The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

- Grading Rubric

As the climate changes, Michigan is expected to experience more drought. Droughts are periods of low rainfall when water becomes limiting to organisms. This is a challenge for our agricultural food system. Farmers in Michigan will be planting crops into conditions that make it harder for corn, soybean, and wheat to grow and survive.

Scientists are looking into how crop interactions with other organisms may help. Microbes are microscopic organisms that live in soils everywhere. Some microbes can help crops get through time times. These beneficial microbes are called mutualists. They give plants nutrients and water in exchange for carbon from the plant. Microbes use the carbon they get from plants as food. If plants are stressed and don’t have any carbon to give, microbes get carbon from dead plant material in the soil.

Jennifer is a biologist studying the role of microbes in agriculture. She has always been interested in a career that would help people. As a student, Jennifer thought she would have a career in politics. Along the way, she learned that a career in science is a great way to study questions that may lead to solutions for the challenges we are facing today. Jennifer was drawn to the Kellogg Biological Station, where she joined a team of scientists studying the impacts of climate change and drought on agriculture.

Jennifer and other scientists set out to test ways that we can give mutualists in the soil a boost. She thought, perhaps if we were to give microbes more food, they would be less stressed during a drought and would be able to help out crops growing in these stressful conditions.

To test this idea, Jennifer needed to test how well microbes were doing under different carbon and drought conditions. First, she set up treatments in soybean fields to manipulate the amount of carbon in the soil. She set up control plots where she left the soil alone. She also set up carbon treatment plots where dead plant litter was added to the soil to increase the carbon available to microbes.

Next, Jennifer manipulated the availability of water in her plots to test the microbes under stress. To do this, she set up her plots under shelters that kept out rain. The shelters had sprinklers, which were automated to add specific amounts of water to the plots. This design allowed Jennifer to control the watering schedule for each plot. One shelter treatment was a control, where water was added to the plots every week. This is similar to the schedules of local farmers who add water through irrigation. The other shelter treatment was drought, where plots received no water for six weeks. This experiment was replicated 4 times, meaning there were 4 shelters on the control watering schedule and 4 shelters that were under drought conditions.

