The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 2

- Grading Rubric

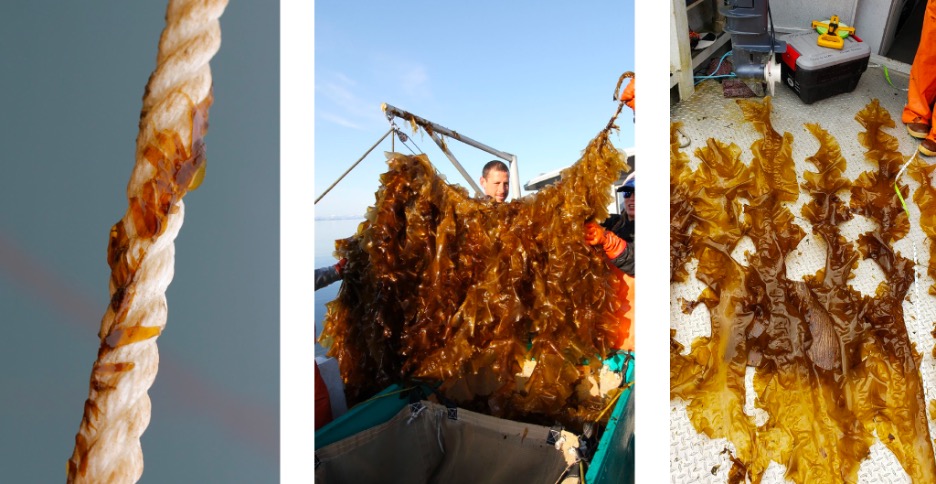

When thinking about farming, many people imagine fields of corn or soybeans, or even their own vegetable garden. All of these crops are grown on land, but what about growing food in the ocean? Alaska Natives who live along the coast have been harvesting kelp, a group of seaweeds, from the wild for thousands of years. Kelp is very nutritious and is full of vitamins and minerals. It is used in a variety of dishes, from soups to salads. Kelp also provides structure for herring to lay their eggs, another traditional food source that coastal Alaska Native communities harvest. Kelp has other purposes too, including soil fertilizer and food additive applications.

Recently, there has been a surge of interest in farming kelp at a larger scale along the Alaskan coast. Farming kelp involves cultivating kelp at a site to grow larger for harvest. Caitlin is a biologist who works for the Native Village of Eyak within the Prince William Sound of Alaska. The Tribe wants to start a kelp farm to provide a nutritious food source for its community members. Caitlin was tasked with designing the farm setup and testing how much kelp can be grown. Her first step was to find a site. She had to consider environmental factors that help the kelp grow. Kelp need particular nutrients and cool water temperatures. She also had to make sure the site was easy to get to and that it was protected from intense weather like high winds and large waves.

To get started, Caitlin talked to the members of the Eyak community to learn where they have historically found kelp, called Traditional Knowledge. She listened to their suggestions, which were based on current and long-term connections with the local environment. This helped her identify a site that is a short boat ride. Caitlin also had discussions with other kelp farmers in Alaska and read scientific research articles to learn more about how to set up a kelp farm and which species would be a good fit. She decided to grow sugar kelp because it has a sweeter taste and grows well in other places with similar conditions.

She designed the farm to grow the kelp vertically in the water. To do this, she would place lines vertically in the water for kelp to attach and grow at different depths. This design maximizes the amount of kelp grown below the surface, which is good to minimize interference with boats and animals. While vertical lines have benefits, there could be drawbacks too. Kelp needs sunlight for photosynthesis, which it uses to grow. But the deeper you go in the water, the less sunlight there is. The kelp at the surface will get plenty of light, but the kelp attached to the line in deeper water might not get enough. The kelp at the bottom could also get blocked or shaded by the kelp above it.

