Below, you will find a table of all the Data Nugget activities. Click on the Title to open a page displaying the teacher guide, student activities, grading rubric, and associated resources. The table can be sorted using the arrows located next to each column header. It can also be searched by content area using the search bar, located to the top right of the table.

| Title | Keywords | Summary | Content Level | Study Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

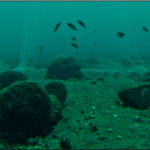

| Won’t you be my urchin? | coral reef, herbivory, marine, sea urchin, water, animals, competition | Corals are the most important reef animals since they build the reef for all of the other animals to live in. But corals only like to live in certain places. In particular they hate living near algae because the algae and coral compete for the space they both need to grow. Perhaps if there are more vegetarians, like urchins, eating algae on the reef then corals would have less competition and more space to grow. | 1 | Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, Texas |

| Do urchins flip out in hot water? | animals, climate change, marine, heatwaves, urchins, behavior, invertebrates, environmental change | Periods of unusual warming in the ocean are called marine heatwaves. During marine heatwaves, water gets 2-3 degrees hotter than normal. That might not sound like much, but for an urchin, it is a lot. The research team decided to test whether marine heat waves could be stressing urchins by looking at a simple behavior that they could easily measure - how long it takes urchins to flip back over. | 1 & 3 | University of California - Santa Barbara |

| Coral bleaching and climate change | climate change, coral reef, marine, mutualism, temperature, animals, algae, adaptation, evolution | Corals are animals that build coral reefs. They look brown and green because they have small plants, called algae, that live inside them. The coral animal and the algae work together to produce food so that corals can grow big. When the water gets too warm, sometimes the coral and algae can no longer work together. The algae leave and the corals turn white, called coral bleaching. Scientists want to study coral bleaching so they can protect corals and the reefs that provide a home for so many different species. | 1 | Florida Keys, Florida |

| Too hot to help? Friendship in a changing climate | mutualism, algae, coral, genotype, photosynthesis, respiration, climate change | Coral and certain types of algae form a mutualism. However, climate change is causing warmer ocean temperatures that stress the relationship. Casey set out to test if different algae genotypes were capable of being better mutualists under warm temperatures. If he could identify these genotypes, then maybe that could help protect coral in the future. | 3 | California State University - Northridge |

| Corals in a strange place | adaptation, coral reef, mangrove, morphology | When you picture coral, you might imagine beautiful reef structures with clear water and colorful corals and fishes. But, there are actually corals that live in other habitats as well! Does the same species of coral look different depending on where it lives? | 2 | Belize |

| Raising Nemo: Parental care in the clown anemonefish | animals, behavior, coral reef, ecology, fish, marine, mating, tradeoff, plasticity | Offspring in many animal species rely on parental care; the more time and energy parents invest in their young, the more likely it is that their offspring will survive. However, parental care is costly for the parents. The more time spent on care, the less time they have to find food or care for themselves. In the clown anemonefish, the amount of food available may impact parental care behaviors. When there is food freely available in the environment, are parents able to spend more time caring for their young? | 3 | Boston University, Massachusetts |

| Buried seeds, buried treasure | germination, long-term, plants, seed bank, seed viability, agriculture | Over 100 years ago, a scientist named William J. Beal had a question: how long do seeds survive underground? He started an experiment by filling 20 bottles with seeds from 50 plant species, buried them on campus, and creating a map to find them in the future. This map have been passed down from scientist generation to generation. The most recent bottle was dug up in 2021, and scientists tested how many seeds were still able to germinate after 142 years underground. | 2 | Michigan State University |

| Blinking out? | agriculture, insects, population, biodiversity, ecology | Many people have fond memories of watching fireflies blink across open fields and collecting them in jars as children. This is one of the reasons why fireflies are a beloved insect species. However, there is concern that their populations are in decline. Scientists turned to the longest-running study of fireflies known to science to see if this is the case! | 2 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Little butterflies on the prairie | animals, ecology, long-term, butterflies | Many farmers are concerned with growing our food while still protecting habitat wildlife. They want to know - how can we grow food for ourselves while still providing good habitat for other species? Prairie strips are a new idea that might help both farmers and the environment. These strips are small areas of prairie that can be added to farm fields. They look like rows of flowers and grasses within a field. They create habitat for many species, like butterflies, birds, ants, and even microscopic fungi and bacteria! | 2 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| The prairie burns with desire | ecology, prairie, plants, fire ecology, human impact, reproduction, land management | Fire plays a crucial role for prairie habitats across North America. Stuart became interested in learning more about how fire affects the reproduction of native prairie plants. He knew that Echinacea plants grow in many places, but they have a hard time making seeds. He looked at a long-term dataset to see whether fire might help Echinacea by getting plants on the same schedule to make flowers at the same time, bringing neighbors closer to each other and making it easier to be pollinated. | 3 | Staffanson Prairie Preserve, Minnesota |

| A burning question | biodiversity, canopy, ecology, fire ecology, forest, human impact, keystone species, land management, natural resources | Fire is part of the natural history of oak forests. They are adapted to recover quickly and they actually can benefit from fire. This is important for land managers who want to encourage the health of oak forests. Ellen and John wanted to know if there were more plant species in oak forests that had prescribed fires so they looked at a long-term dataset to find patterns in biodiversity. | 2 | Madison School Forest, Wisconsin |

| What grows when the forest goes? | fire, forest, invasive species, long-term, plants | The H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest in Oregon is a long-term research site where scientists study how ecosystems respond to disturbances like wildfire. After a major fire in 2023, biology teacher Matt and scientist Joe investigated how native and invasive plants recover from fires of varying severity. Using data from a 2020 fire, they analyzed plant communities to see if invasive species recovered more quickly than native ones. | 2 | HJ Andrews Experimental Forest LTER |

| Fertilizer and fire change microbes in prairie soil | biodiversity, diversity, grassland, microbes, plants, prairie, soil, agriculture, fire ecology | Prairies grow where three environmental conditions come together – a variable climate, frequent fires, and large herbivores roaming the landscape. However, prairies are experiencing many changes. For example, people now work to prevent fires, which allows forest species take over. In addition, land previously covered in prairie is now being used for agriculture. How do these changes affect the plants, animals, and microbial communities that inhabit prairies? | 4 | Konza Prairie Biological Station, Kansas |

| Does more rain make healthy bison babies? | animals, ecology, keystone species, plants, prairie, precipitation, agriculture | The North American Bison is an important species for the prairie ecosystem. Bison affect the health of the prairie in many ways, and are also affected by the prairie as well. Each year when calves are born, scientists go out and determine their health by weighing them. This long-term dataset can be used to figure out whether environmental conditions from the previous year affect the health of the calves born in the current year. | 2 | Konza Prairie Biological Station, Kansas |

| Bear Necessities: A genetic panel for bear identification | Animals, DNA, Genetics, Conservation | As human development encroaches on bear habitats, scientists like Isabella are using genetic tools to track individual bears and understand population structures for better conservation. By analyzing DNA from 350 bears, she identified genetic patterns linked to locations in North Carolina and is now using this information to trace the origins of a rescued baby bear named Murray. | 4 | North Carolina State University |