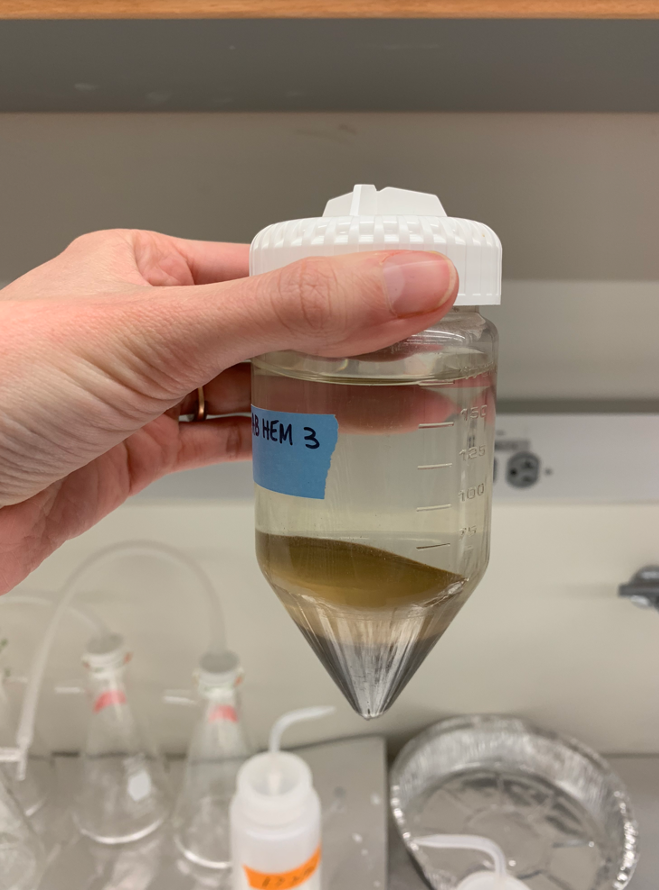

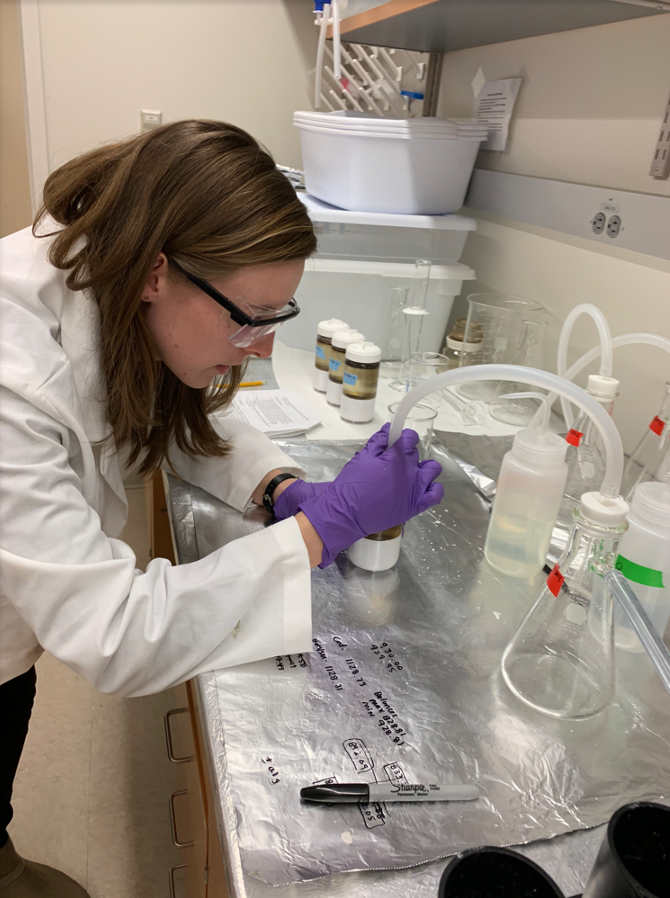

Finally, Jennifer had to measure how the microbes were doing in each treatment. She did this by measuring their enzyme activity. Enzyme activity is a measure of how active the microbes are. The higher the enzyme activity, the happier the microbes are. To measure this, Jennifer collected soil samples from each plot throughout the growing season and took them to the lab to measure enzyme levels in the soil samples. These enzymes are made by microbes when they are active. She then calculated the mean of all her samples for each treatment combination.

Jennifer predicted two things. First, if drought is harmful to microbes, then she would expect to see lower enzyme activity in the drought treatment compared to the irrigated treatment. Second, if adding carbon to the soil is a way to help microbes overcome the challenge of drought, she expected higher enzyme activity in the plots with plant litter added compared to the control treatment. Both of these taken together would indicate that drought is stressful for microbes, but we can help them out by adding resources like plant litter to soils.

Featured scientist: Jennifer Jones (she/her) from the Kellogg Biological Station Long Term Ecological Research Site. Written with Melissa Frost and Liz Schultheis.

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 8.2

Additional teacher resources related to this Data Nugget:

To introduce this Data Nuggets activity, students can watch a talk by Jennifer when she made a classroom visit to share her background and research interests. This video is a great way to introduce students to scientist role models and learn more about what a career in science looks like, as well as get an introduction to the themes in the research.

There is also a video of Jennifer and her scientist colleague, Grant Falvo, out in the field talking about their research under the rainout shelters.

For more information about the rainout shelter experiment, students can watch this short video featuring Jennifer Jones and another scientist on the team, Grant Falvo:

These data are part of the Kellogg Biological Station Long Term Ecological Research Program (KBS LTER). To learn more about the KBS LTER, visit their website.