A male anole lizard showing his bright dewlap.

The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

- PowerPoint of images and graphs

- Grading Rubric

Natural selection happens when differences in traits within a population give some individuals a better chance of surviving and reproducing than others. Traits that are beneficial are more likely to be passed on to future generations. However, sometimes a trait may be helpful in one context and harmful in another. For example, some animals communicate with other members of their species through visual displays. These signals can be used to defend territories and attract mates, which helps the animal reproduce. However, these same bright and colorful signals can draw the unwanted attention of predators.

Brown anoles are small lizards that are abundant in Florida and the Caribbean. They have an extendable red and yellow flap of skin on their throat, called a dewlap. To communicate with other brown anoles, they extend their dewlap and move their head and body. Males have particularly large dewlaps, which they often display in territorial defense against other males and during courtship with females. Females have much smaller dewlaps and use them less often.

Aaron with a baby anole lizard.

Aaron is a scientist interested in how natural selection might affect dewlap size in male and female brown anoles. He chose to work with anoles because they are ideal organisms for studies of natural selection; they are abundant, easy to catch, and have short life spans. Aaron wanted to know whether natural selection was acting in different ways for males and females to cause the differences in dewlap size. He thought that a male with a larger dewlap may be more effective at attracting females and passing on his genes to the next generation. However, males with larger, showy dewlaps may catch the eye of more predators and have higher chances of being eaten. Aaron was curious about this tradeoff and how it affected natural selection on dewlap size. For female brown anoles, Aaron thought that this tradeoff would be less important for survival because females have smaller dewlaps and use them less frequently as a signal. In other words, there may not be selection on dewlap size in females.

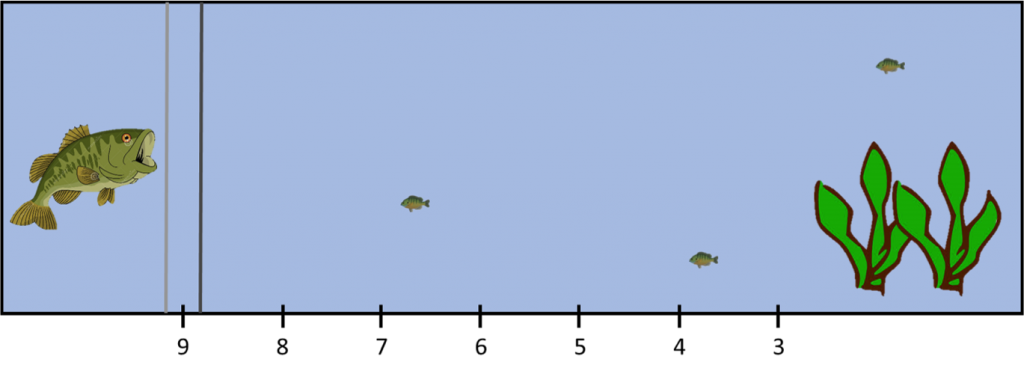

Using a population of brown anoles on a small island in Florida, Aaron set up a study to determine how dewlap size is related to survival and whether there is a difference between the sexes. He worked with his advisor, Robert, and other members of the lab. They designed a study to track every brown anole on the island and see who survived. In May 2015, they caught the adult lizards on the island and recorded their sex, body length, and dewlap size before releasing them with a unique identification number. Then, the lab returned to the island in October and collected all the adults once again to determine who survived and who didn’t. Aaron predicted that male anoles with larger than average dewlap size would be less likely to survive due to an increased risk of predation. He also predicted that dewlap size would not influence female survival.

Featured scientists: Aaron Reedy and Robert Cox from the University of Virginia. Co-written by undergraduate researcher Cara Giordano.

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 10.3

Additional teacher resource related to this Data Nugget:

- For additional images of Robert and Aaron’s research with anoles in Florida, we have created PowerPoint slides that can be shown in class.

- Aaron conducted this research as a graduate student in Robert Cox’s lab. To learn more about anole research, visit the lab’s website. To learn more about Aaron, visit his website.

- To engage students before the Data Nugget and introduce them to brown anoles, check out this video that shows how brown anoles use dewlap signaling to attract mates and send rival males signals during confrontations:

About Tina: I first became interested in science catching frogs and snakes in my backyard in Ithaca, NY. This inspired me to major in Biology at Cornell University, located in my hometown. As an undergraduate, I studied male competition and sperm allocation in the local spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. After graduating, I joined the Peace Corps and spent 2 years in Morocco teaching environmental education and 6 months in Liberia teaching high school chemistry. As a PhD student in the Buston Lab, I study how parents negotiate over parental care in my study system the clownfish, Amphiprion percula, otherwise known as Nemo.

About Tina: I first became interested in science catching frogs and snakes in my backyard in Ithaca, NY. This inspired me to major in Biology at Cornell University, located in my hometown. As an undergraduate, I studied male competition and sperm allocation in the local spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. After graduating, I joined the Peace Corps and spent 2 years in Morocco teaching environmental education and 6 months in Liberia teaching high school chemistry. As a PhD student in the Buston Lab, I study how parents negotiate over parental care in my study system the clownfish, Amphiprion percula, otherwise known as Nemo.