Below, you will find a table of the 26 Data Nuggets to be used in the research study. Click on the Title to open a page displaying the Data Nugget and associated activities. The table can be sorted using the arrows located next to each column header. It can also be searched using the search command at the top of the table. By default we have the activities sorted by increasing difficulty.

For a reminder on what the Content Levels (1-4) and Graph Types (A-C) mean, check out our information page here.

| Title | Content Level | Keywords | Summary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Won’t you be my urchin? | 1 | coral reef, herbivory, marine, sea urchin, water, animals, competition | Corals are the most important reef animals since they build the reef for all of the other animals to live in. But corals only like to live in certain places. In particular they hate living near algae because the algae and coral compete for the space they both need to grow. Perhaps if there are more vegetarians, like urchins, eating algae on the reef then corals would have less competition and more space to grow. |

| Coral bleaching and climate change | 1 | climate change, coral reef, marine, mutualism, temperature, animals, algae | Corals are animals that build coral reefs. They look brown and green because they have small plants, called algae, that live inside them. The coral animal and the algae work together to produce food so that corals can grow big. When the water gets too warm, sometimes the coral and algae can no longer work together. The algae leave and the corals turn white, called coral bleaching. Scientists want to study coral bleaching so they can protect corals and the reefs that provide a home for so many different species. |

| Dangerously bold | 1 | animals, animal behavior, tradeoff, fish, predation | There are two main habitats that young bluegill sunfish can use to find food to eat – open water and cover. There is lots of food in the open water, but this habitat also has very few plants for bluegill to hide from predators, like the largemouth bass, so it’s not safe when bluegill are small! The cover habitat has less food, but it has lots of plants that make it hard for predators to see the bluegill. This sets up a situation where there are costs and benefits to using either habitat, called a tradeoff. |

| Springing forward | 1 & 3 | climate change, phenology, plants, temperature | What does climate change mean for flowering plants that rely on temperature cues to determine when it is time to flower? Scientists who study phenology, or the timing if life-history events in plants and animals, predict that with warming temperatures, plants will produce their flowers earlier and earlier each year. |

| Do insects prefer local or foreign foods? | 2 | herbivory, invasive species, plants, insects, enemy release, ecology | Insects that feed on plants, called herbivores, can have big effects on how plants grow. A plant with leaves eaten by herbivores will likely do worse than a plant that is not eaten. Herbivores may even determine how well an exotic plant does in its new habitat and whether it becomes invasive. Understanding what makes a species become invasive could help control invasions already underway, and prevent new ones in the future. |

| Deadly windows | 2 | animals, behavior, birds, environmental | Glass makes for a great windowpane because you can see right through it. However, this makes windows very dangerous for birds. Many birds die from window collisions in urban areas. In North America window collisions kill up to 1 billion birds every year! Perhaps local urban birds are able to learn the locations of windows and avoid collisions. By comparing window collisions by local birds to those of migrant birds that are just passing through, we can determine if local birds have learned to deal with this challenge. |

| A tail of two scorpions | 2 | animal behavior, animals, predation | Species rely on a variety of methods to defend against predators, including camouflage, speedy escape, or retreating to the safety of a shelter. Other animals, such as scorpions, have painful venomous stings. Scientists wanted to know whether the pain of a scorpion sting was enough to deter predators, like the grasshopper mouse. |

| Sexy smells | 2 | adaptation, animal behavior, animals, birds, mating | Animals collect information about each other and the rest of the world using multiple senses, including sight, sound, and smell. They use this information to decide what to eat, where to live, and who to pick as a mate. Many male birds have brightly colored feathers and ornaments that are attractive to females. Visual signals like these ornaments have been studied a lot in birds, but birds may be able to determine the quality of a potential mate using other senses as well, such as their smell! |

| How do brain chemicals influence who wins a fight? | 2 | animals, behavior, competition, insects, aggression, brain chemistry, physiology | Animals compete for resources, including space, food, and mates. What are the factors that determine who wins in a fight? Within the same species, larger individuals tend to win fights. However, if two opponents are the same size, other factors can influence outcomes. Serotonin is a chemical compound found in the brains of all animals, including stalk-eyed flies. Even a small amount of this chemical can make a big impact on aggressive behavior, and perhaps the outcome of competition. |