| City parks: wildlife islands in a sea of cement | animals, biodiversity, ecology, urban, island biogeography, parks | It's tempting to think that wild places are only somewhere "out there", far away from humans and cities. However, as more and more people move into cities, they are quickly becoming the main place where many people experience nature and interact with wildlife. A camera-trapping project in the Cleveland Metroparks reveals a vast urban wilderness that is home to countless wild creatures living among us. | 3 | Cleveland Metroparks, Ohio |

| Candid camera: capturing the secret lives of carnivores | animals, biodiversity, carnivores, ecology, island biogeography | Carnivores captivate people’s interest for many reasons – they are charismatic, stealthy, and can be dangerous. Not only are they fascinating, they’re also ecologically important. Carnivores help keep prey populations in balance. While they are important, they are also difficult to monitor. | 3 | Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, Wisconsin |

| Picky eaters: dissecting poo to examine moose diets | animal behavior, animals, ecology, foraging, herbivory, national park, predator-prey | Since wolves have disappeared from Isle Royale, moose populations have exploded. Moose are important herbivores, and with so many on the island they are having strong impacts on the island's plant communities. Do moose just eat any plant they find, or do they have a preference for certain types? | 3 | Isle Royale National Park, Michigan |

| Guppies on the move | animals, aquatics, behavior, ecology, genetics, migration, movement, tropics | Animal parents often choose where to have their offspring in the place that will give them the best chance at success. They look for places that have plentiful food, low risk of predation, and good climate. Why, then do animals sometimes move away from the place they are born? | 2 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Deadly windows | animals, behavior, birds, environmental, urban | Glass makes for a great windowpane because you can see right through it. However, this makes windows very dangerous for birds. Many birds die from window collisions in urban areas. In North America window collisions kill up to 1 billion birds every year! Perhaps local urban birds are able to learn the locations of windows and avoid collisions. By comparing window collisions by local birds to those of migrant birds just passing through, we can determine if local birds have learned to deal with this challenge. | 2 | Virginia Zoological Park, Virginia |

| Bringing back the Trumpeter Swan | animals, biodiversity, birds, ecology, environmental, restoration | Trumpeter swans are the biggest native waterfowl species in North America. At one time they were found across North America, but by 1935 there were only 69 known individuals in the continental U.S.! In the 1980s, many biologists came together to create a Trumpeter Swan reintroduction plan. Since then the North American Trumpeter Swan survey has been conducted to measure swan populations and determine whether this species is recovering. | 3 | Kellogg Bird Sanctuary, Michigan |

| The birds of Hubbard Brook, Part I | animals, biodiversity, birds, climate change, succession, disturbance, ecology | Avian ecologists at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest have been monitoring bird populations for over 50 years. The data collected during this time is one of the longest bird studies ever conducted! What can we learn from this long-term data set? Are bird populations remaining stable over time? | 2 | Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, New Hampshire |

| The birds of Hubbard Brook, Part II | animals, biodiversity, birds, climate change, succession, disturbance, ecology, habitat | Hubbard Brook was heavily logged and disturbed in the early 1900s. When logging ended in 1915, trees began to grow back. The forest then went through secondary succession, which refers to the naturally occurring changes in forest structure that happen as a forest ages after it has been cut or otherwise disturbed. Can these changes in habitat availability, due to succession, explain why the number of birds are declining at Hubbard Brook? Are all bird species responding succession in the same way? | 3 | Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, New Hampshire |

| Trees and bushes, home sweet home for warblers | animals, biodiversity, birds, disturbance, ecology, environmental, habitat | Andrews Forest is a long-term ecological research site where there have been manipulations of timber harvest and forest re-growth. This history has large impacts on the bird habitats found in an area. Each year since 2009, scientists have gone out and measured bird populations and habitat types. Two species of warbler with very different habitat preferences can give insight into how birds are responding to these disturbances. | 4 | HJ Andrews Experimental Forest, Oregon |

| Is chocolate for the birds? | agriculture, animals, birds, biodiversity, ecology, rainforest, succession, habitat | Humans invented agriculture 9,000 years ago, and today it covers 40% of Earth’s land surface. To grow our crops, native plants are often removed, causing the loss of animals that relied on these native plants for habitat. However, sometimes animals can use crop species for food and shelter. For example, the cacao tree may provide habitat for bird species in the rainforests of Costa Rica. Will the abundance and types of birds differ in cacao plantations, compared to native rainforests? | 2 | Limón Province, Costa Rica |

| Feral chickens fly the coop | adaptation, animals, behavior, birds, ecology, evolution, invasive species, mating, heredity, genetics | Sometimes domesticated animals escape captivity and interbreed with closely related wild relatives. Their hybrid offspring have some traits from the wild parent, and some from the domestic parent. Traits that help hybrids survive and reproduce will be favored by natural selection. On the island of Kauai, domestic chickens escaped and recently interbred with wild Red Junglefowl to produce a hybrid population. Over time, will the hybrids on Kauai evolve to be more like chickens, or more like Red Junglefowl? | 3 | Kauai, Hawaii |

| Sexy smells | adaptation, animal behavior, animals, birds, mating, evolution, sexual selection | Animals collect information about each other and the rest of the world using multiple senses, including sight, sound, and smell. They use this information to decide what to eat, where to live, and who to pick as a mate. Many male birds have brightly colored feathers and ornaments that are attractive to females. Visual signals like these ornaments have been studied a lot in birds, but birds may be able to determine the quality of a potential mate using other senses as well, such as their smell! | 2 | Mountain Lake Biological Station, Virginia |

| Finding Mr. Right | adaptation, animals, behavior, biodiversity, birds, evolution, genes, mating, local adaptation | Mountain chickadees are small birds that live in the mountains. To deal with living in a harsh environment during the winter, mountain chickadees store large amounts of food throughout the forest. Compared to populations at lower elevations, birds from higher elevations are smarter and have better spatial memory, helping them better find stored food. Smarter females from high elevations may be contributing to local adaptation by preferring to breed with males from their own population. | 4 | University of Nevada Reno & Sagehen Experimental Forest |

| Spiders under the influence | animals, invertebrates, habitat, chemical pollution, aquatic, streams | People use pharmaceutical drugs, personal care products, and other chemicals on a daily basis. Often, they get washed down our drains and end up in local waterways. Chris knew that many types of spiders live near streams and are exposed to toxins through the prey they eat. Chris wanted to compare effects of the chemicals on spiders in rural and urban environments. By comparing spider webs in these two habitats, they could see how different the webs are and infer how many chemicals are in the waterways. | 2 | Baltimore Ecosystem Study LTER |

| Trees and the city | biodiversity, ecology, environmental justice, social demographics, urban | Trees provide important benefits, such as beauty and shade. The number and types of tree species that are planted in a neighborhood can increase the benefits received from trees in urban areas. Based on her own observations, Adrienne started conversations with her colleagues about differences in urban landscapes. They conducted a study to see how social demographics of neighborhoods may be related to tree species richness and tree cover. | 3 | Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota |

