The color polymorphism in bluefin killifish – males display anal fins in blue, red, or yellow.

Why so blue? The determinants of color pattern in killifish

For more information on the NABT 2016 conference, check out their website, here.

Why be blue in a swamp? The evolution of color patterns and color vision in killifish

Animal communication happens when one organism emits a signal, which then travels through the environment and is detected by the sensory system of another. The environment in which signaling occurs can dramatically alter signal transmission and result in selection where different signals are favored in different environments. The bluefin killifish provide a compelling example. Some populations are found in crystal clear springs (where UV and blue light are highly abundant) and others are found in tannin-stained swamps (where UV/blue light is depauperate). Paradoxically, males with blue color patterns are abundant in swamps and are rare in springs. The resolution to this paradox requires a consideration of how genetics and the environment influence trait expression, as well as the direction of natural and sexual selection in different habitat types, and the manner in which animals with different visual systems perceive the same color pattern.

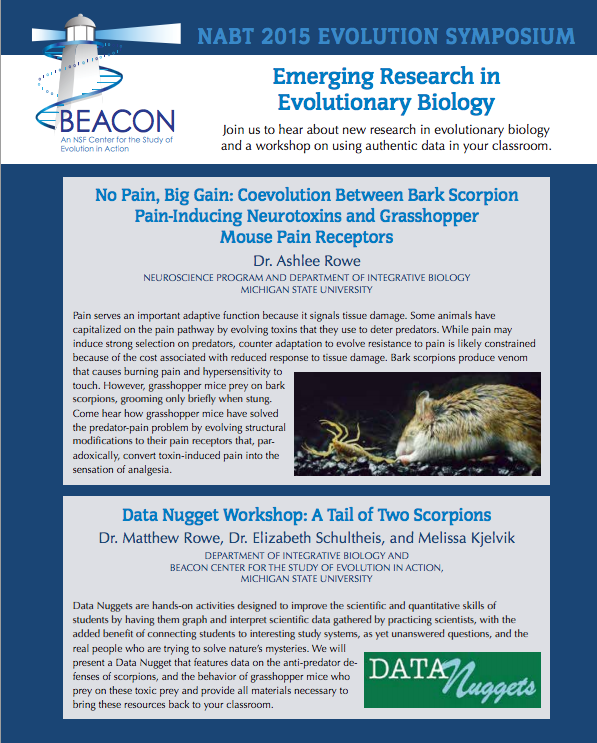

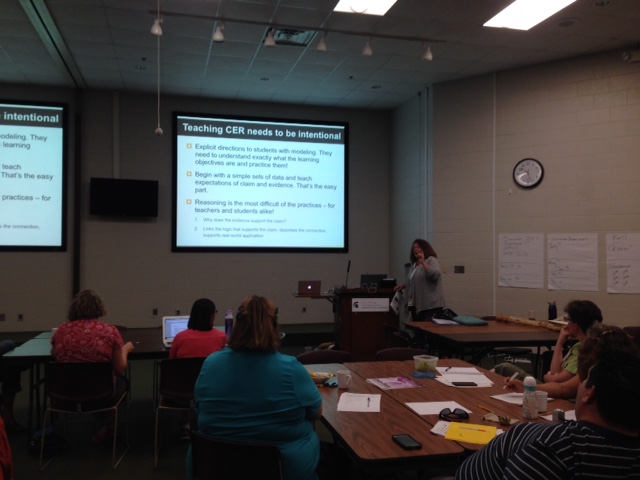

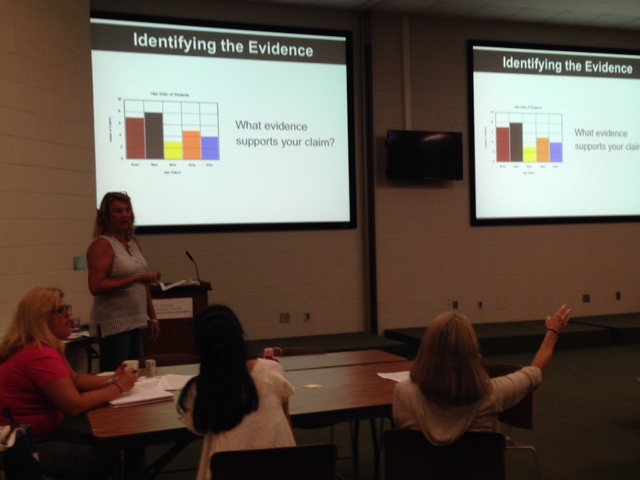

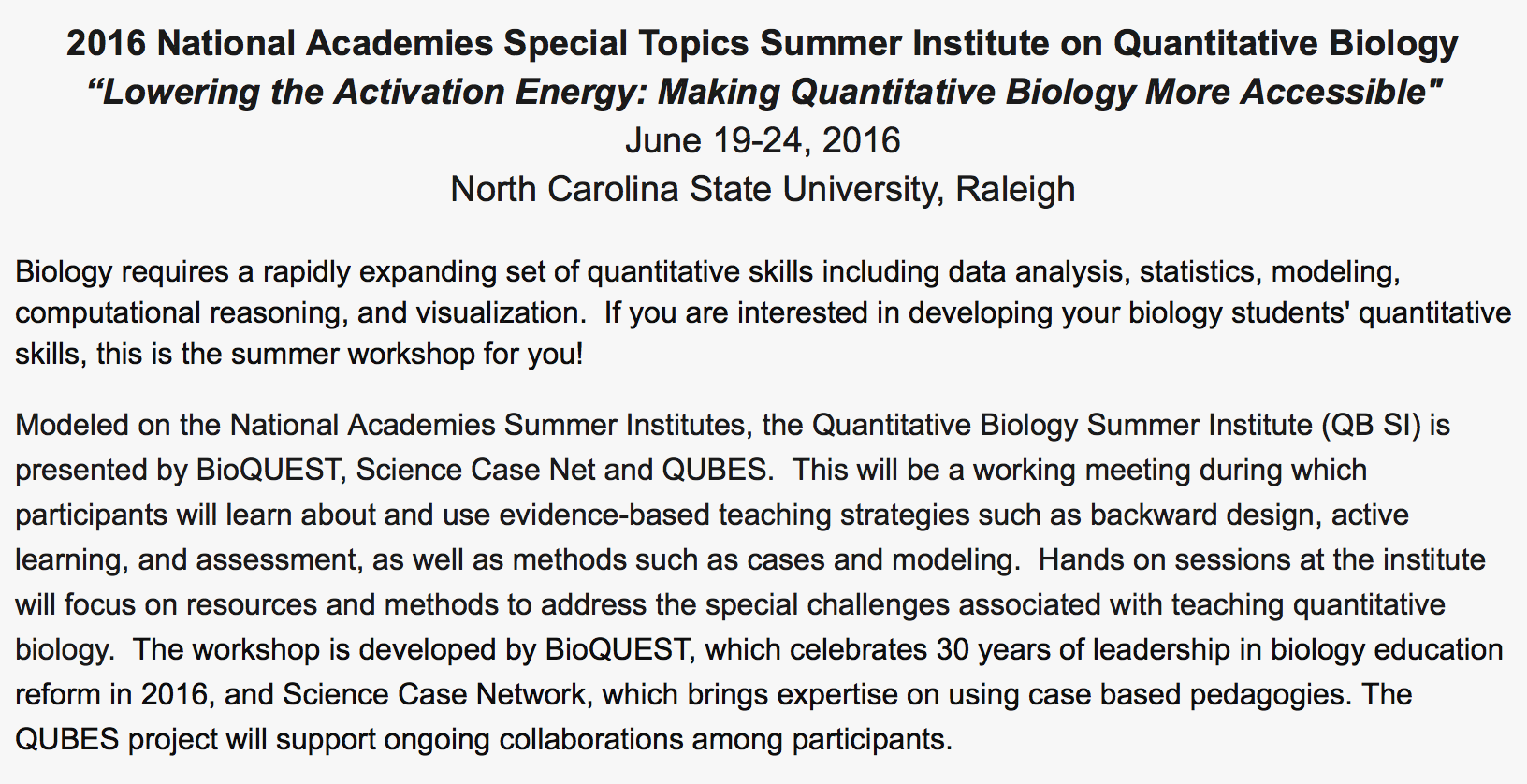

Data Nugget Workshop: Why so blue? The determinants of color pattern in killifish

