The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

- Grading Rubric

Throughout history people have settled mainly along rivers and streams. Easy access to water provides resources to support many people living in one area. In the United States today, people have settled along 70% of rivers.

Today, rivers are very different from what they were like before people settled near them. The land surrounding these rivers, called riparian habitats, has been transformed into land for farming, businesses, or housing for people. This urbanization has caused the loss of green spaces that provide valuable services, such as water filtration, species diversity, and a connection to nature for people living in cities. Today, people are trying to restore green spaces along the river to bring back these services. Restoration of disturbed riparian habitats will hopefully bring back native species and all the other benefits these habitats provide.

Scientists Heather and Mélanie are researchers with the Central Arizona-Phoenix Long-Term Ecological Research (CAP LTER) project. They want to know how restoration will affect animals living near rivers. They are particularly interested in reptiles, such as lizards. Reptiles play important roles in riparian habitats. Reptiles help energy flow and nutrient cycling. This means that if reptiles live in restored riparian habitats, they could increase the long-term health of those habitats. Reptiles can also offer clues about the condition of an ecosystem. Areas where reptiles are found are usually in better condition than areas where reptiles do not live.

Heather and Mélanie wanted to look at how disturbances in riparian habitats affected reptiles. They wanted to know if reptile abundance (number of individuals) and diversity (number of species) would be different in areas that were more developed. Some reptile species may be sensitive to urbanization, but if these habitats are restored their diversity and abundance might increase or return to pre-urbanization levels. The scientists collected data along the Salt River in Arizona. They had three sites: 1) a non-urban site, 2) an urban disturbed site, and 3) an urban rehabilitated site. They counted reptiles that they saw during a survey. At each site, they searched 21 plots that were 10 meters wide and 20 meters long. The sites were located along 7 transects, or paths measured out to collect data. Transects were laid out along the riparian habitat of the stream and there were 3 plots per transect. Each plot was surveyed 5 times. They searched for animals on the ground, under rocks, and in trees and shrubs.

Featured scientists: Heather Bateman and Mélanie Banville from Arizona State University. Written by Monica Elser from Arizona State University.

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 9.8

Check out this video of Heather and her lab out in the field collecting lizards:

Virtual field trip to the Salt River biodiversity project:

Additional resources related to this Data Nugget:

- For more background on the importance of biodiversity, students can eat this article in The Guardian – What is biodiversity and why does it matter to us?

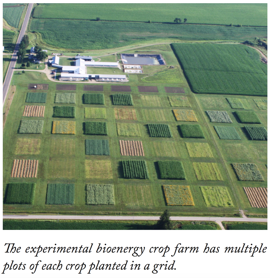

This Data Nugget was adapted from a data analysis activity developed by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC). For a more detailed version of this lesson plan, including a supplemental reading, biomass harvest video and extension activities,

This Data Nugget was adapted from a data analysis activity developed by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC). For a more detailed version of this lesson plan, including a supplemental reading, biomass harvest video and extension activities,

About Skye: As a child Skye was always asking why; questioning the behavior, characteristics, and interactions of plants and animals around her. She spent her childhood reconstructing deer skeletons to understand how bones and joints functioned and creating endless mini-ecosystems in plastic bottles to watch how they changed over time. This love of discovery, observation, questioning, and experimentation led her to many technician jobs, independent research projects, and graduate research study at Purdue University. At Purdue she studies the factors influencing oak regeneration after ecologically based timber harvest and prescribed fire. While Skye’s primary focus is ecological research, she loves getting to leave the lab and bring science into classrooms to inspire the next generation of young scientists and encourage all students to be always asking why!

About Skye: As a child Skye was always asking why; questioning the behavior, characteristics, and interactions of plants and animals around her. She spent her childhood reconstructing deer skeletons to understand how bones and joints functioned and creating endless mini-ecosystems in plastic bottles to watch how they changed over time. This love of discovery, observation, questioning, and experimentation led her to many technician jobs, independent research projects, and graduate research study at Purdue University. At Purdue she studies the factors influencing oak regeneration after ecologically based timber harvest and prescribed fire. While Skye’s primary focus is ecological research, she loves getting to leave the lab and bring science into classrooms to inspire the next generation of young scientists and encourage all students to be always asking why!