| Do you feel the urban heat? | urban, climate change, extreme heat, environmental justice, human impacts, socioeconomic, sensors | Record-breaking temperatures climb higher every year, and Florida is no exception. These extreme temperatures affect organisms of all types, including humans. Irvin wanted to see how much the heat varies across Miami and compare it to the sensor at the airport that is used to issue heat warnings. He focused on sites where people gather outside - bus stops. He also chose sites that varied in shade coverage to see how temperatures fluctuate in different environments. | 3 | Miami, Florida International University |

| Salty sediments? What bacteria have to say about chloride pollution | bacteria, chemistry, disturbance, environmental, microbes, pollution, salt, urban, water | In snowy climates, salt is applied to roads to help keep them safe during the winter. When the snow melts, salt makes its way into local rivers. Halophiles, or bacteria that thrive in salty conditions, might be a good indicator of how much salt is in a particular waterway, telling scientists when certain areas have become too polluted with salt. | 3 | Southeastern Wisconsin |

| A tail of two scorpions | animal behavior, animals, predation | Species rely on a variety of methods to defend against predators, including camouflage, speedy escape, or retreating to the safety of a shelter. Other animals, such as scorpions, have painful venomous stings. Scientists wanted to know whether the pain of a scorpion sting was enough to deter predators, like the grasshopper mouse. | 2 | Santa Rita Mountains, Arizona |

| Why are butterfly wings colorful? | adaptation, animals, insects, models, predation | Big wings allow butterflies to fly everywhere with ease. But you may wonder, why are the wings of some species so brightly colored? The red postman butterfly lives in rainforests in Mexico, Central America, and South America. The color pattern on its wing is usually a mix of red, yellow, and black. These bright colors may warn birds and other predators that they would not make a tasty meal. Another potential reason for butterflies to have bright colors and dramatic patterns is to attract mates. | 3 | La Selva Tropical Biological Station, Sarapiquí, Costa Rica |

| To bee or not to bee aggressive | animals, behavior, genes, insects, tradeoff, plasticity, aggression | Honey bees turn nectar from flowers into honey. Honey serves as an energy-rich food source for the colony. It also makes hives a target for break-ins by animals that want to steal it. Bees need to aggressively defend their honey when the hive is threatened. They also need to ensure they don't waste energy on unnecessary behaviors when the threat level is low. One way bees might match their aggressiveness to the threat level in the environment is learning from adults when they are young. | 3 | University of Kentucky, Kentucky |

| Ant wars! | aggression, animals, behavior, competition, insects | Neighboring colonies of pavement ants often compete for food, leading to tension. If an ant finds a non-nestmate, it organizes a large war against the nearby colony. This results in huge sidewalk battles that can include thousands of ants fighting for up to 12 hours! Scientists wanted to know, what are the factors that lead to war? | 3 | University of Colorado-Denver and University of South Dakota |

| CSI: Crime Solving Insects | animals, insects, parasitism | You might think maggots (blow fly larvae) are gross, but without their help in decomposition we would all trip over dead bodies every time we went outside! Forensic entomologists also use these amazing insects to help solve crimes. Blow flies oviposit on dead bodies; the age of the maggots helps scientists determine how long ago a body died. Scientists noticed parasitic wasps were also present at some bodies. Might these wasps delay blow fly oviposition and interfere with scientists' estimates of time of death? | 3 | Pierce Cedar Creek Institute, Michigan & Valparaiso University, Indiana |

| Shooting the poop | adaptation, animal behavior, animals, insects, predation | Caterpillars are a great source of food for many species. The silver-spotted skipper caterpillar has a variety of defense strategies against predators, including building leaf shelters for protection. This caterpillar was also discovered to “shoot its poop”, sometimes launching it over 1.5m! Might this very strange behavior serve as some sort of defense against predators? | 2 | Georgetown University, Washington DC |

| How the cricket lost its song, Part I | adaptation, animal behavior, animals, evolution, mating, parasitism, rapid evolution | Pacific field crickets live on several Hawaiian Islands, including Kauai. Male field crickets make a loud, long-distance song to help females find them, and then switch to a quiet courtship song once a female comes in close. One summer scientists noticed that the crickets on the island were unusually quiet. Back in the lab they saw males that had lost their specialized wing structures used to produce song! Why did these males lose their wing structures? | 3 | Kauai Agricultural Research Center - Kapaa, Hawaii |

| How the cricket lost its song, Part II | adaptation, animal behavior, animals, evolution, mating, parasitism, rapid evolution | Without their song, how are flatwing crickets able to attract females? In some other animals species, males use an alternative to singing, called satellite behavior. Satellite males hang out near a singing male and attempt to mate with females who have been attracted by the song. Perhaps the satellite behavior gives flatwing males the opportunity to mate with females who were attracted to the few singing males left on Kauai. | 3 | Kauai Agricultural Research Center - Kapaa, Hawaii |

| Purring crickets: The evolution of a new cricket song | adaptation, animal behavior, animals, evolution, mating, parasitism, rapid evolution | About twenty years ago, scientists discovered male Pacific field crickets in several spots in Hawaii had stopped making songs due to selection from a parasitoid fly that uses the songs to locate their hosts. One summer, scientists heard what sounded like a purring cat, but there was no cat in sight. This sound was coming from crickets, and was unlike anything ever observed before. Could it be the beginning of evolution of a novel mating signal? | 3 | Kauai Agricultural Research Center - Kapaa, Hawaii |

| Beetle battles | adaptation, animals, behavior, competition, evolution, insects, mating | Male animals spend a lot of time and energy trying to attract females. They may fight with other males or court females directly. Is there one trait that is both good for fighting males and attracting females? In the horned dung beetle, males have to fight with other males for space in underground tunnels where females mate and lay their eggs. Males also attract females by tapping on their backs. Males that are stronger may potentially be better at both defending tunnels and at attracting females by tapping. | 2 | Perth, Australia |

| Tree-killing beetles | animals, biodiversity, disturbance, ecology, environmental, insects, plants | A beetle the size of a grain of rice seems insignificant compared to a vast forest. However, during outbreaks the number of mountain pine beetles can skyrocket, leading to the death of many trees. Recent outbreaks of mountain pine beetles killed millions of acres of lodgepole pine trees across western North America. Widespread tree death caused by mountain pine beetles can impact human safety, wildfires, nearby streamflow, and habitat for wildlife. | 2 | Colorado State University, Colorado |

| Mowing for monarchs, Part I | animals, behavior, biodiversity, disturbance, ecology, plants, insects | During the spring and summer months, monarch butterflies lay their eggs on milkweed plants. Milkweed plays an important role in the monarch butterfly’s life cycle. When milkweed is cut at certain times of the year new shoots grow, which are softer and easier for caterpillars to eat. Scientists set out to see if mowing milkweed plants could help boost struggling monarch populations. | 2 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Mowing for monarchs, Part II | animals, behavior, biodiversity, disturbance, ecology, plants, insects, predation | When the scientists mowed down milkweed plants for their experiment, they changed more than the age of the milkweed plants. They also removed other plant species in the background community. Perhaps the patterns they were seeing were driven not by milkweed age, but by eliminating predators from the patches they mowed. | 2 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| How milkweed plants defend against monarch butterflies | herbivory, evolution, coevolution, plants, insects, ecology | For millions of years, monarch butterflies have been antagonizing milkweed plants. Although adult monarchs drink nectar from flowers, their caterpillars only eat milkweed leaves, which harms the plants. The only food for monarchs is milkweed leaves, meaning they have evolved to be highly specialized, picky eaters. But their food is not a passive victim. Like most other plants, milkweeds fight back with defenses against herbivory. Which defensive traits are helping in the fight against herbivory? | 3 | Cornell University |

