Doug with the reciprocal transplant experiment in Scandinavia.

The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 4

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 4

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 4

- Grading Rubric

Doug is a biologist who studies plants from around the world. He often jokes that he chose to work with plants because he likes to take it easy. While animals rarely stay in the same place and are hard to catch, plants stay put and are always growing exactly where you planted them! Using plants allows Doug to do some pretty cool and challenging experiments. Doug and his research team carry out experiments with the plant species Mouse-ear Cress, or Arabidopsis thaliana. They like this species because it is easy to grow in both the lab and field. Arabidopsis is very small and lives for just one year. It grows across most of the globe across a wide range of latitudes and climates. Arabidopsis is also able to pollinate itself and produce many seeds, making it possible for researchers to grow many individuals to use in their experiments.

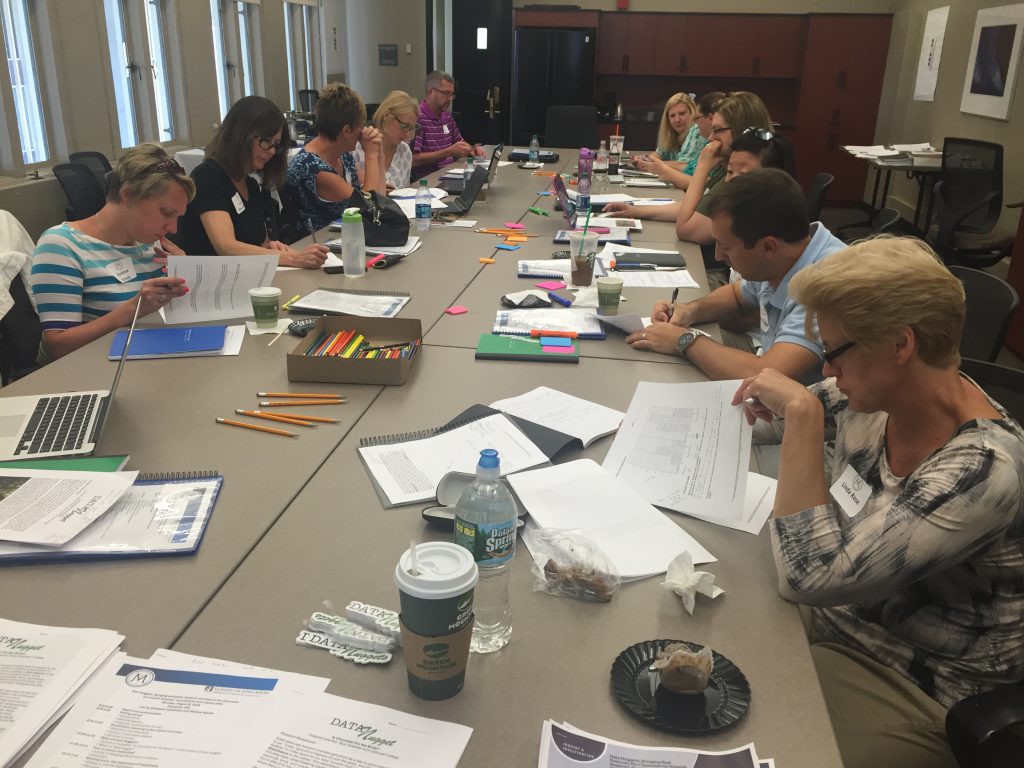

Doug, and two members of his team, setting up the reciprocal transplant experiment in Scandinavia.

Part I: Doug wanted to study how Arabidopsis is able to survive in such a range of climates. Depending on where they live, each population faces its own challenges. For example, there are some populations of this species growing in very cold habitats, and some populations growing in very warm habitats. He thought that each of these populations would adapt to their local environments. An Arabidopsis population growing in cold temperatures for many generations may evolve traits that increase survival and reproduction in cold temperatures. However, a population that lives in warm temperatures would not normally be exposed to cold temperatures, so the plants from that population would not be able to adapt to cold temperatures. The idea that populations of the same species have evolved as a result of certain aspects of their environment is called local adaptation.

To test whether Arabidopsis is locally adapted to its environment, Doug established a reciprocal transplant experiment. In this type of experiment, scientists collect seeds from plants in two different locations and then plant them back into the same location (home) and the other location (away). For example, seeds from population A would be planted back into location A (home), but also planted into location B (away). Seeds from population B would be planted back into location B (home), but also planted at location A (away). If populations A and B are locally adapted, this means that A will survive better than B in location A, and B will survive better than A in location B. Because each population would be adapted to the conditions from their original location, they would outperform the plants from away when they are at home (“home team advantage”).

