Image of a humpback whale tail from the Palmer Station LTER. Photo credit Beth Simmons.

The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 4

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 4

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 4

- PowerPoint of images from Palmer LTER

- Grading Rubric

- Digital Data Nugget on DataClassroom

People have hunted whales for over 5,000 years for their meat, oil, and blubber. In the 19th and 20th centuries, pressures on whales got even more intense as technology improved and the demand for whale products increased. This commercial whaling used to be very common in several countries, including the United States. Humpback whales were easy to hunt because they swim slowly, spend time in bays near the shore, and float when killed. Before commercial whaling, humpback whales were one of the most visible animals in the ocean, but by the end of the 20th century whaling had killed more than 200,000 individuals.

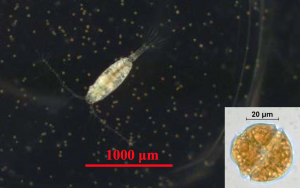

Today, as populations are struggling to recover from whaling, humpback whales are faced with additional challenges due to climate change. Their main food source is krill, which are small crustaceans that live under sea ice. As sea ice disappears, the number of krill is getting lower and lower. Humpback whale population recovery may be limited because their main food source is threatened by ongoing ocean warming.

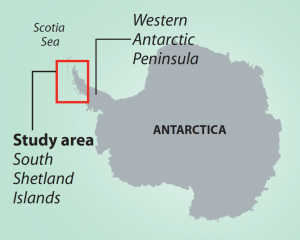

One geographic area that was over-exploited during times of high whaling was the South Shetland Islands along the Western Antarctic Peninsula (WAP). The WAP is in the southern hemisphere in Antarctica. Humpback whales migrate every year from the equator towards the south pole. In summer they travel 25,000 km (16,000 miles) south to WAP’s nutrient-rich polar waters to feed, before traveling back to the equator in the winter to breed or give birth. Today the WAP is experiencing one of the fastest rates of regional climate change with an increase in average temperatures of 6° C (10.8° F) since 1950. Loss of sea ice has been documented in recent years, along with reduced numbers of krill along the WAP.

One geographic area that was over-exploited during times of high whaling was the South Shetland Islands along the Western Antarctic Peninsula (WAP). The WAP is in the southern hemisphere in Antarctica. Humpback whales migrate every year from the equator towards the south pole. In summer they travel 25,000 km (16,000 miles) south to WAP’s nutrient-rich polar waters to feed, before traveling back to the equator in the winter to breed or give birth. Today the WAP is experiencing one of the fastest rates of regional climate change with an increase in average temperatures of 6° C (10.8° F) since 1950. Loss of sea ice has been documented in recent years, along with reduced numbers of krill along the WAP.

Logan is a scientist who is studying how humpback whales are recovering after commercial whaling. Logan’s work helps keep track of the number of whales that visit the WAP in the summer. He also determines the sex ratio, or ratio of males to females, which is important for reproduction. The more females in a population compared to males, the greater the potential for having more baby whales born into the next generation. Logan predicts there may be a general trend of more females than males along the WAP as the season progresses from summer to fall. Logan thinks that female humpback whales stay longer in the WAP because they need to feed more than males in order to have extra nutrients and energy before they birth their babies later in the year. This extra energy will be needed for their milk supply to feed their babies.

The Palmer LTER station when Logan and others scientists live while they conduct research on whales.

Humpback whales only surface for air for a short period of time, making it difficult to determine their sex. In order to identify surfacing whales as female or male, scientists need to collect a biopsy, or a sample of living tissue, in order to examine the whale’s DNA. Logan worked with a team of scientists at Oregon State University and Duke University to engineer a modified crossbow that could be used to collect samples. Logan uses this crossbow to collect a biopsy sample each time they spot a whale. To collect a sample, Logan aims the crossbow at the whale’s back, taking care to avoid the dorsal fin, head, and fluke (tail). He mounts each arrow with a 40mm surgical stainless steel tip and a flotation device so the samples will bounce off the whale and float for collection. The samples are then frozen so they can be stored and brought back to the lab for analysis. Logan also takes pictures of each whale’s fluke because each has a pattern unique to that individual, just like the human fingerprint. Additionally, at the time of biopsy, Logan records the pod size (number of whales in the area) and GPS location.

Logan’s data are added to the long-term datasets collected at the WAP. To address his question he used data from 2010-2016 along the WAP and other feeding grounds. Logan’s data ranges from January to April because those are the months he is able to spend at the research station in the WAP before it gets too cold. Logan has added to the scientific knowledge we have about whales by building off of and using data collected by other scientists.

Featured scientist: Logan J. Pallin from Oregon State University. Written by: Alexis Custer

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 10.7

Additional teacher resources related to this Data Nugget:

Additional teacher resources related to this Data Nugget:

- To see more images of humpback whales, and the Palmer Research Station in the WAP where Logan works, check out this PowerPoint. This can be shared with students in class after they read the Research Background and before they move on to the data.

- More data from this region can be found on the DataZoo, Palmer LTER’s online data portal. To access data on this portal, follow instructions found on this “cheat sheet”. For files that have been compiled for educators, check out this Google Drive folder.

For his research, Logan has traveled to United States Antarctic Programs’ Palmer Research Station on the WAP during the austral summer and fall and will be departing again for the WAP in January 2018. He is part of a team of scientists interested in Palmer Long Term Ecological Research, which is funded through the National Science Foundation, documenting changes on in the Antarctic ecosystem.

For his research, Logan has traveled to United States Antarctic Programs’ Palmer Research Station on the WAP during the austral summer and fall and will be departing again for the WAP in January 2018. He is part of a team of scientists interested in Palmer Long Term Ecological Research, which is funded through the National Science Foundation, documenting changes on in the Antarctic ecosystem.- For more information on whale research at Palmer Station LTER and the WAP, check out this website.

- For additional classroom activities dealing with Palmer Station LTER data, check out this website.

- The International Whaling Commission (IWC) was created in

1946 in Washington D.C. in hopes to provide conservation to whale stocks around the world. In 1982, the IWC placed a moratorium on commercial whaling. Fore more information on the IWC and humpback whales, check out their website.

About Logan: Logan is interested in determining how humpback whales are recovering after commercial whaling. Logan first got interested in working with marine mammals when he was an undergraduate student at Duke University and had the opportunity to work as a field technician on a project with some scientists at Duke. He quickly realized this was what he wanted to do and that studying humpbac whales was particularly interesting as they appear to have all rebounded quite heavily in the Southern Hemisphere. Assessing why this recovery was happening so fast and why now, was something Logan really wanted to look at. After graduating from college, he continued to work with marine mammologists as a graduate student to receive his Masters in Science from Oregon State University. In the fall of 2017, he started his work on a PhD from University of California, Santa Cruz continuing asking questions and learning more about whales around Antarctica.