| Does the heat turn caterpillars into cannibals? | animal behavior, insect, virus, disease ecology, temperature, cannibalism, caterpillar | When Kale started graduate school, they joined a lab that studies how climate change affects the spread of disease in fall armyworms, a type of caterpillar. Fall armyworms can get infected with a special type of virus and it can be spread through cannibalism. Do warmer temperatures cause caterpillars to be hungrier, leading to more cannibalism and disease spread? | 3 | Lousiana State University, Louisiana |

| Where to find the hungry, hungry herbivores | herbivory, plants, insects, ecology | When travelling to warm, tropical places you are exposed to greater risk of diseases. The same pattern of risk is true for other species like plants grown for food; crops in warm places have more problems with pests than those in colder areas. Does this pattern hold for plants in the wild as well? | 2 | Michigan State University |

| Are plants more toxic in the tropics? | herbivory, diversity, plants, insects, ecology, adaptation | Long before chemists learned how to make medicines in the laboratory, people found their medicines in plants. To this day, people still extract some medicinal drugs from plants. But, why do plants make these chemicals that are often so useful to people? Many of these chemicals are to reduce herbivory. Carina thought that this might differ by latitude, or distance from the Equator. Are tropical plants more toxic? | 3 | Michigan State University |

| Do insects prefer local or foreign foods? | herbivory, invasive species, plants, insects, enemy release, ecology | Insects that feed on plants, called herbivores, can have big effects on how plants grow. A plant with leaves eaten by herbivores will likely do worse than a plant that is not eaten. Herbivores may even determine how well an exotic plant does in its new habitat and whether it becomes invasive. Understanding what makes a species become invasive could help control invasions already underway, and prevent new ones in the future. | 2 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Do invasive species escape their enemies? | herbivory, invasive species, plants, insects, enemy release, ecology | Invasive species have been introduced by humans to a new area and negatively impact places they invade. Many things change for an invasive species when it is moved from one area to another. For example, a plant that is moved across oceans may not bring its enemies along for the ride. Now that the plant is in a new area with nothing to eat or infect it, the plant could potentially do very well and become invasive. | 2 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Testing the tolerance of invasive plants | ecology, herbivory, invasive species, plants, tolerance | People move species around the globe, and some of these species cause problems where they are introduced. What is it about these invasive species that makes them able to invade? Perhaps certain traits cause invasive species to be more troublesome than others. By studying trait differences between native and invasive populations of the same species, we can learn something about the causes of invasions. | 3 | McLaughlin Natural Reserve, California |

| Invasion meltdown | climate change, ecology, invasive species, plants, temperature | Humans are changing the earth in many ways, including adding greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere, which contributes to climate change, and introducing species around the globe, which can lead to invasive species. Scientists wanted to know, could climate change actually help invasive species? Because invasive species have already survived transport from one habitat to another, they may be species that are better able to handle change, such as temperature changes. | 3 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Springing forward | climate change, phenology, plants, temperature | What does climate change mean for flowering plants that rely on temperature cues to determine when it is time to flower? Scientists who study phenology, or the timing if life-history events in plants and animals, predict that with warming temperatures, plants will produce their flowers earlier and earlier each year. | 1 & 3 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Catching fish with sound | climate change, fish, ocean, sound | Climate change is warming our oceans, and scientists like Mei are studying how this affects marine food webs, especially small schooling fish that play a crucial role between predators and prey. As part of a long-term ecological research project in the Northeast U.S., Mei collects data using advanced sound technology to measure fish abundance, to build a clearer picture of how ocean ecosystems are changing over time, providing valuable information for fishers and resource managers preparing for the future. | 4 | Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Northeast U.S. Shelf LTER |

| The sound of seagrass | acoustics, sound, photosynthesis, marine, productivity, decibels, physics | Underwater seagrass meadows have high plant productivity, or growth, which could help offset the effects of climate change. Megan and Kevin are working with biologists to determine the value of applying sound-based methods to monitor photosynthesis in seagrass meadows. They wanted to see whether ambient sound levels were noticeably different during peak photosynthesis times. | 3 | Gulf of Mexico, Texas |

| Seagrass survival in a super salty lagoon | climate change, ecology, environmental, long-term, marine, plants, salinity | Unfortunately, seagrasses are disappearing worldwide. Seagrasses are sensitive to changes in their environment because they have particular conditions that they prefer. Kyle started working with Ken during graduate school and wanted to understand more about what environmental conditions, such as salinity, temperature, and light levels may have caused the decline they saw in manatee grass in Laguna Madre. | 3 | Laguna Madre, Gulf of Mexico, Texas |

| Lake Superior Rhythms | amplitude, aquatic, atmosphere, environmental, physics, student research, wave period, waves | In high school, Gena and Ali set out to learn about the geophysical forces acting on Lake Superior. They wanted to investigate why they would sometimes see such dramatic fluctuations in Lake Superior water levels. They learned that large lakes exhibit a phenomenon called a seiche (pronounced saysh) and they decided to investigate how often the water switched directions and how much the water level changed because of the seiche. | 2 | Bayfield, Wisconsin |

| The end of winter as we’ve known it? | climate change, ice cover, student research | Lake Superior plays a vital role in the lives of people who live and work on its shores, and therefore all sorts of data are recorded to help understand and take care of it. Forrest, a high school student, used data from archives to figure out if the ice season was getting shorter each winter in his home town. The length of the ice season is important because it frees the island residents from working around a ferry schedule, allowing them to drive on the ice to get to the mainland. | 3 | Madeline Island, Wisconsin |

| When a species can’t stand the heat | animals, climate change, disturbance, ecology, environmental, mating, temperature | Tuatara are a unique species of reptile found only in New Zealand. In this species, the temperature of the nest during egg development determines the sex of offspring. Warm nests lead to more males, and cool nests lead to more females. With warming temperatures due to climate change, scientists expect the sex ratio to become more and more unbalanced over time, with males making up more of the population. This could leave tuatara populations with too few females to sustain their numbers. | 3 | North Brother Island, New Zealand |

| What do trees know about rain? | climate change, dendrochronology, ecology, plants, precipitation, temperature, water | The typical climate of arid northwest Australia consists of long drought periods with a few very wet years sprinkled in. Scientists predict that climate change will cause these cycles to become more extreme – droughts will become longer and periods of rain will become wetter. When variability is the norm, how can scientists tell if the climate is changing and droughts and rain events today are more intense than what we've seen in the past? The answer to this challenge comes from trees! | 3 | Pilbara region, northwest Australia |

