The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 2

- PowerPoint of images and visual data

- Grading Rubric

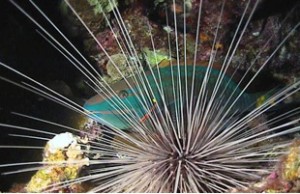

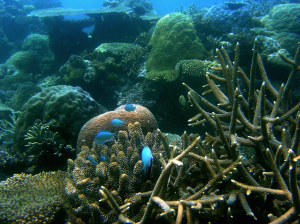

When you imagine a coral, you likely picture it living on a coral reef, bathed in sunlight, surrounded by crystal clear waters teeming with colorful fishes. But corals can actually live in a range of habitats, even habitats that are sometimes murky and much darker!

As marine biologists, Karina and John often snorkel around the mangroves in Belize, where they do their research. Mangroves are trees that have roots able to grow in saltwater. By capturing mud and sediment, these underwater roots build habitat for marine life. While Karina and John were documenting the different marine life that can grow on underwater roots, they noticed something shocking. The same corals that live on coral reefs were growing in the mangrove forests too! This surprised Karina and John because coral reefs and mangrove forests are very different habitats. Coral reefs have clear water and bright light, while mangrove forests are darker with murky water that has a lot of nutrients. How can corals live in such different places?

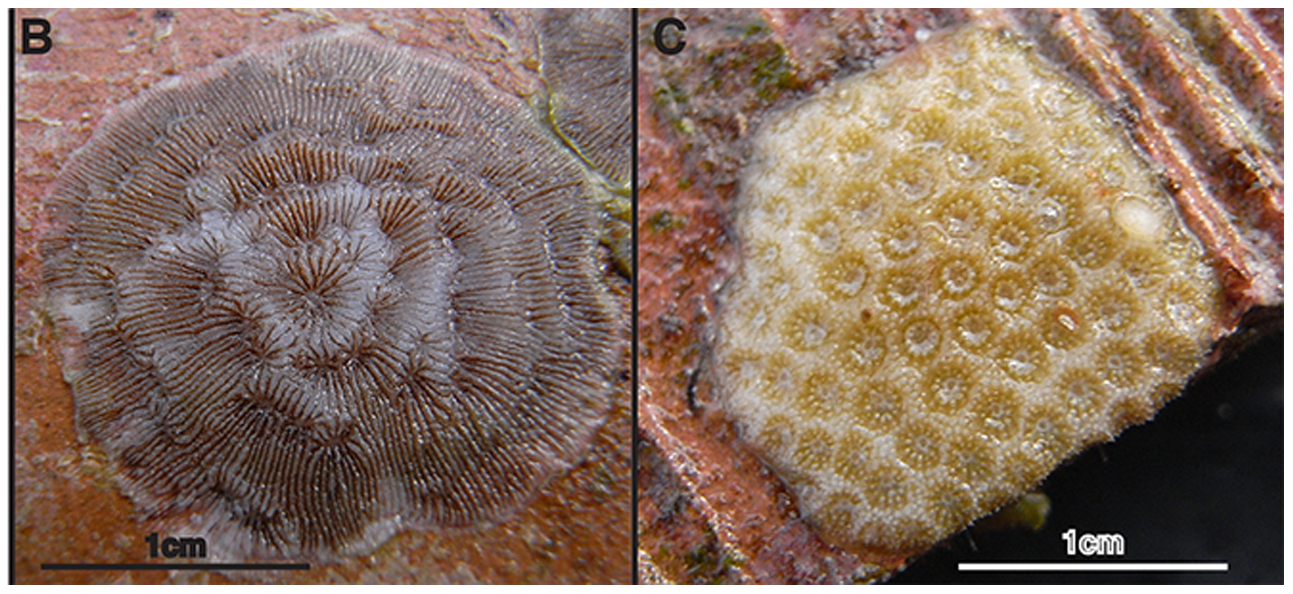

Karina and John started to wonder if the corals that live in the mangroves look different than the corals on the reefs. Sometimes animals can look different based on where they live. These differences may be adaptations that help them live in different environments. Karina and John measured differences between two different coral species that were found in both habitat types. The two species they used are the mounding mustard hill coral and the branching thin finger coral.

Featured scientists: Karina Scavo Lord and John Finnerty from Boston University

About Tina: I first became interested in science catching frogs and snakes in my backyard in Ithaca, NY. This inspired me to major in Biology at Cornell University, located in my hometown. As an undergraduate, I studied male competition and sperm allocation in the local spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. After graduating, I joined the Peace Corps and spent 2 years in Morocco teaching environmental education and 6 months in Liberia teaching high school chemistry. As a PhD student in the Buston Lab, I study how parents negotiate over parental care in my study system the clownfish, Amphiprion percula, otherwise known as Nemo.

About Tina: I first became interested in science catching frogs and snakes in my backyard in Ithaca, NY. This inspired me to major in Biology at Cornell University, located in my hometown. As an undergraduate, I studied male competition and sperm allocation in the local spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. After graduating, I joined the Peace Corps and spent 2 years in Morocco teaching environmental education and 6 months in Liberia teaching high school chemistry. As a PhD student in the Buston Lab, I study how parents negotiate over parental care in my study system the clownfish, Amphiprion percula, otherwise known as Nemo.