The activities are as follows:

- Teacher Guide

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 2

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 2

- PowerPoint of images

- Grading Rubric

Plants and animals have adaptations, or traits that help them survive and pass on more of their genes to the next generation. Flowers are a key adaptation for plants because they help the attract pollinators and reproduce.

Flowers come in many different shapes, sizes, colors, and forms. While flowers as a whole are an adaptation, traits within flowers are often adaptations themselves. For example, different flower colors attract different types of animals to the plant. Some flowers make nectar that gives animals a food reward for visiting. Other plants have small flowers with no petals so that pollen can be easily picked up and travel by wind.

Many of the animals that visit the plant serve as pollinators. Pollinators help plants reproduce by bringing reproductive parts together. Pollination happens when pollen from the stamen reaches the stigma. This is needed for seeds to form. By moving pollen, pollinators help plants make more seeds. More seeds lead to more plants in the next generation. Small differences in flower traits can change which plant is the most successful at reproducing and setting seed.

Jeff is a scientist studying a very particular flower shape seen in plants of the mustard family. Most plants in this family have flowers with 4 long stamens and 2 short stamens. No other plants have this shape, and no one knows why! The short stamens are a particular mystery.

Jeff wanted to see why mustards might have these short stamens. He thought that short stamens are an adaptation because they make it harder for pollinators to reach the pollen, so that more pollen would be left over for later pollinators. This might be beneficial because the first pollinator visiting the flower wouldn’t be able to take all the pollen, leaving none for the following visitors. If his hypothesis was correct, he predicted that short stamens would have less pollen removed with each pollinator visit compared the long stamens.

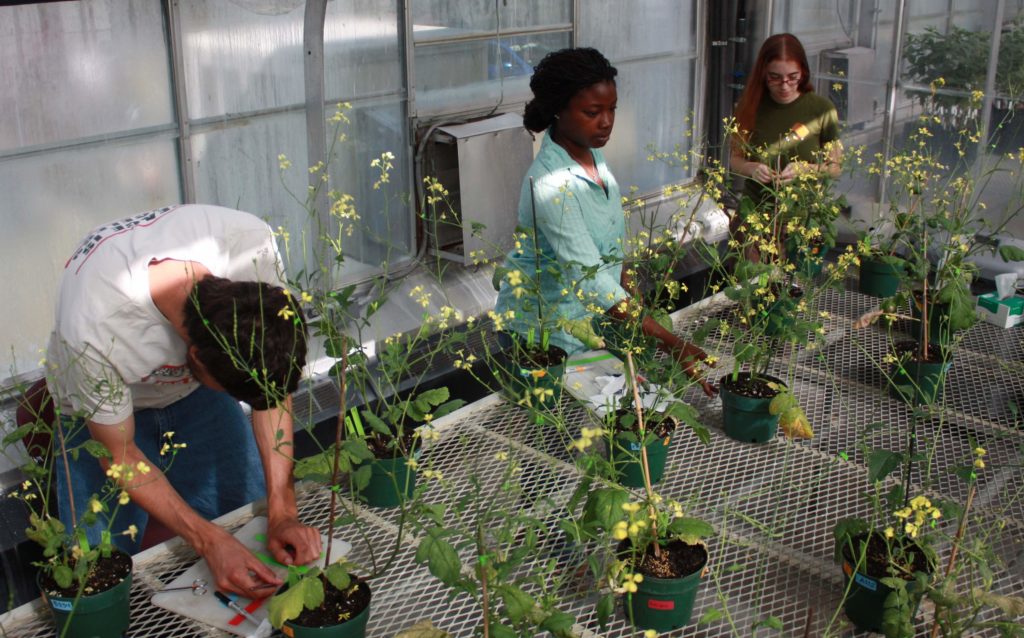

To collect his data, Jeff and other scientists in his lab needed to measure how much pollen was removed by pollinators on short and long stamens. To do this, they grew mustard plants in the greenhouse and let them flower. This made sure no pollinators could visit the plants before the experiment. Next, they exposed the plants to the three most common pollinators for mustards – bumblebees, small bees, and syrphid flies. To test honeybees, plants were put into flight cages with bees inside. To test small bees and syrphids, plants were put outside. Pollinators chose the flower to visit. After each visit, the lab counted the pollen on the visited flower. They then compared it to the amount of pollen on a flower that was not visited. They used these values to calculate the percent pollen removed. This was repeated for short and long stamens.

Featured scientists: Jeff Conner (he/him) from the W.K. Kellogg Biological Station. Written with Kirsten Salonga, Justice High School, Research Experience for Teachers.

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 7.6

Additional teacher resource related to this Data Nugget:

The data featured in this activity has been published. If you are interested in having students read primary scientific literature, they can complete this Data Nugget and then explore the full study here:

- Conner, J. K., R. Davis, and S. Rush. 1995. The effect of wild radish floral morphology on pollination efficiency by four taxa of pollinators. Oecologia 104: 234-245.