When given emergency instructions on a flight, you’re told to put on your own oxygen mask before assisting others. This is because if you run out of oxygen, you won’t be able to help others. Turning to nature, this same idea may be true when we look at relationships between two species.

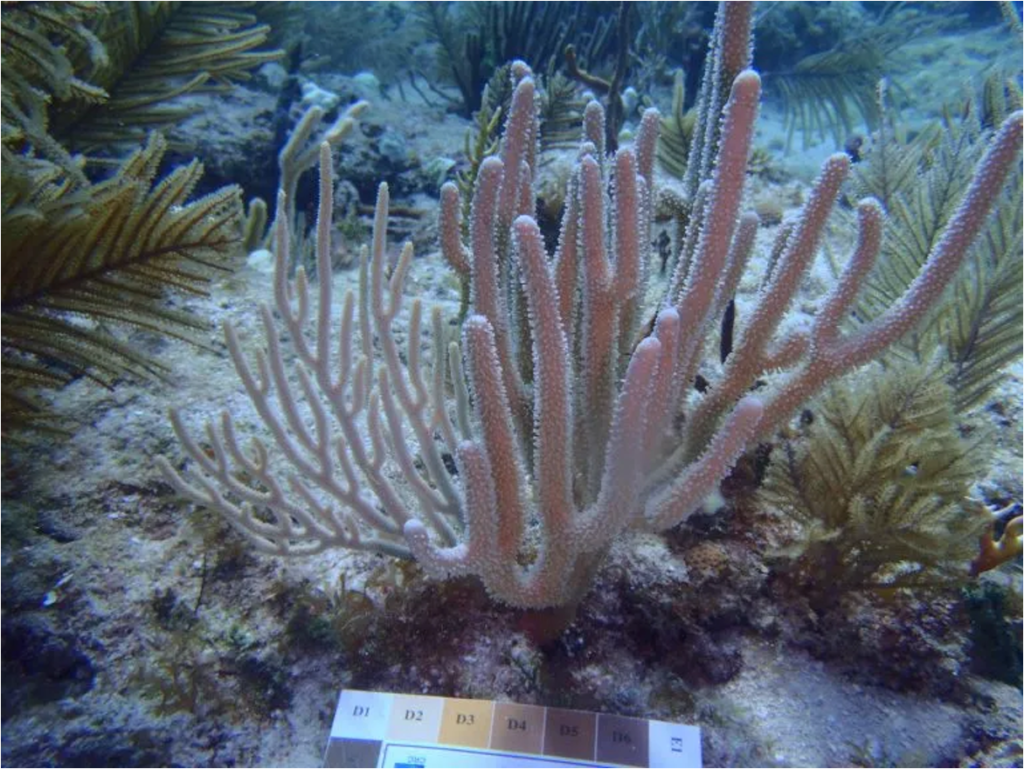

Coral and certain types of algae form a mutualism where both species benefit from the partnership. Coral provides a safe home for algae, and algae make food for coral through photosynthesis. However, climate change is causing warmer ocean temperatures that stress the relationship. If the water gets too hot for algae, they can’t make food for the coral anymore. To survive, the algae must help themselves before they can help the coral.

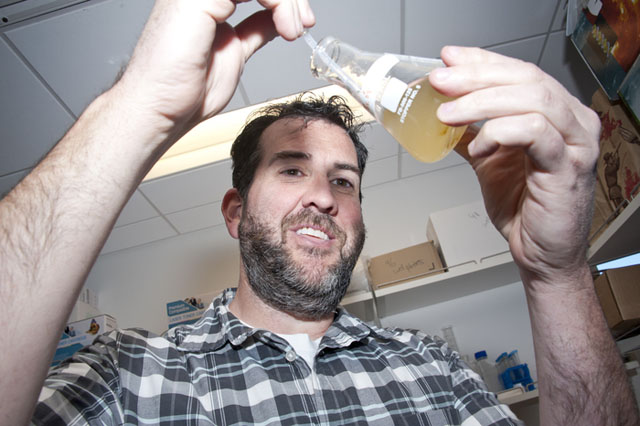

Casey is a biologist interested in studying the changing coral-algae mutualism. He wants to know whether different individuals of the same algae species do better than others in warming waters. Individuals of the same species can have different traits. For example, each human person belongs to the same species, but each of us has different traits. This is largely because of our genetic composition for these traits, or genotypes. Casey set out to test if different algae genotypes were capable of being better mutualists under warm temperatures. If he could identify these genotypes, then maybe that could help protect coral in the future.

Casey and his graduate student, Richard, set up experiments to test algae genotypes to see how well they performed at different temperatures. Casey and Richard grew five different genotypes of the same algae species in the lab. They used a pipette to transfer 10,000 cells of each genotype and placed them in flasks at two different temperatures. The lower temperature treatment is one where corals and their algae are usually happy: 26 degrees Celsius. The higher temperature treatment is where coral’s relationship with algae starts to break down: 30 degrees Celsius. At that temperature, many corals lose their algae entirely, in a process called coral bleaching.

Casey and Richard measured two things – the total amount of photosynthesis and the total amount of respiration happening in each flask. They did this by tracking what happened to oxygen over time. When there is a lot of photosynthesis, oxygen goes up, and when there is a lot of respiration, oxygen goes down. Two conditions are best for the mutualism. First, a lot of photosynthesis means the algae produced more food that they can share with coral. Second, less respiration means the algae used less of the food for themselves and have more to share with the coral. In summary, when the algae is stressed it does less photosynthesis and more respiration, making it a worse trading partner for coral. The best algae partner is the genotype that can photosynthesize the most and respire the least. The net food available is how much of the food made through photosynthesis is available after subtracting the food used by respiration.

Featured scientists: Casey terHorst (he/him) and Richard Rachman (he/him)

from California State University Northridge

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = 8.9

Additional teacher resources related to this Data Nugget

- Here are some blog posts from Casey’s lab related to this topic.

- Visit Madeline van Oppen at the Australian Institute of Marine Science‘s website to learn more about assisted evolution in both corals and their algal symbionts.

- A couple YouTube videos demonstrating coral bleaching: