In Part I, you examined patterns of total bird abundance at Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest. These data showed bird numbers at Hubbard Brook have declined since 1969. Is this true for every species of bird? You will now examine data for four species of birds to see if each of these species follows the same trend.

The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

- Grading Rubric

- PowerPoint of images

- Digital Data Nugget on DataClassroom

It is very hard to study migratory birds because they are at Hubbard Brook only during their breeding season (summer in the Northern Hemisphere). They spend the rest of their time in the southeastern United States, the Caribbean or South America or migrating between their two homes. Therefore, it can be difficult to tease out the many variables affecting bird populations over their entire range. To start, scientists decided to focus on what they could study—the habitat types at Hubbard Brook and how they might affect bird populations.

Hubbard Brook Forest was heavily logged and disturbed in the early 1900s. Trees were cut down to make wood products, like paper and housing materials. Logging ended in 1915, and various plants began to grow back. The area went through what is called secondary succession, which refers to the naturally occurring changes in forest structure that happen as a forest recovers after it was cut down or otherwise disturbed. Today, the forest has grown back. Scientists know that as the forest grew older, its structure changed: Trees grew taller, the types of trees changed, and there was less shrubby understory. The forest now contains a mixture of deciduous trees that lose their leaves in the winter (about 80–90%; mostly beech, maples, and birches) and evergreen trees, mostly conifers, that stay green all year (about 10–20%; mostly hemlock, spruce, and fir).

Richard and his fellow scientists already knew a lot about the birds that live in the forest. For example, some bird species prefer habitats found in younger forests, while others prefer habitats found in older forests. They decided to look carefully into the habitat preferences of four important species of birds—Least Flycatcher, Red-eyed Vireo, Black-throated Green Warbler, and American Redstart—and compare them to habitats available at each stage of succession. They wondered if habitat preference of a bird species is associated with any change in the bird populations at Hubbard Brook since the beginning of succession.

- Least Flycatcher: The Least Flycatcher prefers to live in semi-open, mid-successional forests. The term mid-successional refers to forests that are still growing back after a disturbance. These forests usually consist of trees that are all about the same age and have a thick canopy at the top with few gaps, a relatively open area under the canopy, and a denser shrub layer close to the ground.

- Black-throated Green Warbler: The Black-throated Green Warbler occupies a wide variety of habitats. It seems to prefer areas where deciduous and coniferous forests meet and can be found in both forest types. It avoids disturbed areas and forests that are just beginning succession. This species prefers both mid-successional and mature forests.

- Red-eyed Vireo: The Red-eyed Vireo breeds in deciduous forests as well as forests that are mixed with deciduous and coniferous trees. They are abundant deep in the center of a forest. They avoid areas where trees have been cut or blown down and do not live near the edge. After an area is logged, it often takes a very long time for this species to return.

- American Redstart: The American Redstart generally prefers moist, deciduous, forests with many shrubs. Like the Least Flycatcher, this species prefers mid-successional forests.

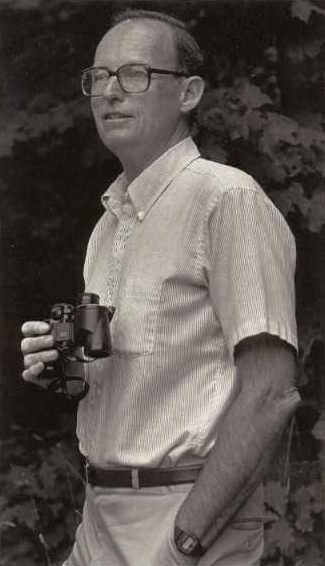

Featured scientist: Richard Holmes from the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest. Data Nugget written by: Sarah Turtle and Jackie Wilson.

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 10.6

Additional teacher resource related to this Data Nugget:

- There is an engaging video that can be used before the students begin the activity. It introduces some of the researchers behind this body of work, including Richard Holmes, and highlights the importance of the long-term nature of this dataset.

- For the full dataset associated with this Data Nugget, check out the Hubbard Brook Data Catalog page. Search for “Bird abundances” in the search bar to find the dataset.

- For more information on this research, check out the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest’s page on their songbird research

- For more lessons created from data collected on birds at Hubbard Brook, check out the page “Migratory Birds Math and Science Lessons from Hubbard Brook.”

There are multiple publications related to the data included in this activity:

- Holmes, R. T. 2011. Birds in northern hardwoods ecosystems: Long-term research on population and community processes in the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest. Forest Ecology and Management doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.06.021.

- Holmes, R.T., 2007. Understanding population change in migratory songbirds: long-term and experimental studies of Neotropical migrants in breeding and wintering areas. Ibis 149 (Suppl. 2), 2-13.

- Townsend, A. K., et al. (2016). The interacting effects of food, spring temperature, and global climate cycles on population dynamics of a migratory songbird. Global Change Biology 2: 544-555.

About Skye: As a child Skye was always asking why; questioning the behavior, characteristics, and interactions of plants and animals around her. She spent her childhood reconstructing deer skeletons to understand how bones and joints functioned and creating endless mini-ecosystems in plastic bottles to watch how they changed over time. This love of discovery, observation, questioning, and experimentation led her to many technician jobs, independent research projects, and graduate research study at Purdue University. At Purdue she studies the factors influencing oak regeneration after ecologically based timber harvest and prescribed fire. While Skye’s primary focus is ecological research, she loves getting to leave the lab and bring science into classrooms to inspire the next generation of young scientists and encourage all students to be always asking why!

About Skye: As a child Skye was always asking why; questioning the behavior, characteristics, and interactions of plants and animals around her. She spent her childhood reconstructing deer skeletons to understand how bones and joints functioned and creating endless mini-ecosystems in plastic bottles to watch how they changed over time. This love of discovery, observation, questioning, and experimentation led her to many technician jobs, independent research projects, and graduate research study at Purdue University. At Purdue she studies the factors influencing oak regeneration after ecologically based timber harvest and prescribed fire. While Skye’s primary focus is ecological research, she loves getting to leave the lab and bring science into classrooms to inspire the next generation of young scientists and encourage all students to be always asking why!