| Marvelous mud | 2 | ecology, environmental, fertilization, mud, phosphorus, substrate, water, wetland | Because mud is wet most of the time, it tends to have different properties than soil. Dead organic matter (partially decomposed plants) is an important part of mud and tends to build up in wetlands because it is decomposed more slowly under water where microbes do not have all the oxygen they need to break it down quickly. The amounts of organic matter may determine the levels of phosphorus and other nutrients held in wetland muds. |

| Is chocolate for the birds? | 2 | agriculture, animals, birds, biodiversity, ecology, plants, rainforest | Humans invented agriculture 9,000 years ago, and today it covers 40% of Earth’s land surface. To grow our crops, native plants are often removed, causing the loss of animals that relied on these native plants for habitat. However, sometimes animals can use crop species for food and shelter. For example, the cacao tree may provide habitat for bird species in the rainforests of Costa Rica. Will the abundance and types of birds differ in cacao plantations, compared to native rainforests? |

| Bye bye birdie? Part I | 2 | animals, biodiversity, birds, climate change, succession, disturbance, ecology | Avian ecologists at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest have been monitoring bird populations for over 40 years. The data collected during this time is one of the longest bird studies ever conducted! What can we learn from this long-term data set? Are bird populations remaining stable over time? |

| Bye bye birdie? Part II | 3 | animals, biodiversity, birds, climate change, succession, disturbance, ecology | Hubbard Brook was heavily logged and disturbed in the early 1900s. When logging ended in 1915, trees began to grow back. The forest then went through secondary succession, which refers to the naturally occurring changes in forest structure that happen as a forest ages after it has been cut or otherwise disturbed. Can these changes in habitat availability, due to succession, explain why the number of birds are declining at Hubbard Brook? Are all bird species responding succession in the same way? |

| To bee or not to bee aggressive | 3 | animals, behavior, genes, insects, tradeoff | Honey bees turn nectar from flowers into honey, and honey serves as an energy-rich food source for the colony. Honey also makes hives a target for break ins by animals that want to steal it. Bees need to aggressively defend their honey when the hive is threatened. They also need to ensure that they do not waste energy on unnecessary aggressive behaviors when the threat level is low. One way bees might match their aggressiveness to the threat level in the environment is learning from adults when they are young. |

| Raising Nemo: Parental care in the clown anemonefish | 3 | adaptation, animals, behavior, coral reef, ecology, fish, marine, mating, tradeoff | Offspring in many animal species rely on parental care; the more time and energy parents invest in their young, the more likely it is that their offspring will survive. However, parental care is costly for the parents. The more time spent on care, the less time they have to find food or care for themselves. In the clown anemonefish, the amount of food available may impact parental care behaviors. When there is food freely available in the environment, are parents able to spend more time caring for their young? |

| Growing energy: comparing biofuel crop biomass | 3 | agriculture, biofuels, climate change, fertilization, plants | Corn is one of the best crops for producing biomass for fossil fuels, however it is an annual and needs very fertile soil. To grow corn, farmers add a lot of chemical fertilizers and pesticides to their fields. Other crops, like switchgrass, prairie, poplar trees, and Miscanthus grass are perennials and require fewer fertilizers and pesticides to grow. If perennials can produce high levels of biomass with low inputs, perhaps they could produce more biomass than corn under certain low nutrient conditions. |

| Fertilizing biofuels may cause release of greenhouse gasses | 3 | biofuels, climate change, fertilization, greenhouse gasses, nitrogen, plants | One way to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases we release into the atmosphere could be to grow our fuel instead of drilling for it. Unlike fossil fuels that can only release CO2, biofuels remove CO2 from the atmosphere as they grow and photosynthesize, potentially balancing the CO2 released when they are burned for fuel. However, the plants we grow for biofuels don’t necessarily absorb all greenhouse gas that is released during the process of growing them on farms and converting them into fuels. |