In this experiment, Doug collected many seeds from warm Mediterranean locations at low latitudes, and cold Scandinavian locations at high latitudes. He used these seeds to grow thousands of seedlings. Once these young plants were big enough, they were planted into a reciprocal transplant experiment. Seedlings from the Mediterranean location were planted alongside Scandinavian seedlings in a field plot in Scandinavia. Similarly, seedlings from the Scandinavian locations were planted alongside Mediterranean seedlings in a field plot in the Mediterranean. By planting both Mediterranean and Scandinavian seedlings in each field plot, Doug can compare the relative survival of each population in each location. Doug made two local adaptation predictions:

- Scandinavian seedlings would survive better than Mediterranean seedlings at the Scandinavian field plot.

- Mediterranean seedlings would survive better than Scandinavian seedlings planted at the Mediterranean field plot.

Doug’s team in the Mediterranean prepped and ready to set up the experiment.

Part II: The data from Doug’s reciprocal transplant experiment show that the Arabidopsis populations are locally adapted to their home locations. Now that Doug confirmed that populations were locally adapted, he wanted to know how it happened. What is different about the two habitats? What traits of Arabidopsis are different between these two populations? Doug now wanted to figure out the mechanism causing the patterns he observed.

Doug originally chose Arabidopsis populations in Scandinavia and the Mediterranean for his research on local adaptation because those two locations have very different climates. The populations may have adapted to have the highest survival and reproduction based on the climate of their home location. To deal with sudden freezes and cold winters in Scandinavia, plants may have adaptations to help them cope. Some plants are able to protect themselves from freezing temperatures by producing chemicals that act like antifreeze. These chemicals accumulate in their tissues to keep the water from turning into ice and forming crystals. Doug thought that the Scandinavian population might have evolved traits that would allow the plants to survive the colder conditions. However, the plants from the Mediterranean aren’t normally exposed to cold temperatures, so they wouldn’t have necessarily evolved freeze tolerance traits.

