The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 4

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 4

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 4

- PowerPoint of images

- Scientist Profile on Project Biodiversify

- Scientist Profile

- Grading Rubric

Have you ever eaten an apple and noticed that, after a while, the core turns brown? That’s because of oxidation – a chemical reaction between the oxygen in the air and the inside of the apple. The same thing is happening inside our own bodies all the time.

Each of our cells is home to mitochondria, tiny factories whose job is to turn the food we eat into the energy we need to live. But mitochondria also make molecules called reactive oxygen species, or ROS. As the name suggests, these molecules contain oxygen and tend to react with the things around them. Like the oxygen in the air reacting with the apple core and turning it brown, ROS react with different parts of the cell, causing oxidative damage. Everything in the cell, including our DNA, can be damaged by ROS molecules. Too much damage contributes to diseases including cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and Parkinson’s.

Bodies can prevent oxidative damage in two ways. First, they can use antioxidants. Antioxidants work by reacting with ROS to stop them from harming cells. Some antioxidants come from the food we eat, while others are made inside the body. If a body doesn’t have enough antioxidants, it can get sick. One example is a genetic mutation called DJ-1. It stops the body from producing antioxidant molecules. Many people with Parkinson’s disease, a neurological illness, have this DJ-1 mutation.

Some living things have evolved a second way to stop oxidative damage: their mitochondria actually make fewer ROS! These species have a special protein called alternative oxidase, or AOX. It works by shortening the pathway that mitochondria use to turn food into energy. A shorter pathway means fewer ROS are made. Scientists have been able to take the AOX gene and move it into other species.

