Mountain chickadee, photo by Vladimir Pravosudov

The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 4

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 4

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 4

- Grading Rubric

Depending on where they live, animals can face a variety of challenges from the environment. For example, animal species that live in cold environments may have adaptive traits that help them survive and reproduce under those conditions, such as thick fur or a layer of blubber. Animals may also have adaptive behaviors that help them deal with the environment, such as storing food for periods when it is scarce or hibernating during times of the year when living conditions are most unfavorable. These adaptations are usually consistently seen in all individuals within a species. However, sometimes populations of the same species may be exposed to different conditions depending on where they live. The idea that populations of the same species have evolved as a result of certain aspects of their environment is called local adaptation.

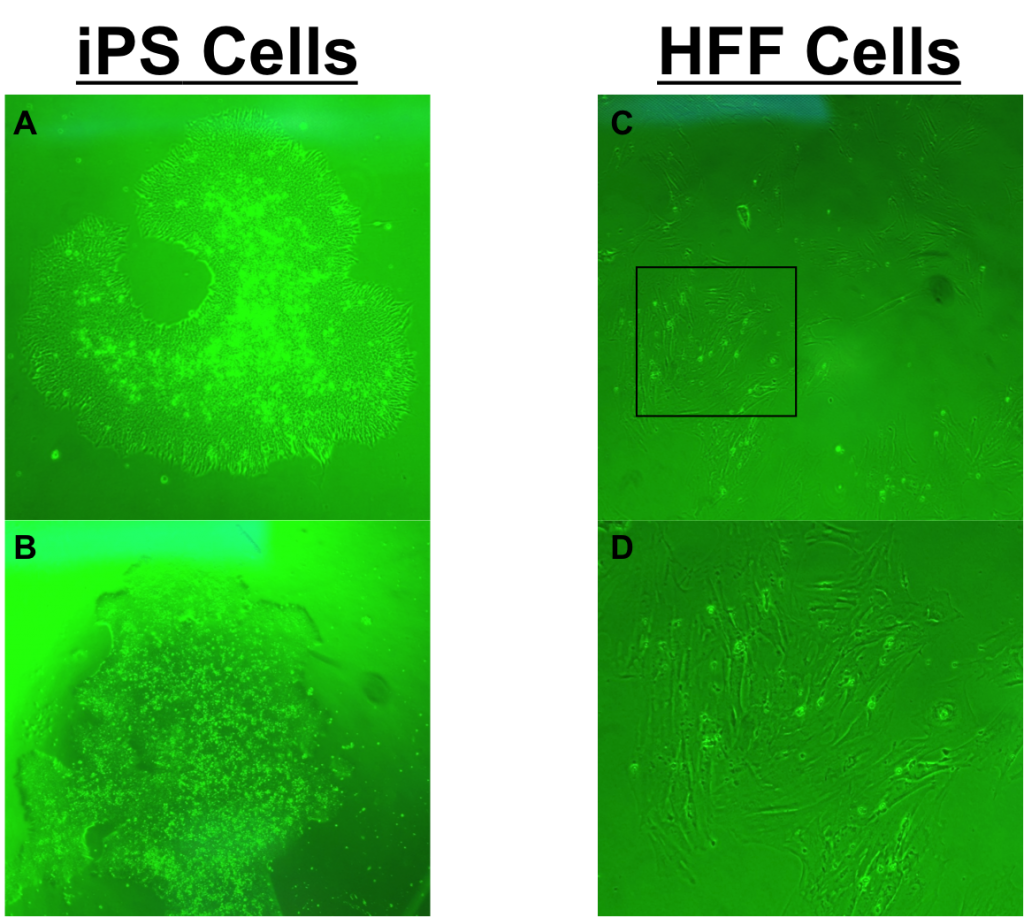

Mountain chickadees are small birds that live in the mountains of western North America. These birds do not migrate to warmer locations like many other bird species; they remain in the same location all year long. To deal with living in a harsh environment during the winter, mountain chickadees store large amounts of food throughout the forest during the summer and fall. They eat this food in the winter when very little fresh food is available. There are some populations of the species that live near the tops of mountains, and some that live at lower elevations. Birds at higher elevations experience harsher winter conditions (lower temperature, more snow) compared to birds living at lower elevations. This means that birds higher in the mountains depend more on their stored food to survive winter.

Carrie conducting field research in winter, photo by Vladimir Pravosudov

Carrie studies mountain chickadees in California. Based on previous research that was done in the lab she works in, she learned these birds have excellent spatial memory, or the ability to recall locations or navigate back to a particular place. This type of memory makes it easier for the mountain chickadees to find the food they stored. Carrie’s lab colleagues previously found that populations of birds from high elevations have much better spatial memory compared to low-elevation birds. Mountain chickadees also display aggressive behaviors and fight to defend resources including territories, food, or mates. Previous work that Carrie and her lab mate conducted found that male birds from low elevations are socially dominant over male birds from high elevations, meaning they are more likely to win in a fight over resources. Taken together, these studies suggest that birds from high elevations would likely do poorly at low elevations due to their lower dominance status, but low-elevation birds would likely do poorly at high elevations with harsher winter conditions due to their inferior memory for finding stored food items. These populations of birds are likely locally adapted – individuals from either population would likely be more successful in their own environments compared to the other.