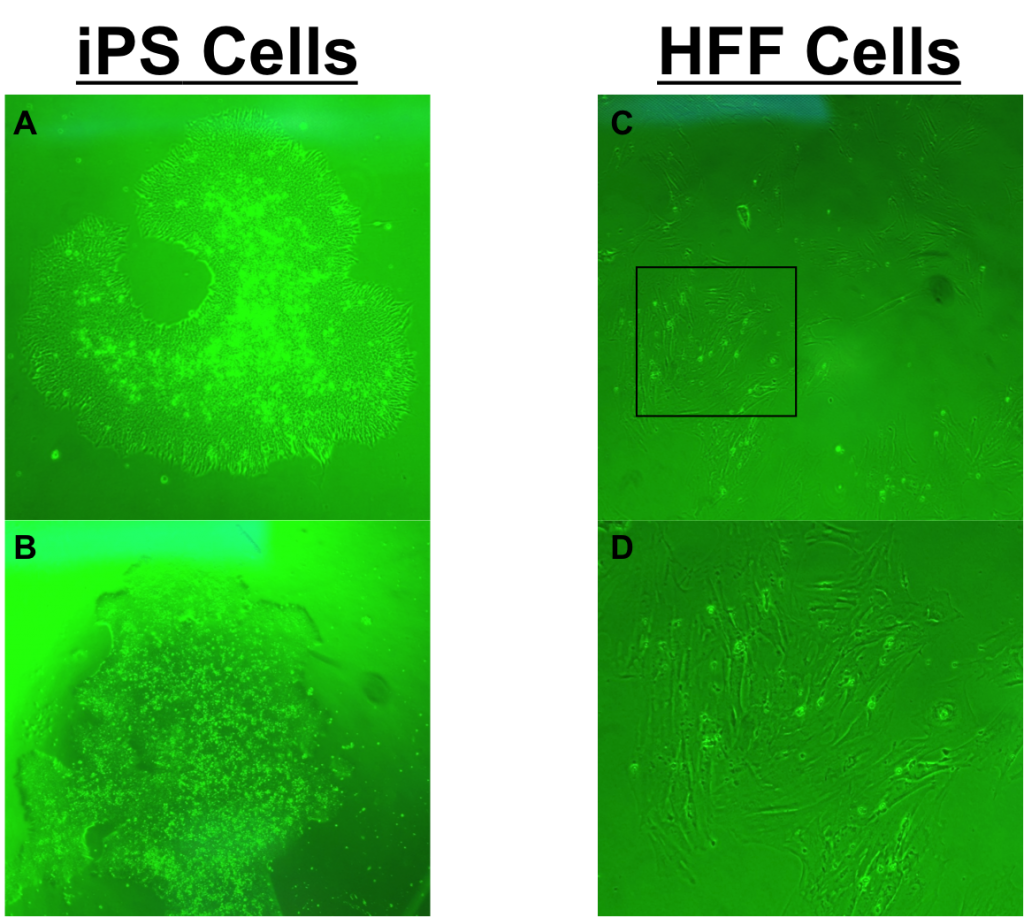

To see whether freeze tolerance was driving local adaptation, he set up an experiment to identify which plants survived after freezing. Doug again collected seeds from several different populations across Scandinavia and across the Mediterranean. He chose locations that had different latitudes because latitude affects how cold an area gets over the year. High latitudes (closer to the poles) are generally colder and low latitudes (closer to the equator) are generally warmer. Doug grew more seedlings for this experiment, and then, when they were a few days old, he put them in a freezer. Doug counted how many seedlings froze to death, and how many survived, and he used these numbers to calculate the percent survival for each population. To gain confidence in his results, he did this experiment with three replicate genotypes per population.

Doug predicted that if freeze tolerance was a trait driving local adaptation, the seedlings originally from colder latitudes (Scandinavia) would have increased survival after the freeze. Seedlings originally from lower latitudes would have decreased survival after the freeze because the populations would not have evolved tolerance to such cold temperatures.

Featured scientist: Doug Schemske from Michigan State University (MSU). Written by Christopher Oakley from MSU and Purdue University, and Marty Buehler (RET) from Hastings High School.

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 12.0

There is one scientific paper associated with the data in this Data Nugget. The citation and PDF of the paper is below.

Agren, J. and D.W. Schemske (2012). Reciprocal transplants demonstrate strong adaptive differentiation of the model organism Arabidopsis thaliana in its native range. New Phytologist 194:1112–1122.

About Tina: I first became interested in science catching frogs and snakes in my backyard in Ithaca, NY. This inspired me to major in Biology at Cornell University, located in my hometown. As an undergraduate, I studied male competition and sperm allocation in the local spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. After graduating, I joined the Peace Corps and spent 2 years in Morocco teaching environmental education and 6 months in Liberia teaching high school chemistry. As a PhD student in the Buston Lab, I study how parents negotiate over parental care in my study system the clownfish, Amphiprion percula, otherwise known as Nemo.

About Tina: I first became interested in science catching frogs and snakes in my backyard in Ithaca, NY. This inspired me to major in Biology at Cornell University, located in my hometown. As an undergraduate, I studied male competition and sperm allocation in the local spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. After graduating, I joined the Peace Corps and spent 2 years in Morocco teaching environmental education and 6 months in Liberia teaching high school chemistry. As a PhD student in the Buston Lab, I study how parents negotiate over parental care in my study system the clownfish, Amphiprion percula, otherwise known as Nemo.

The activities are as follows:

The activities are as follows:

About Erin: I am fascinated by morphological diversity, and my research aims to understand the selective pressures that drive (and constrain) the evolution of animal form. Competition for mates is a particularly strong evolutionary force, and my research focuses on how sexual selection has contributed to the elaborate and diverse morphologies found throughout the animal kingdom. Using horned beetles as a model system, I am interested in how male-male competition has driven the evolution of diverse weapon morphologies, and how sexual selection has shaped the evolution of physical performance capabilities. I am first and foremost a behavioral ecologist, but my research integrates many disciplines, including functional morphology, physiology, biomechanics, ecology, and evolution.

About Erin: I am fascinated by morphological diversity, and my research aims to understand the selective pressures that drive (and constrain) the evolution of animal form. Competition for mates is a particularly strong evolutionary force, and my research focuses on how sexual selection has contributed to the elaborate and diverse morphologies found throughout the animal kingdom. Using horned beetles as a model system, I am interested in how male-male competition has driven the evolution of diverse weapon morphologies, and how sexual selection has shaped the evolution of physical performance capabilities. I am first and foremost a behavioral ecologist, but my research integrates many disciplines, including functional morphology, physiology, biomechanics, ecology, and evolution.