| Changing climates in the Rocky Mountains | citizen science, climate change, community science, ecology, environmental, plants | As the climate warms and precipitation changes, plants may have to move to survive. To figure out if species are moving, we need to know where they’ve lived in the past, and if climates are changing. One way that we can study both things is to use the Global Vegetation Project. The goal of this project is to curate a global database of plant photos that can be used by educators and students around the world. | 4 | Rocky Mountains, Wyoming |

| A window into a tree’s world | climate change, dendrochronology, ecology, plants, temperature | Scientists are very interested in learning how trees respond to rapidly warming temperatures. Luckily, trees offer us a window into their lives through their growth rings. Growth rings are found within the trunk, beneath the bark. These rings provide a long historical record, which can be used to study how trees respond to climate change. | 2 | Harvard Forest LTER, Massachusetts |

| CO2 and trees, too much of a good thing? | CO2, climate change, photosynthesis, plants, respiration, greenhouse gasses, trees, forests | Since the Industrial Revolution, rising carbon dioxide levels have warmed the planet, prompting scientists to explore how this affects forests. Kristina and Luca studied long-term tree growth and mortality data to understand whether climate change helps or harms trees. By measuring carbon gained through growth and lost through tree death, they calculated how much carbon the forest stores or releases each year. | 4 | Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute |

| Breathing in, Part I | climate change, photosynthesis, respiration, carbon | Photosynthesis is the process by which trees and other plants trap the sun’s energy within the molecular bonds of glucose. Tree growth pulls carbon out of the atmosphere and trees hold on to it for long periods of time. This process is known as carbon sequestration or carbon accumulation. Kristina and Susan decided they needed to work together to learn more about how carbon accumulation rates and how they differ across various types of forests found around the world. | 4 | Global |

| Breathing in, Part II | climate change, photosynthesis, respiration, carbon, climate model, precision | Like many other scientists, Susan and Kristina are concerned about global warming. Global warming is the well-documented rise of the temperature of Earth’s surface, oceans, and atmosphere. They wanted to make sure that those creating climate change policy have the most precise data available. They compared their ForC model, which predicts carbon accumulation based on forest regrowth across the glove, to a similar model the IPCC was using. | 4 | Global |

| Beetle, it’s cold outside! | animals, climate change, ectotherm, insects, temperature, snow | Many species rely on the snow for protection from the winter’s cold. The snow acts as an insulating blanket, covering the soil and keeping it from getting too cold. If temperatures get too hot in the winter, snow melts and leaves the soil uncovered for longer periods of time. This leads to the shocking pattern that warmer temperatures actually means the soil gets colder! How will species that rely on the snow, like lady beetles, respond to warmer temperatures due to climate change? | 2 | University of California, Berkeley |

| Benthic buddies | adaptation, animals, arctic, biodiversity, ecology, environmental, invertebrates, lagoons, marine | Arctic lagoons support a surprisingly wide range of marine organisms! Marine worms, snails, and clams live in the muddy sediment of these lagoons. Having a rich variety of benthic animals in these habitats supports fish, which migrate along the shoreline and eat these animals once the ice has left. Ken, Danny, and Kaylie are interested in learning more about how the extreme seasons of the High Arctic affect the marine life that lives there. | 2 | Beaufort Lagoon LTER site, Alaska |

| To reflect, or not to reflect, that is the question | albedo, Arctic, climate change, environmental, ice, temperature, water | Long-term observations of sea ice extent at the North Pole show it is declining, and fast! Why is this important? Sea ice has a higher albedo than sea water, meaning it reflects back more of the sun's energy. If Arctic albedo decreases, this might create a feedback and lead to even more warming. | 3 | University of Colorado, Boulder |

| The Arctic is melting – so what? | climate change, marine, models, temperature, water, weather, snow, albedo, Arctic | Think of the North Pole as one big ice cube – a vast sheet of ice, only a few meters thick, floating over the Arctic Ocean. With global warming, more sea ice is melting than ever before. If more ice melts in the summer than is formed in the winter, the Arctic Ocean will become ice-free. Scientists ran a climate model to determine whether this loss of sea ice could affect extreme weather in the northern hemisphere. | 4 | Arctic Ocean, North Pole |

| Eavesdropping on the ocean | acoustic ecology, physics, whales technology, mammals, marine biology, renewable energy, population, human impact | Winds that blow over the ocean are more consistent than on land, making offshore wind energy a potentially reliable renewable energy source. The construction of offshore windmills could impact whales. Scientists want to see whether it is possible to identify the best time of year for construction with the least disturbance to marine mammals. Acoustic ecology is a way to learn more about whales their presence in the proposed wind energy areas through sound. | 4 | Offshore by Morro Bay, California |

| When whale I sea you again? | climate change, marine, temperature, water, whales | People have hunted whales for over 5,000 years for their meat, oil, and blubber. Today, as populations are struggling to recover from whaling, humpback whales are faced with additional challenges due to climate change. Their main food source is krill, which are small crustaceans that live under sea ice. As sea ice disappears, the number of krill is getting lower and lower. Humpback whale population recovery may be limited because their main food source is threatened by ongoing ocean warming. | 4 | Western Antarctic Peninsula, Palmer Station LTER |

| Testing the waters for oyster farming | applied research, environmental, mariculture, marine, oceanography, oyster, salinity, chemistry | With so much coastline, Alaska has many opportunities for mariculture. Amanda is a marine researcher who wants to figure out which methods are most effective for oysters to grow near her. Because of the large amount of precipitation in Valdez, Alaska, she thought the water at the surface may not be salty enough for oysters to thrive. Along with her student, Jane, she monitored salinity levels and oyster growth at different depths and in two types of gear - lantern nets and surface baskets. | 2 | Prince William Sound College, Alaska |

| Growing kelp for community | environmental, growth, human impacts, kelp, mariculture, marine, photosynthesis, traditional knowledge | Recently, there has been a surge of interest in farming kelp at a larger scale along the Alaskan coast. Caitlin is a biologist who works for the Native Village of Eyak within the Prince William Sound of Alaska. The Tribe wants to start a kelp farm to provide a nutritious food source for its community. Follow along as Caitlin assesses the feasability of a kelp farm in the area. | 2 | Eyak and Cordova, Alaska |

| Can biochar improve crop yields? | agriculture, environmental, fertilization, plants, soil, water | Biochar is a pretty unique material. It is created when things burn without oxygen. Most biochar has lots of tiny spaces, or pores, that cause it to act like a hard sponge when it is in the soil. Due to these pores, the biochar can hold more water and nutrients than the soil can by itself. Adding biochar to the soil may help farmers grow more crops, especially in areas prone to drought where water is limited. | 3 | Colorado State University Agricultural Research and Development Center |

| Farms in the fight against climate change | Carbon, soil, LTER, climate change | Different farming practices affect the amount of carbon stored in soil, an important factor for soil health and climate change. Soil scientist Caro analyzed long-term data from a 30-year experiment at Kellogg Biological Station, comparing four land management types—including conventional farming, no-till, and cover crops—to see which ones best increase soil carbon. Her work helps identify practices that benefit both farmers and the planet. | 2 | University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the W. K. Kellogg Biological Station |