In this species, females choose which males they will mate with. Males from the same elevation as the females may be best adapted to the location where the female lives. This means that when the female lays her eggs, her offspring will likely inherit traits that are well suited for that environment. If she mates with males that match her environment, she is setting up her offspring to be more successful and have higher survival where they will live. Carrie wondered if female mountain chickadees prefer to mate with males that are from the same elevation and therefor contribute to local adaptation by passing the adaptive behaviors on to the offspring. This process could contribute to the populations becoming more and more distinct. Offspring born in the high mountains will continue to inherit genes for good spatial memory, and those born at low elevations will inherit genes that allow them to be socially dominant.

Mountain chickadee, photo by Vladimir Pravosudov

To test whether female mountain chickadees contribute to local adaptation by choosing and mating with males from their own elevation, Carrie brought high- and low-elevation males and females into the lab. Carrie made sure that the conditions in the lab were similar to the light conditions in the spring when the birds mate (14 hours of light, 10 hours of dark). Once a female was ready, she was given time to spend with both males in a cage that is called a two-choice testing chamber. On one side of the testing chamber was a male from a low-elevation population, and on the other side was a male from a high-elevation population. Each female could fly between the two sides of the testing chamber, allowing her to “choose” which male she preferred to spend time close to (measured in seconds [s]). There was a cardboard divider in the middle of the cage with a small hole cut into it. This allowed the female to sit on the middle of the cardboard, which was not counted as preference for either male. Females from both high- and low-elevation populations were tested in the same way. The female bird’s preference was determined by comparing the amount of time the female spent on either side of the cage. The more time a female spent on the side of the cage near one male, the stronger her preference for that male.

Watch a video of one of the experimental trials:

Featured scientist: Carrie Branch from University of Nevada Reno

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 11.5

Additional teacher resources related to this Data Nugget include:

- Carrie’s lab’s website, for more information on chickadee cognition!

- A YouTube video of one of Carrie’s experimental trials showing a female in the two-choice testing chamber. Students can observe the female chickadee as she decides between the males on her left or the one on her right.

- The paper published using these data and testing alternative hypotheses:

- Branch, C.L., Kozlovsky, D.Y., and V.V. Pravosudoc. 2015. Elevation-related differences in female mate preferences in mountain chickadees: are smart chickadees choosier? Animal Behavior 99: 89-94.

About Carrie: I have been interested in animal behavior and behavioral ecology since my second year in college at the University of Tennessee. I am primarily interested in how variation in ecology and environment affect communication and signaling in birds. I have also studied various types of memory and am interested in how animals learn and use information depending on how their environment varies over space and time. I am currently working on my PhD in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology at the University of Nevada Reno and once I finish I hope to become a professor at a university so that I can continue to conduct research and teach students about animal behavior. In my spare time I love hiking with my friends and dogs, and watching comedies!

About Carrie: I have been interested in animal behavior and behavioral ecology since my second year in college at the University of Tennessee. I am primarily interested in how variation in ecology and environment affect communication and signaling in birds. I have also studied various types of memory and am interested in how animals learn and use information depending on how their environment varies over space and time. I am currently working on my PhD in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology at the University of Nevada Reno and once I finish I hope to become a professor at a university so that I can continue to conduct research and teach students about animal behavior. In my spare time I love hiking with my friends and dogs, and watching comedies!

About Tina: I first became interested in science catching frogs and snakes in my backyard in Ithaca, NY. This inspired me to major in Biology at Cornell University, located in my hometown. As an undergraduate, I studied male competition and sperm allocation in the local spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. After graduating, I joined the Peace Corps and spent 2 years in Morocco teaching environmental education and 6 months in Liberia teaching high school chemistry. As a PhD student in the Buston Lab, I study how parents negotiate over parental care in my study system the clownfish, Amphiprion percula, otherwise known as Nemo.

About Tina: I first became interested in science catching frogs and snakes in my backyard in Ithaca, NY. This inspired me to major in Biology at Cornell University, located in my hometown. As an undergraduate, I studied male competition and sperm allocation in the local spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. After graduating, I joined the Peace Corps and spent 2 years in Morocco teaching environmental education and 6 months in Liberia teaching high school chemistry. As a PhD student in the Buston Lab, I study how parents negotiate over parental care in my study system the clownfish, Amphiprion percula, otherwise known as Nemo.  The activities are as follows:

The activities are as follows:

About Erin: I am fascinated by morphological diversity, and my research aims to understand the selective pressures that drive (and constrain) the evolution of animal form. Competition for mates is a particularly strong evolutionary force, and my research focuses on how sexual selection has contributed to the elaborate and diverse morphologies found throughout the animal kingdom. Using horned beetles as a model system, I am interested in how male-male competition has driven the evolution of diverse weapon morphologies, and how sexual selection has shaped the evolution of physical performance capabilities. I am first and foremost a behavioral ecologist, but my research integrates many disciplines, including functional morphology, physiology, biomechanics, ecology, and evolution.

About Erin: I am fascinated by morphological diversity, and my research aims to understand the selective pressures that drive (and constrain) the evolution of animal form. Competition for mates is a particularly strong evolutionary force, and my research focuses on how sexual selection has contributed to the elaborate and diverse morphologies found throughout the animal kingdom. Using horned beetles as a model system, I am interested in how male-male competition has driven the evolution of diverse weapon morphologies, and how sexual selection has shaped the evolution of physical performance capabilities. I am first and foremost a behavioral ecologist, but my research integrates many disciplines, including functional morphology, physiology, biomechanics, ecology, and evolution.