| The ground has gas! | 3 | climate change, temperature, greenhouse gasses, nitrogen, plants | Nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide are responsible for much of the warming of the global average temperature that is causing climate change. Sometimes soils give off, or emit, these greenhouse gases into the earth’s atmosphere, adding to climate change. Currently scientists figuring out what causes differences in how much of each type of greenhouse gas soils emit. |

| When a species can’t stand the heat | 3 | animals, climate change, disturbance, ecology, environmental, mating, temperature | Tuatara are a unique species of reptile found only in New Zealand. In this species, the temperature of the nest during egg development determines the sex of offspring. Warm nests lead to more males, and cool nests lead to more females. With warming temperatures due to climate change, scientists expect the sex ratio to become more and more unbalanced over time, with males making up more of the population. This could leave tuatara populations with too few females to sustain their numbers. |

| Feral chickens fly the coop | 3 | adaptation, animals, behavior, birds, ecology, evolution, mating | Sometimes domesticated animals escape captivity and interbreed with closely related wild relatives. Their hybrid offspring have some traits from the wild parent, and some from the domestic parent. Traits that help hybrids survive and reproduce will be favored by natural selection. On the island of Kauai, domestic chickens escaped and recently interbred with wild Red Junglefowl to produce a hybrid population. Over time, will the hybrids on Kauai evolve to be more like chickens, or more like Red Junglefowl? |

| CSI: Crime Solving Insects | 3 | animals, insects, parasitism | You might think maggots (blow fly larvae) are gross, but without their help in decomposition we would all trip over dead bodies every time we went outside! Forensic entomologists also use these amazing insects to help solve crimes. Blow flies oviposit on dead bodies, and the age of the maggots that hatch helps scientists determine how long ago a body died. Scientists noticed parasitic wasps were also present at some bodies. Might these wasps delay blow fly oviposition and interfere with scientists' estimates of time of death? |

| How the cricket lost its song, Part I | 3 | adaptation, animal behavior, animals, evolution, mating, parasitism | Pacific field crickets live on several Hawaiian Islands, including Kauai. Male field crickets make a loud, long-distance song to help females find them, and then switch to a quiet courtship song once a female comes in close. One summer scientists noticed that the crickets on the island were unusually quiet. Back in the lab they saw males that had lost their specialized wing structures used to produce song! Why did these males lose their wing structures? |

| How the cricket lost its song, Part II | 3 | adaptation, animal behavior, animals, evolution, mating, parasitism | WIthout their song, how are flatwing crickets able to attract females? In some other animals species, males use an alternative to singing, called satellite behavior. Satellite males hang out near a singing male and attempt to mate with females who have been attracted by the song. Perhaps the satellite behavior gives flatwing males the opportunity to mate with females who were attracted to the few singing males left on Kauai. |

| Are you my species? | 3 | adaptation, animals, behavior, biodiversity, competition, evolution, fish, mating | How do animals know who to choose as a mate and who is a member of their own species? One way is through communication. Animals collect information about each other and the rest of the world using multiple senses, including sight, sound, and smell. Darters are a group of over 200 colorful fish species that live in lakes and rivers across the US. The bright color patterns on males may signal to females during mating who is a member of the same species and who would make a good mate. |

| The mystery of Plum Island Marsh | 3 | fertilization, fish, marine, mollusk, water, wetland | Salt marshes are among the most productive coastal ecosystems, and support a diversity of plants and animals. Algae and marsh plants feed many invertebrates, like snails and crabs, which are then eaten by larger fish and birds. In Plum Island, scientists have been fertilizing and studying salt marsh creeks to see how added nutrients affect the system. They noticed that fish populations seemed to be crashing in the fertilized creeks, while the mudflats were covered in mudsnails. Could there be a link? |

| Finding Mr. Right | 4 | adaptation, animals, behavior, biodiversity, birds, evolution, mating, local adaptation | Mountain chickadees are small birds that live in the mountains. To deal with living in a harsh environment during the winter, mountain chickadees store large amounts of food throughout the forest. Compared to populations at lower elevations, birds from higher elevations are smarter and have better spatial memory, helping them better find stored food. Smarter females from high elevations may be contributing to local adaptation by preferring to breed with males from their own population. |

Below are links to all the materials from the research study, Scientific Data in Schools: Measuring the efficacy of an innovative approach to integrating quantitative reasoning in secondary science. If you have any questions, our contact information is linked below!

