Forests in the midwestern U.S. provide many important ecological services. They store carbon dioxide, which helps fight climate change. They also host a variety of plant and animal life. Forests provide spaces for recreation and support local economies through tourism.

Unfortunately, forests face threats. Climate change is causing more severe weather events, such as flooding and droughts. The spread of some parasites and diseases is also increasing as temperatures change. Forest managers are motivated to protect forest health. They can help combat these threats with their knowledge of different management practices.

Ellen and John have studied forest health in Wisconsin for decades. Ellen first became interested in nature while camping and hiking in Minnesota with her family when she was young. John became passionate about nature as a child while walking through the oak-hickory forests on his family farm. They teamed up with foresters from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to examine the impact of prescribed fire as a management tool to increase forest health. A prescribed fire differs from a wildfire in that it is a planned fire that is set on purpose. When the conditions are right, forest managers will assign prescribed fires to specific areas to meet land management objectives. A lot of organization goes into prescribed fires to make sure the fire doesn’t spread or burn too hot.

Fire is part of the natural history of oak forests. They are adapted to recover quickly and they actually can benefit from fire. This is important for land managers who want to encourage the health of oak forests.

Oaks are considered a keystone species. This means they play a major role in maintaining ecosystem functions and the success of other species. There are two main reasons. First, they produce large amounts of acorns, which are food for many types of wildlife. Second, their canopies have more open spaces that allow light to reach the forest floor. Light is an important resource for plants, and smaller plants are limited by the shade of large trees. More light passing through the canopy allows more plants to grow below the oak trees. This increases the variety of species found in oak forests.

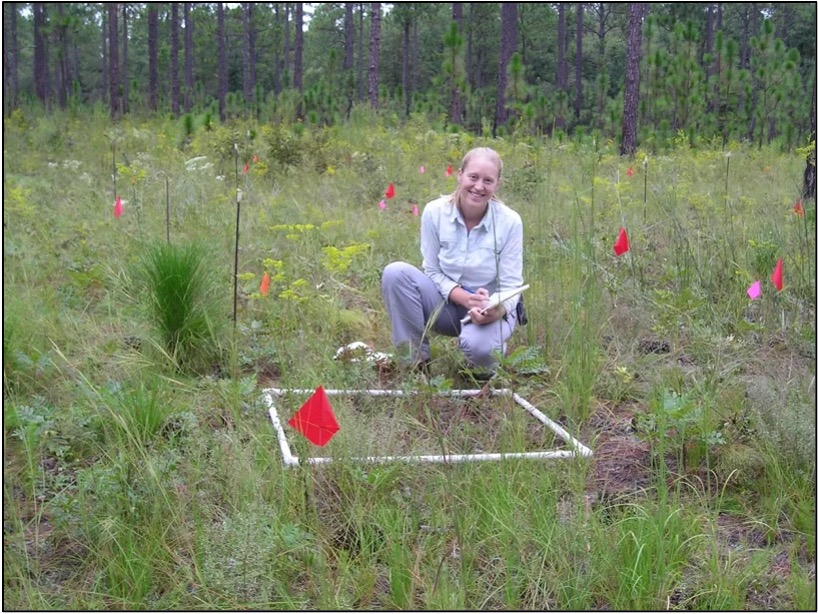

Ellen and John wanted to know if there were more plant species in oak forests that had prescribed fires. To answer their question, Ellen and John decided to study a part of the Madison School Forest in southwestern Wisconsin. This oak forest is special because research has been done on the impact of fire for over 75 years. In 1996, the forest was split into 15 units that have been under different management plans. One of the experimental treatments included prescribed fire at different frequencies. For example, the units in the prescribed fire treatment could have been burned every 1 to 4 years. Other units served as a control and were not burned. Comparing the control to plots that had been burned allows managers to see how often oak forests should be burned to increase forest health.

All of the management units were sampled in 1996 when the experiment first began and again in 2002 and 2007. In each sampling year, the number of plant species, or species richness, in the management units was counted. In 2023, Ellen, John, and their team resampled the plots to pick up this experiment where it was left off. This research will guide the best ways to support the health of oak forests and determine how important fire is to maintaining forest biodiversity. If fire is necessary to maintain oak forests, and oaks are a keystone species that support biodiversity, the research team expects to find higher biodiversity in plots where prescribed fire has been used.

Featured scientists: Ellen Damschen (she/her) and John Orrock (he/him) from

University of Wisconsin-Madison. Written by: Amy Workman (she/her)