| A plant breeder’s quest to improve perennial grain | agriculture, genetics, artificial selection, DNA, phenotype, genotype, nucleotides, sequencing, Kernza® | Kernza® is a new grain crop that is similar to wheat. Kernza® breeders are working on improving the same traits that have already been improved in annual wheat, including larger seed size. Hannah wanted to see whether different genetic makeups (genotypes) lead to differences in seed size (phenotypes) so selecting individuals to breed becomes easier and costs are reduced. | 4 | University of Minnesota |

| Nitrate: Good for plants, bad for drinking water | agriculture, environmental, fertilization, nitrogen, soil, water, plants, human health, crops, Kernza® | Nitrate dissolves well in water. This helps make it an easy form of nitrogen for plants to use, but it can also end up in rivers and groundwater where it becomes harmful to human health. Most of the crops we grow are annual plants with shallow roots, but perhaps planting perennial crops can help take more nitrate from the soil before it reaches our groundwater. | 3 | University of Minnesota |

| Collaborative cropping: Can plants help each other grow? | agriculture, environmental, plants, crops, Kernza® | Most of the crops grown on farms in the United States are annual plants, like corn, soybeans, and wheat. However, there may be potential benefits of perennial plants that could increase sustainability. One strategy to improve field conditions for perennial crops and to increase yield could be to plant legumes alongside them. | 3 | University of Minnesota |

| A difficult drought | fermentation, ethanol, agriculture, biofuels, climate change, plants, carbon | Biofuels are made from plants that are growing today, and are being considered as an alternative to fossil fuels. To become biofuels, plants need to go through a series of chemical and physical processes that transform the sugars into ethanol. Scientists are interested in seeing how yeast’s ability to transform sugar into fuel is affected by environmental conditions in fields, such as droughts. | 2 | University Wisconsin-Madison, GLBRC, Kellogg Biological Station & |

| Growing energy: comparing biofuel crop biomass | agriculture, biofuels, climate change, fertilization, plants | Corn is one of the best crops for producing biomass for fossil fuels, however it is an annual and needs very fertile soil. To grow corn, farmers add a lot of chemical fertilizers and pesticides to their fields. Other crops, like switchgrass, prairie, poplar trees, and Miscanthus grass are perennials and require fewer fertilizers and pesticides to grow. If perennials can produce high levels of biomass with low inputs, perhaps they could produce more biomass than corn under certain low nutrient conditions. | 3 | GLBRC, Kellogg Biological Station & University Wisconsin-Madison |

| Fertilizing biofuels may cause release of greenhouse gasses | agriculture, biofuels, climate change, fertilization, greenhouse gasses, nitrogen, plants | One way to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases we release into the atmosphere could be to grow our fuel instead of drilling for it. Unlike fossil fuels that can only release CO2, biofuels remove CO2 from the atmosphere as they grow and photosynthesize, potentially balancing the CO2 released when they are burned for fuel. However, the plants we grow for biofuels don’t necessarily absorb all greenhouse gas that is released during the process of growing them on farms and converting them into fuels. | 3 | GLBRC, Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| The ground has gas! | agriculture, climate change, temperature, greenhouse gasses, nitrogen, plants, chemistry | Nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide are responsible for much of the warming of the global average temperature that is causing climate change. Sometimes soils give off, or emit, these greenhouse gases into the earth’s atmosphere, adding to climate change. Currently scientists figuring out what causes differences in how much of each type of greenhouse gas soils emit. | 3 | GLBRC, Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Are forests helping in the fight against climate change? | climate change, ecology, environmental, greenhouse gasses, photosynthesis, plants | In the 1990s, scientists began to wonder what role forests were having in the exchange of carbon in and out of the atmosphere. Were forests overall storing carbon (carbon sink), or releasing it (carbon source)? To test this, they built large metal towers that stand taller than the forest trees around them and use sensors to measure the speed, direction, and CO2 concentration of each puff of air that passes by. These long term measurements can tell us whether forests help in the fight against climate change. | 3 | Harvard Forest LTER, Massachusetts |

| Sink or source? How grazing geese impact the carbon cycle | carbon cycle, Arctic, wetlands, primary production, photosynthesis, respiration, climate change, birds, ecology | When geese graze on wetland plants, they remove plant matter, potentially decreasing the amount of carbon dioxide, or CO2, that is released during photosynthesis. This is important because it could change whether this ecosystem is a carbon sink or a carbon source. We want ecosystems to be carbon sinks because then they keep CO2 out of the atmosphere, where it contributes to global warming. | 3 | Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, Alaska |

| Poop, poop, goose! | wetlands, Arctic, carbon cycle, climate change, disturbance, ecology, environmental, greenhouse gasses, birds | Each spring, millions of birds return to the Y-K Delta to breed. With all these geese coming together in one area, they create quite a mess – they drop tons of poop onto the soil. So much poop in fact, that scientists wonder whether poop from this area in Alaska could have a global impact! | 3 | Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, Alaska |

| Salmonberries in our future | Arctic, wetlands, climate change, ecology, disturbance, water, marine | In western Alaska, salmonberries are a vital food source and cultural tradition for Yup’ik and Cup’ik communities, but climate change threatens their growth. Ecologists are working with local communities to study how these changes affect berry plants, since shifts in plant survival and abundance will directly impact food security and cultural practices. | 2 | Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, Alaska |

| Stormy shorelines | climate change, disturbance, ecology, environmental, growth, human impact, plants, water, wetlands | In recent years, coastal flooding has become more common near Chevak. Protective sea ice melts earlier each year. Storm surges and rising sea levels now push salty water further inland. These flooding events increase erosion, damage property, and alter the delicate balance of wetland and tundra ecosystems. Scientists Karen, Kathy, and Josh wanted to know how these changes were affecting local plants, especially those that are culturally important in the area! | 3 | Chevak, Alaska |

| Going underground to investigate carbon locked in soils | climate change, ecology, environmental, greenhouse gasses, soil carbon, microbes, chemistry, agriculture | Soil is an important part of the carbon cycle because it traps carbon, keeping it out of the atmosphere and locked underground. Carbon enters the soil when plants and animals die, and their organic matter is decomposed by soil bacteria and fungi. Climate affects rates of decomposition, and therefore may affect how much carbon becomes stable and attached to minerals in the soil, feeding back to affect climate change. | 3 | Indiana University |

| Microbes facing tough times | drought, enzyme, microbes, mutualist, agriculture | As the climate changes, Michigan is expected to experience more drought. Scientists are looking into how crop mutualistic interactions with microbes may help them withstand drought periods. First they need to know how microbes are impacted by different carbon and drought conditions. | 3 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| The carbon stored in mangrove soils | carbon, climate change, disturbance, ecology, nutrients, greenhouse gasses, mangrove, plants | Mangroves are globally important for many reasons. They form dense forested wetlands that protect the coast from erosion and provide critical habitat for many animals. Mangrove forests also help in the fight against climate change by storing carbon in their soils. The balance between how much carbon is added to the soils and how much is released might be dependent on a variety of factors, including tree size and amount of disturbance to the site. | 2 | Biscayne National Park, Florida Everglades |