Below are links to all the materials from the research study, Scientific Data in Schools: Measuring the efficacy of an innovative approach to integrating quantitative reasoning in secondary science. If you have any questions, our contact information is linked below!

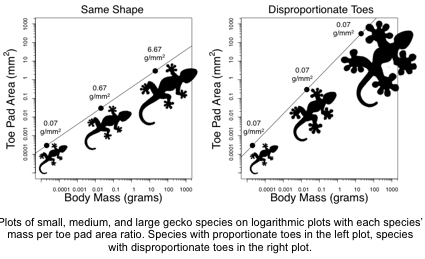

About Travis: Ever since Travis was a kid, he was interested in animals and wanted to be a paleontologist. He even had many dinosaur names memorized to back it up! In college he discovered evolutionary biology, which drove him to apply for graduate school and become a scientist. There, he fell in love with comparative biomechanics, which combines evolutionary biology and mechanical engineering. Today Travis studies geckos and their sticky toes that allow them to scale surfaces like glass windows and tree branches.

About Travis: Ever since Travis was a kid, he was interested in animals and wanted to be a paleontologist. He even had many dinosaur names memorized to back it up! In college he discovered evolutionary biology, which drove him to apply for graduate school and become a scientist. There, he fell in love with comparative biomechanics, which combines evolutionary biology and mechanical engineering. Today Travis studies geckos and their sticky toes that allow them to scale surfaces like glass windows and tree branches.

About Carrie: I have been interested in animal behavior and behavioral ecology since my second year in college at the University of Tennessee. I am primarily interested in how variation in ecology and environment affect communication and signaling in birds. I have also studied various types of memory and am interested in how animals learn and use information depending on how their environment varies over space and time. I am currently working on my PhD in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology at the University of Nevada Reno and once I finish I hope to become a professor at a university so that I can continue to conduct research and teach students about animal behavior. In my spare time I love hiking with my friends and dogs, and watching comedies!

About Carrie: I have been interested in animal behavior and behavioral ecology since my second year in college at the University of Tennessee. I am primarily interested in how variation in ecology and environment affect communication and signaling in birds. I have also studied various types of memory and am interested in how animals learn and use information depending on how their environment varies over space and time. I am currently working on my PhD in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology at the University of Nevada Reno and once I finish I hope to become a professor at a university so that I can continue to conduct research and teach students about animal behavior. In my spare time I love hiking with my friends and dogs, and watching comedies!

About Erin: I am fascinated by morphological diversity, and my research aims to understand the selective pressures that drive (and constrain) the evolution of animal form. Competition for mates is a particularly strong evolutionary force, and my research focuses on how sexual selection has contributed to the elaborate and diverse morphologies found throughout the animal kingdom. Using horned beetles as a model system, I am interested in how male-male competition has driven the evolution of diverse weapon morphologies, and how sexual selection has shaped the evolution of physical performance capabilities. I am first and foremost a behavioral ecologist, but my research integrates many disciplines, including functional morphology, physiology, biomechanics, ecology, and evolution.

About Erin: I am fascinated by morphological diversity, and my research aims to understand the selective pressures that drive (and constrain) the evolution of animal form. Competition for mates is a particularly strong evolutionary force, and my research focuses on how sexual selection has contributed to the elaborate and diverse morphologies found throughout the animal kingdom. Using horned beetles as a model system, I am interested in how male-male competition has driven the evolution of diverse weapon morphologies, and how sexual selection has shaped the evolution of physical performance capabilities. I am first and foremost a behavioral ecologist, but my research integrates many disciplines, including functional morphology, physiology, biomechanics, ecology, and evolution.