Caitlin wanted to know if there is a time of year when kelp had the fastest growth rates. This information would help her know when to harvest kelp from the site. She also wanted to know whether depth affected the kelp growth. If it turned out that kelp didn’t grow on her vertical lines in deeper water, she may have to try another design. She predicted that kelp grown in the first 1-2 meters from the surface would grow more over a season because it would receive the most sunlight.

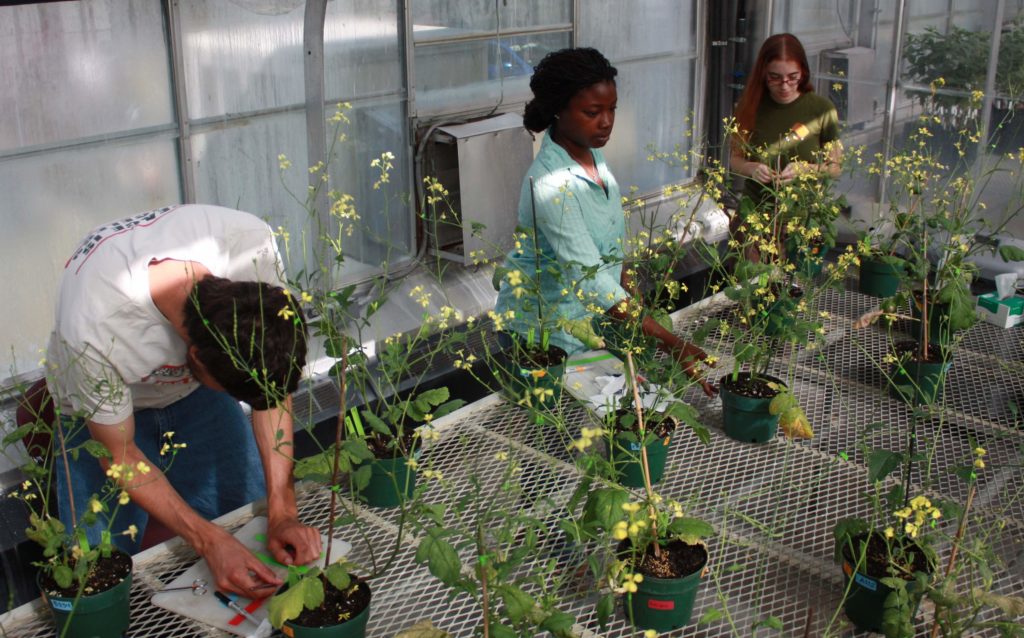

To assess her kelp farm plan, Caitlin worked with partners to seed lines with fertilized sugar kelp spores. Each of these spores can grow into a large kelp blade that can be up to 5 meters long. The seeded lines were then installed vertically at the farm site in the fall of 2022. Caitlin and her colleagues set up 532 vertical lines that were each 10 meters long. In total, over 2 miles of seeded line were installed on the farm! The lines were attached to a horizontal line to secure them in place and were spaced out so they had room to grow.

Each month, Caitlin and her colleagues monitored the kelp growth by measuring the length of kelp blades, or leaf-like structures, on 5-8 of the seeded lines. On each line, they measured kelp blades at different depths so they could see how the kelp was growing at different depths.

Featured scientist: Caitlin McKinstry (she/her) from the Native Village of Eyak. Written with Rosel Burt and Melissa Kjelvik from Prince William Sound College.

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 7.4

Additional teacher resource related to this Data Nugget:

- Video for students to visualize what mariculture looks like and to hear perspectives from many groups about the growing industry.

- More information, history, and insight about the Native Village of Eyak’s mariculture program.

- Ocean rainforest has more videos about kelp farming and the latest news in this field

- The Ologies podcast has an episode on seaweed, Macrophycology, that explains many of these similarities and differences.

- Video on the potential for kelp farms to create additional habitat for animals.

- Read an overview of Alaska mariculture at the Prince William Sound Science Center’s page.

This Data Nugget created with funding from the NSF Alaska EPSCoR Interface of Change.