atmospheric form. Instead, many plants extract nitrogen from the soil and in the case of crops, we supply nitrogen through fertilizer, in a form called nitrate.

Nitrate dissolves well in water. This helps make it easy for plants to use, but it can also end up in rivers and groundwater. Groundwater with just 10 milligrams of nitrate per liter is not safe to drink because it can lead to a higher risk of cancer and birth defects. It is really expensive to remove nitrate from drinking water. Towns whose groundwater is contaminated must either pay to remove it or find a new drinking water source. Virtually all nitrate pollution comes from fertilizers used on crops, so one way to address this problem is to change the way we farm.

Annual plants live for just one season and typically have smaller shallower root systems than perennial plants, which live for multiple seasons. Most farmland grows annuals like corn and soybeans, but we get some of our food from perennials like apples, hazelnuts, and raspberries. Perennials stay in the ground all year and start growing right away in the spring before annual crops are even planted. Perennial grasses are particularly good at growing deep roots and taking up lots of nitrate from the soil. If we could produce more food from perennial plants instead of annual plants, crops may absorb enough nitrate to prevent it from getting into our drinking water.

For twenty years, researchers at The Land Institute in Kansas and at the University of Minnesota have been working on a new perennial grain crop called Kernza®, the seeds from a plant called intermediate wheatgrass. Kernza® can be used like wheat or rye, but it has a larger, deeper root system than regular annual wheat. Perennial plants’ deep roots are really good at absorbing dissolved nitrate in soil, so scientists wanted to study Kernza® in the field to see if it would prevent nitrate getting into groundwater.

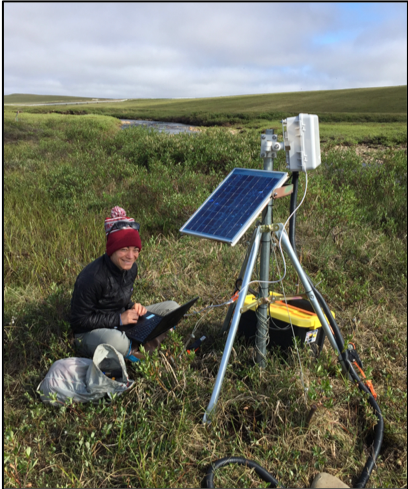

Evelyn is one of these researchers. She grew up in Minneapolis, Minnesota and as a high school student, she was surprised to learn that agriculture has a huge impact on soil and water quality, wildlife habitat, and biodiversity. She wanted to help protect the environment, so she studied Food Systems at the University of Minnesota. A few years later, she joined a project that involved planting Kernza® in rural areas to prevent and reduce nitrate contamination of drinking water. Farmers, city officials, water managers, and scientists worked together to find solutions. This project inspired Evelyn to study Kernza® and nitrate for her master’s degree.

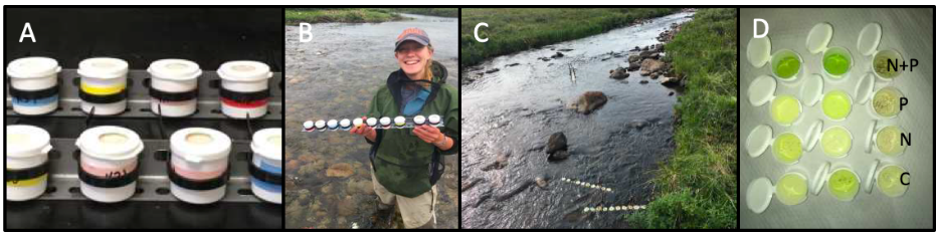

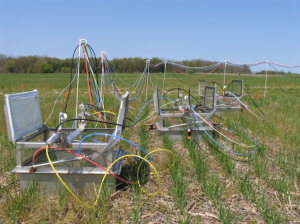

To see if Kernza® helped absorb more nitrate from soil than annual crops, Evelyn and her colleagues ran an experiment. They planted plots of Kernza® and other plots that rotated between corn and soybean every year. Plots with Kernza® and corn were fertilized with nitrogen. Soybean plots were not fertilized.

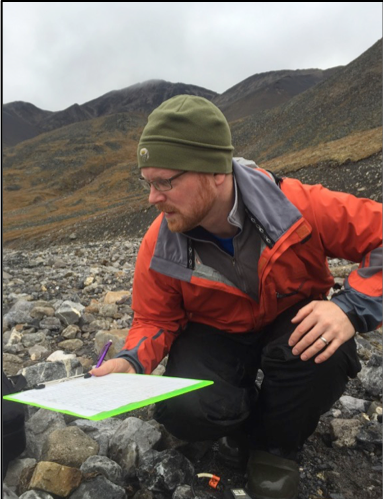

In the plots, they installed lysimeters: long tubes that go down several feet to collect soil water from below where most plant roots can reach it. Soil water is the water that sits between soil particles. It can be taken up by plant roots or trickle down into the groundwater that is used for drinking wells. Once it moves deeper than a plant’s roots, it can’t be taken up and is very likely to reach the groundwater. Evelyn took water samples from the lysimeters every ten days and analyzed them for nitrate concentration. If more nitrate is found in soil water under corn and soybean plots than Kernza®, this would be good evidence that Kernza® takes up more nitrate and helps protect groundwater.

Featured scientist: Evelyn Reilly (she/her) from University of Minnesota