The Reading Level 1 activities are as follows:

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 1

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 1

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 1

The Reading Level 3 activities are as follows:

- Student activity, Graph Type A, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type B, Level 3

- Student activity, Graph Type C, Level 3

Teacher Resources:

Imagine you are a sea urchin. You’re a marine animal that attaches to hard surfaces for stability. You are covered in spikes to protect you from predators. You eat giant kelp – a type of seaweed. You prefer temperate water, typically between 5 to 16°C. But you’ve noticed that some days the ocean around you feels too hot.

These periods of unusual warming in the ocean are called marine heatwaves. During marine heatwaves, water gets 2-3 degrees hotter than normal. That might not sound like much, but for an urchin, it is a lot. The ocean’s temperature is normally very consistent, so urchins are used to a small range of temperatures. Urchins are cold-blooded. This means they can’t control their own body temperature and rely on the water around them. Whatever temperature the ocean water is, they are too!

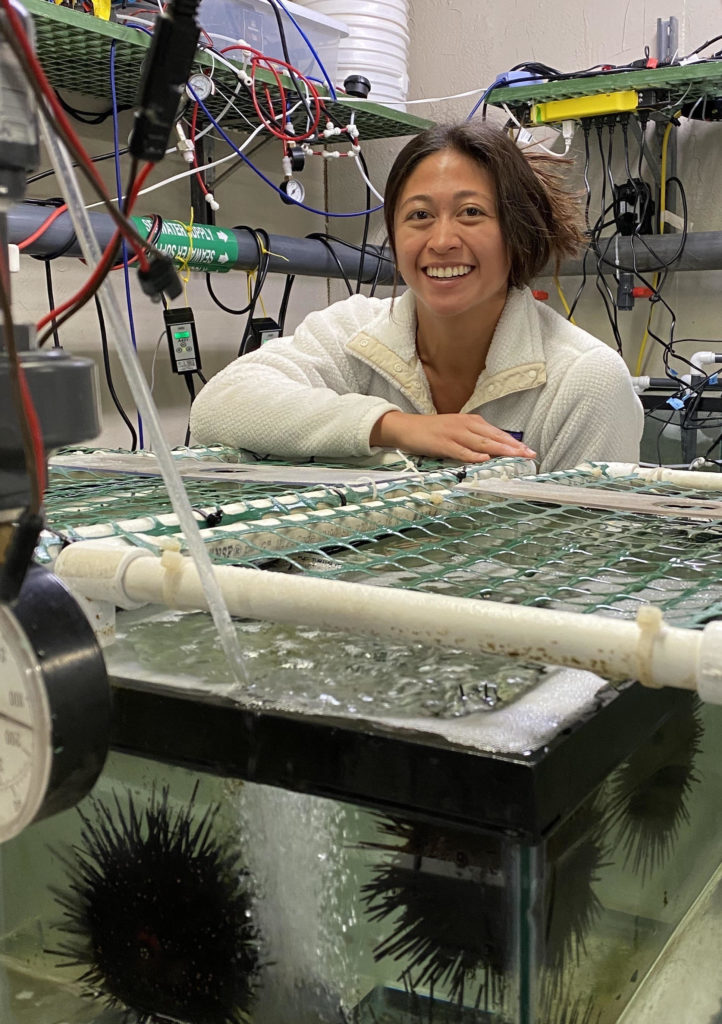

Erin is a scientist who studies how environmental changes, like temperature, affect organisms. Erin first got excited about urchins when she interned with a research lab. When she started graduate school, she learned more about their biology and started to ask questions about how urchins would react to marine heatwaves. Hot water can speed up animals’ metabolisms, making them move and eat more. However, warmer temperatures can also cause stress, potentially causing urchins to be clumsier and confused.

One summer, two science teachers, Emily and Traci, came to California to work in the same lab as Erin. Emily and Traci wanted to do science research so they can share their experience with their students. As a team, they decided to test whether marine heat waves could be stressing urchins by looking at a simple behavior that they could easily measure. Healthy urchins have a righting instinct to flip over to orient themselves “the right way” using their sticky tube feet.

The research team predicted that urchins would be slower to right themselves in warmer temperatures. However, they also thought the response could depend on the temperature the urchins were used to living in. If the urchins had been acclimated to higher temperatures, they might not be as strongly affected by the heatwaves.

Together, Erin, Emily, and Traci took 20 urchins into her lab and split them into 2 groups. Ten were kept at 15°C, the ocean’s normal temperature in summer. The other ten were kept at 18°C, a marine heatwave temperature. They let the urchins acclimate to these temperatures for 2 weeks. They tested how long it took each urchin to right itself after being flipped over. They did this at three temperatures for each urchin: 15°C (normal ocean), 18°C (heatwave), and 21°C (extreme heatwave). They worked together to test the urchins three times at each temperature to get three replicates. Then they calculated the average of each urchin’s responses.

Featured scientists: Erin de Leon Sanchez (she/her) from University of California – Santa Barbara, Emily Chittick (she/her), and Traci Kennedy (she/her) from Milwaukee Public Schools.

Flesch–Kincaid Reading Grade Level = The Content Level 3 activity has a score of 7.9 ; the Level 1 has a score of 5.9

Additional teacher resources related to this Data Nugget include:

- Here is a video of a parrotfish finding and eating an urchin. Show this video to emphasize how important it is for urchins to be able to right themselves!