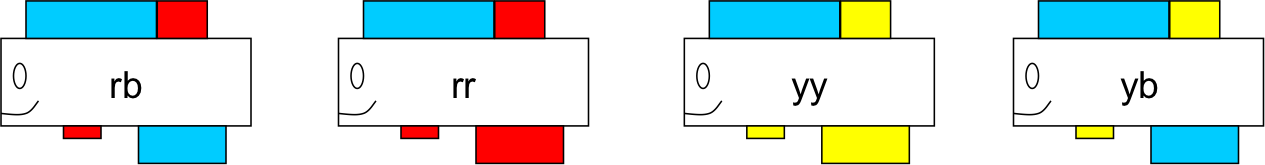

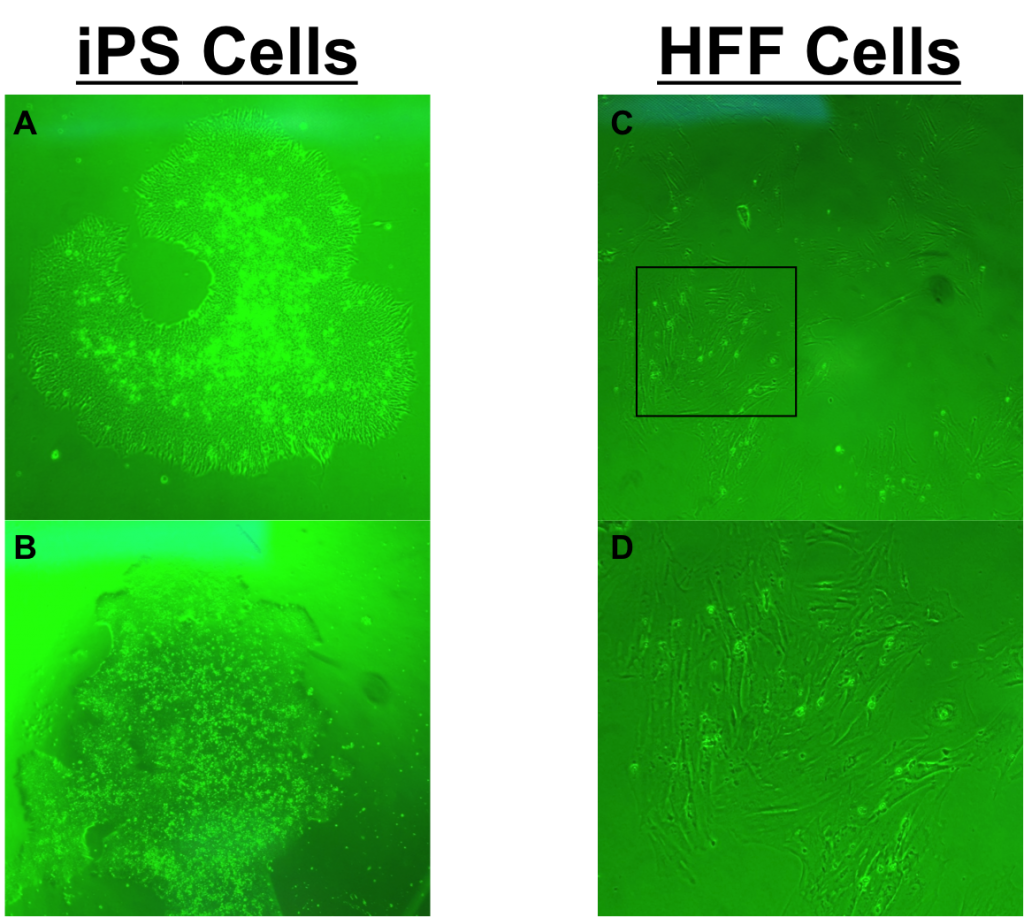

Biz, a scientist studying oxidative damage, wanted to study the effects of the DJ-1 mutation and the AOX gene. To do their research, Biz uses fruit flies. Fruit flies are useful because they are easy to work with and scientists can control the types of mutations and genes they have in the lab. Some of these mutations are the same as those found in humans, so scientists can use them to study human disease. In one study, scientists were able to take the AOX gene and put it into the fruit fly. Fruit flies can also have the DJ-1 mutation that stops antioxidants from being made. Biz used these genetic tools to work with flies that have less oxidative damage (AOX mutants), more oxidative damage (DJ-1 mutants), or normal levels (controls).

Biz was interested in how AOX and DJ-1 affect reproductive cells – sperm and eggs. Oxidative damage is even more dangerous for reproductive cells than for other cells. Whereas most cells can just self-destruct or stop replicating when they build up too much damage, sperm and eggs have to stay healthy up until the moment of fertilization. This wait can last a long time. In many species, females store the male’s sperm inside their own bodies for days, months, or even years after mating! In addition to making their own ROS and antioxidants, sperm and egg cells stored inside the female can be damaged or protected by ROS and antioxidants made by the female’s reproductive tract. Either way, damage to reproductive cells is very important because it can be passed on to future generations or can cause the offspring to die.

Biz wanted to test whether the level of oxidative damage in eggs and stored sperm would influence how many offspring a female had. If cells with oxidative damage do not produce healthy offspring, then fruit flies with less damage should have more offspring. Biz also expected that fruit flies with more damage should have fewer offspring. To test these ideas, Biz mated normal male fruit flies to three groups of females: females with the AOX gene, females with the DJ-1 mutation, and normal (“control”) females. Aside from having the AOX or DJ-1 gene, the females in all treatments were genetically the same. The males used in the experiment were also genetically identical. After the males and females mated, Biz counted the number of surviving offspring from each group.

Featured scientist: Biz Turnell from Cornell University and Technische Universität Dresden

About Carrie: I have been interested in animal behavior and behavioral ecology since my second year in college at the University of Tennessee. I am primarily interested in how variation in ecology and environment affect communication and signaling in birds. I have also studied various types of memory and am interested in how animals learn and use information depending on how their environment varies over space and time. I am currently working on my PhD in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology at the University of Nevada Reno and once I finish I hope to become a professor at a university so that I can continue to conduct research and teach students about animal behavior. In my spare time I love hiking with my friends and dogs, and watching comedies!

About Carrie: I have been interested in animal behavior and behavioral ecology since my second year in college at the University of Tennessee. I am primarily interested in how variation in ecology and environment affect communication and signaling in birds. I have also studied various types of memory and am interested in how animals learn and use information depending on how their environment varies over space and time. I am currently working on my PhD in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology at the University of Nevada Reno and once I finish I hope to become a professor at a university so that I can continue to conduct research and teach students about animal behavior. In my spare time I love hiking with my friends and dogs, and watching comedies!