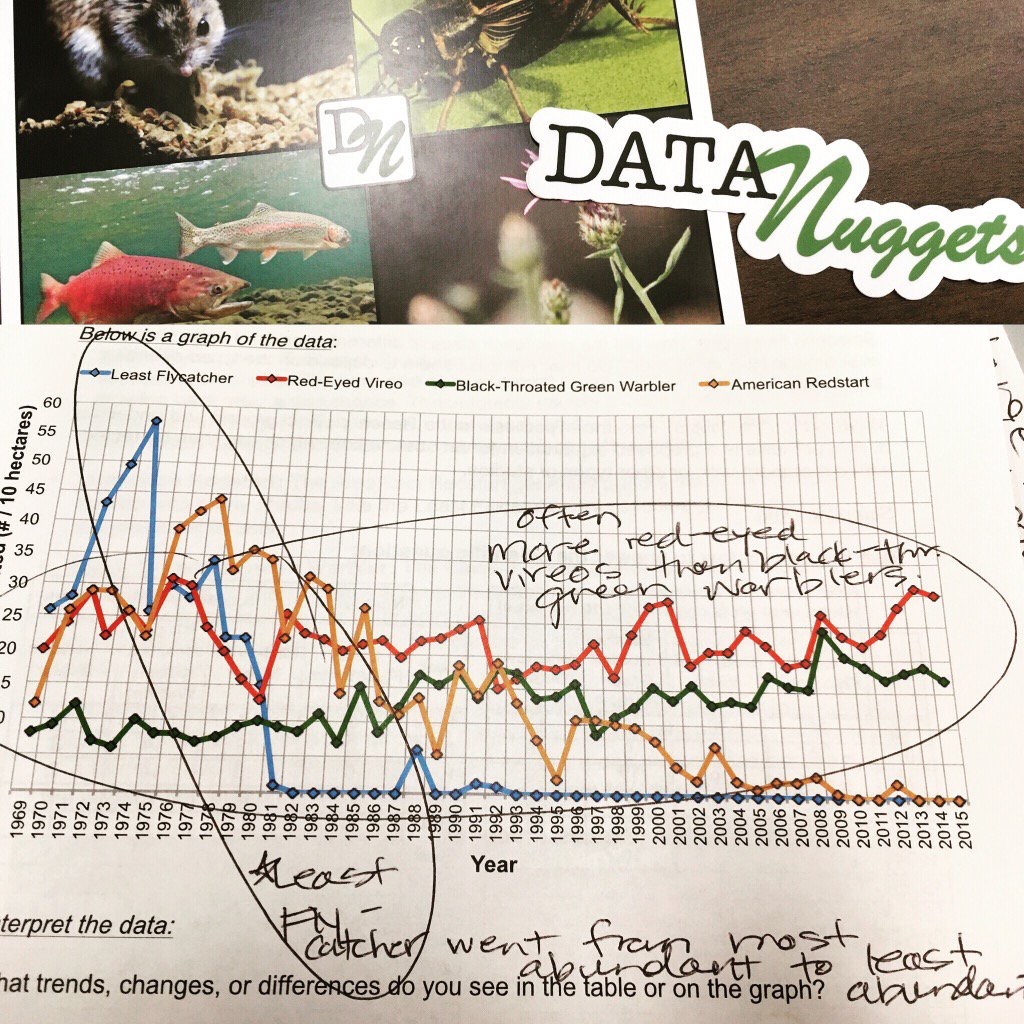

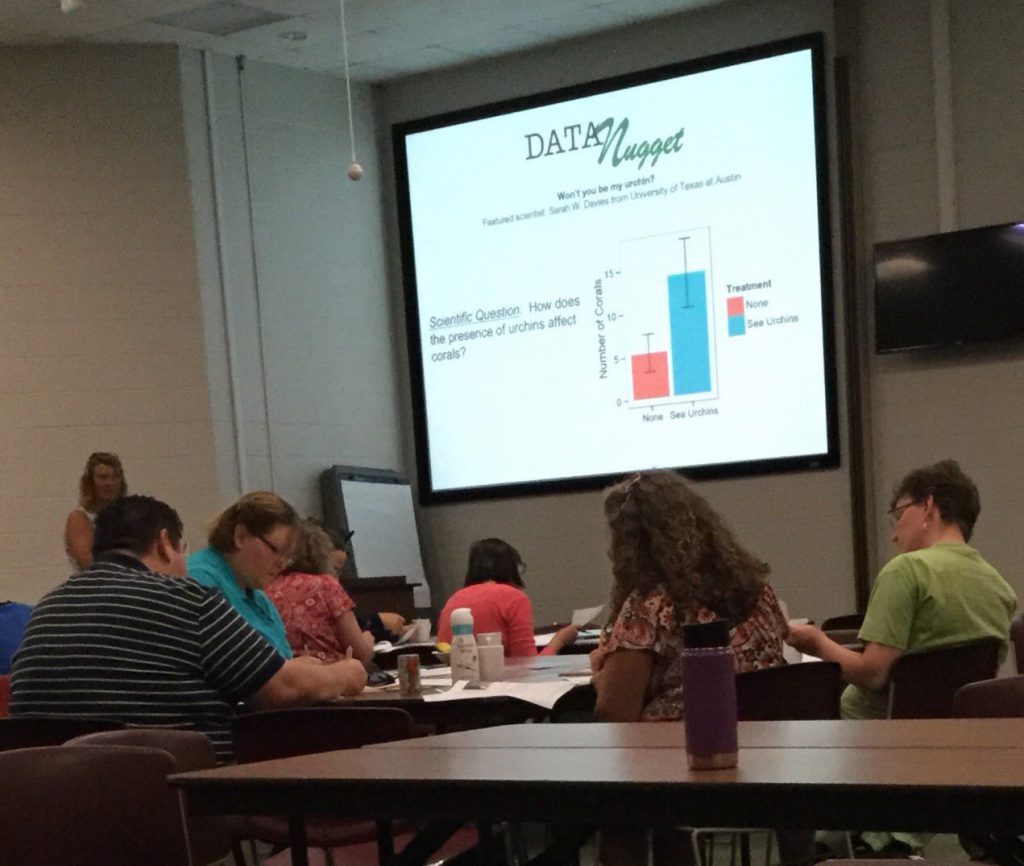

Data Nuggets are hands-on activities designed to improve the scientific and quantitative skills of students by having them graph and interpret scientific data gathered by practicing scientists. This workshop will provide an overview of Data Nuggets and present a Data Nugget featuring data on the genetic and environmental basis of color pattern expression in killifish. This Data Nugget will allow students to determine whether color pattern expression is due to ‘nature’ (e.g., genetics), ‘nurture’ (e.g. environment), or the interaction of the two.

![]() The materials from the Data Nugget workshop are as follows:

The materials from the Data Nugget workshop are as follows:

- Talk PowerPoint slides

- Why so blue? Data Nugget – Part I

- Why so blue? Data Nugget – Part II

- Data Nugget Guide to Graphing

- CER Explanation Tool

- Grading Rubric

Workshop organized and presented by: Becky Fuller, Elizabeth Schultheis, Melissa Kjelvik, Alexa Warwick, and Louise Mead

BEACON CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF EVOLUTION IN ACTION, MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY & UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS

All the participants at the

All the participants at the