| Mangroves on the move | climate change, ecology, environmental, fertilization, nitrogen, nutrients, phosphorus, plants, mangrove | One day out in the saltmarsh, scientists noticed something strange. A mangrove shrub was growing in a place they had not been seen before! Are the fertilizers washing into the saltmarsh from nearby urban areas responsible for this shocking discovery? | 2 | Guana-Tolomato-Matanzas National Estuarine Research Reserve, Florida |

| Which tundra plants will win the climate change race? | climate change, nutrients, long-term data, competition, plants, ecology | While you might think of the arctic tundra as a blanket of snow and polar bears, this vast landscape supports a diversity of unique plant and animal species. Climate change is altering the arctic environment. With warmer seasons and fewer days with snow covering the ground, soils are thawing more deeply and becoming more nutrient-rich. With more nutrients available, will some plant species be able to outcompete other species by growing taller and making more leaves than other plant species? | 3 | Toolik Field Station, Alaska |

| Streams as sensors: Arctic watersheds as indicators of change | climate change, ecology, environmental, carbon, nitrogen, permafrost | As the world warms from climate change, the Alaskan Arctic is heating up. This is causing permafrost, or the frozen underground layer of rock and ice, to melt. When permafrost melts, plant material that has been stored for thousands of years begins to decay, releasing carbon and nitrogen from the system. Ecologists can act like “ecosystem accountants” measuring the balance of material that goes into and out of these systems. | 3 | Toolik Field Station, Alaska |

| Limit by limit: Nutrients control algal growth in Arctic streams | climate change, ecology, environmental, nitrogen, nutrients, phosphorus | Aquatic algae, a type of microbe that live in the water, need to take in nutrients from their surroundings for growth. Two important nutrients for algal growth are nitrogen (N) and phosphorous (P). Climate change may be altering which nutrients are limiting to algae, changing food webs in the ecosystem. | 3 | Toolik Field Station, Alaska |

| Cheaters in nature – when is a mutualism not a mutualism? | evolution, legume, plants, mutualism, parasitism, rhizobia, nitrogen, fertilization, agriculture | Mutualisms are a special type of relationship in nature where two species work together and both benefit. This cooperation should lead to each partner species doing better when the other is around – without their mutualist partner, the species will have a harder time acquiring resources. But what happens when one partner cheats and takes more than it gives? | 4 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Fair traders or freeloaders? | evolution, legume, plants, mutualism, rhizobia, nitrogen, fertilization, agriculture | One example of a mutualism is the relationship between a type of bacteria, rhizobia, and plants like peas, beans, soybeans, and clover. Rhizobia live in bumps on the plant roots, where they trade their nitrogen for sugar from the plants. Rhizobia turn nitrogen from the air into a form that plants can use. Under some conditions, this mutualism could break down, for example, if one of the traded resources is very abundant in the environment. | 3 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Does a partner in crime make it easier to invade? | legume, plants, mutualism, rhizobia, invasive species, soil | Invasive plants are species that have been transported by humans from one location to another, and grow and spread quickly compared to other plants. Mutualisms can affect what happens when a plant species is moved somewhere it hasn’t been before. For invasive legumes with rhizobia mutualists, there is a chance that the rhizobia will not be transported with it and the plant will have to form new relationships with rhizobia in the new location. | 3 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Fast weeds in farmer’s fields | adaptation, agriculture, evolution, plants, heredity, genetics | Weeds in agricultural fields cost farmers $28 billion per year in just the United States alone. One of the world’s worst weeds is weedy radish, which evolved from native radish not very long ago. While weedy radish is able to take over agricultural fields, native radish cannot. What causes this difference? Perhaps it could be due to the weedy radish’s ability to flower quickly and make seeds before crops are harvested. | 2 | Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Reconstructing the behaviour of ancient animals | anatomy, animals, behavior, form and function, fossils, nocturnal, paleobiology, primate | Holly specializes in using fossils to paint a picture of the lifestyles of ancient animals. She uses the shape, structure, damage patterns, and burial poses of bones, and compares them to modern bones. By using what we know about living species, Holly can reconstruct the life and death of ancient organisms. Holly compared a primate skull fossil to its living relatives to see if she can determine if the ancient primate was nocturnal, diurnal, or cathemeral. | 4 | University of Warsaw, Poland |

| What big teeth you have! Sexual selection in rhesus macaques | animals, evolution, sexual selection, sexual dimorphism, anatomy, form and function, primate | In Cayo Santiago there is one of the oldest free-ranging rhesus macaque colonies in the world. Scientists have gathered data on these monkeys and their habitat for over 70 years. The program monitors individual monkeys over their entire lives, and when they die their bodies are recovered and skeletal specimens are stored in a museum. These skeletal specimens can be used by scientists today to ask new and exciting questions, for example, what traits are under sexual selection in this population? | 3 | Laboratory of Primate Morphology, University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus |

| Is it better to be bigger? | adaptation, animals, evolution, predation | Brown anoles are very small when they hatch out of the egg. Because of their small size, these anole hatchlings are eaten by many different animals, including birds, crabs, other species of anole lizards, and even adult brown anoles! Predators could be a significant force of natural selection on brown anole hatchlings. Juvenile anoles that get eaten by predators will not survive to reproduce. | 3 | Matanzas River, Florida |

| Is it dangerous to be a showoff? | adaptation, animals, evolution, predation, tradeoff, sexual dimorphism | Brown anoles are small lizards that are abundant in Florida. They have an extendable red and yellow flap of skin on their throat, called a dewlap. To communicate with other brown anoles, they extend their dewlap and move their head and body. Males have particularly large dewlaps, which they often display to defend territory or attract females. Females also have dewlaps but use them less often. How might natural selection on this trait differ between males and females? | 3 | Matanzas River, Florida |

| Anole’s new niche | adaptation, animals, evolution, niche, population, introduced species, native species, behavior, habitat | Humans have moved species around the world for centuries, and in Florida, this has led to the coexistence of the native green anole and the introduced brown anole. Scientist Yoel Stuart studied these lizards on islands in Mosquito Lagoon to test how green anoles change their habitat use when competing with brown anoles, finding that they adapt to coexistence by shifting higher into the trees when both species are present. | 2 | Mosquito Lagoon, Florida |

| Hold on for your life! Part I | adaptation, animals, disturbance, evolution, natural selection, genetic drift, hurricane | In the fall of 2017, a team of scientists from Harvard University and the Paris Natural History Museum visited Pine Cay and Water Cay in the Turks and Caicos Islands. They were there to collect data on a small local lizard, the Turks and Caicos anole, as part of a larger environmental conservation project. Unbeknownst to them, a storm was brewing to the south of the islands, and it was about to change the entire trajectory of their research. | 3 | Turks and Caicos, Caribbean |

| Hold on for your life! Part II | adaptation, animals, disturbance, evolution, natural selection, genetic drift, hurricane | The scientists needed to find out how lizards behave in hurricane-force winds. Obviously, they couldn’t stick around to watch lizards ride out a storm, so they designed a safe experiment that would simulate hurricane force winds. They bought the strongest leaf blower they could find, set it up in their hotel room on Pine Cay, and videotaped 40 lizards as they clung to a perch while slowly ramping up the leaf blower until the lizards were blown (unharmed) into a safety net. | 3 | Turks and Caicos, Caribbean |

| Sticky situations: big and small animals with sticky feet | adaptation, animals, chemistry, physics, scale, surface area | Sticky, or adhesive, toe pads have evolved in many different kinds of animals, including insects, arachnids, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals. The heavier the animal, the more adhesion they will need to stick and support their mass. For tiny species like mites and flies, tiny toes can do the job. Each fly toe only has to be able to support a small amount of weight. But when looking at larger animals like geckos, their increased weight means they need much larger toe pads to support them. | 4 | BEACON Center for the Study of Evolution in Action |

| Lizards, iguanas, and snakes! Oh my! | animals, biodiversity, disturbance restoration, urban | People have dramatically changed the natural riparian habitat found along rivers and streams. In many urban areas today, these riparian habitats are being rehabilitated with the hope of bringing back native species, such as reptiles. Reptiles, including snakes and lizards, are extremely important to monitor as they play important roles in ecosystems. Are rehabilitation efforts in Phoenix successful at restoring reptile diversity and abundance? | 3 | Salt River, Phoenix, Arizona |

| Urbanization and estuary eutrophication | algae, eutrophication, fertilization, marine, nitrogen, phosphorus, wetland, urban | Estuaries are very productive habitats found where freshwater rivers meet the ocean. They are important natural filters for water and protect the coast during storms. A high diversity of plants, fish, shellfish and birds call estuaries home. Estuaries are threatened by eutrophication, or the process by which an ecosystem becomes more productive when excess nutrients are added to the system. Parts of the Plum Island Estuary in MA may be more at risk from eutrophication due to their proximity to urban areas. | 4 | Plum Island Estuary, Massachusetts |

| Love that dirty water | environmental, urban, water, GIS, landscapes, impervious surfaces, ecosystem services | As green spaces are lost to make room for homes and businesses, there are fewer forests and wetlands to filter our drinking water. A team of scientists used the New England Landscapes Future Explorer to study this challenge for the Merrimack River, an important river for the people of New England. | 4 | New England |

| Toxic legacy | chemical pollution, community, human health, superfund | In Glynn County, Georgia there are four Superfund Sites on the National Priorities List by the US EPA. These sites are found to be particularly hazardous. Local scientists and community members wanted to compare chemical levels in Glynn County residents to the general population to see if living near Superfund sites may have increased their risk of exposure to dangerous chemicals. The team decided to focus on a few chemicals of interest, specifically toxaphene and PCBs, because of their history in the area and health consequences. | 4 | Glynn County, Georgia, USA |

| PFAS: Our forever problem | PFAS, water, teacher, pollution, watershed, Human impact | PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” are pollutants found in everyday items that build up in our environment and bodies. Researcher Natalia and local teacher Gary teamed up to study PFAS in Biscayne Bay, a vital ecosystem near Miami. Their work helps raise awareness about local pollution and connects science with the community. | 2 | Miami, Florida |

| Green Crabs: Invaders in the Great Marsh | animals, invasive species, substrate, wetland, erosion | The introduction of invasive species, such as the European Green Crab, poses a great threat to marshes. Digging behaviors of the Green Crab disturb sediments on the marsh floor and may have lead to the destruction of native eelgrass populations, which are sensitive to disturbance. Scientists aimed to identify locations where crab numbers are low and eelgrass can be restored. | 2 | Essex Bay, Massachusetts |

| The mystery of Plum Island Marsh | fertilization, fish, marine, mollusk, water, wetland | Salt marshes are among the most productive coastal ecosystems, and support a diversity of plants and animals. Algae and marsh plants feed many invertebrates, like snails and crabs, which are then eaten by larger fish and birds. In Plum Island, scientists have been fertilizing and studying salt marsh creeks to see how added nutrients affect the system. They noticed that fish populations seemed to be crashing in the fertilized creeks, while the mudflats were covered in mudsnails. Could there be a link? | 3 | Plum Island Estuary, Massachusetts |

| Does sea level rise harm saltmarsh sparrows? | animals, birds, sea level rise, climate change, disturbance, ecology, wetland | For the last 100 years, sea levels around the globe have increased dramatically. Salt marshes grow right at sea level and are therefore very sensitive to sea level rise. Saltmarsh sparrows rely completely on salt marshes for feeding and nesting, and therefore their numbers are expected to decline as sea levels rise and they lose nesting sites. Will this threatened bird species decline over time as sea levels rise? | 3 | Plum Island Estuary, Massachusetts |

| Keeping up with the sea level | climate change, disturbance, ecology, sea level rise, plants, substrate, wetland | Salt marshes are very important habitats for many species and protect the coast from erosion. Unfortunately, rising sea levels due to climate change are threatening these important ecosystems. As sea levels rise, the elevation of the marsh soil must rise as well so the plants have ground high enough to keep them above sea level. Basically, it is like a race between the marsh floor and sea level to see who can stay on top! | 3 | Plum Island Estuary, Massachusetts |

| Is your salt marsh in the zone? | climate change, ecology, plants, sea level rise, substrate, wetland | Beginning in the 1980s, scientist James began measuring the growth of marsh grasses. He discovered that their growth was higher in some years and lower in others and that there was a long-term trend of growth going up over time. Marsh grasses grow around mean sea level, or the average elevation between high and low tides. Are the grasses responding to mean sea level changing year-to-year, and increasing as our oceans warm and water levels rise due to climate change? | 3 | Plum Island Estuary, Massachusetts |

| The case of the collapsing soil | climate change, carbon, ecology, plants, phosphorus, sea level rise, respiration, substrate, wetland | The Everglades are a unique and vital ecosystem threatened by rising sea levels due to climate change. Recently scientists have observed in some areas of the wetland the soils are collapsing. What is causing this strange phenomena? Sea level rise might be stressing microbes, causing carbon to be lost to the atmosphere through increased respiration. | 4 | Everglades, Florida |

| Marvelous mud | ecology, environmental, fertilization, mud, phosphorus, substrate, water, wetland | Because mud is wet most of the time, it tends to have different properties than soil. Dead organic matter (partially decomposed plants) is an important part of mud and tends to build up in wetlands because it is decomposed more slowly under water where microbes do not have all the oxygen they need to break it down quickly. The amounts of organic matter may determine the levels of phosphorus and other nutrients held in wetland muds. | 2 | Fort Custer Recreation Area, Michigan |

| Marsh makeover | biodiversity, disturbance, ecology, greenhouse gasses, mud, plants, restoration, wetland | The muddy soils in salt marshes store a lot of carbon, compared to terrestrial dry soils. This is because they are low in oxygen needed for decomposition. For this reason they play a key role in the carbon cycle and climate change. If humans disturb marshes, reducing plant diversity and biomass, are they also disturbing the marsh's ability to sequester carbon? If a marsh is restored, can the carbon holding capacity also be brought back to previous levels? | 3 | Oak Island and Neponset Marsh, Boston, Massachusetts |

| Dangerously bold | animal behavior, animals, tradeoff, fish, predation | There are two main habitats that young bluegill sunfish can use to find food to eat – open water and cover. There is lots of food in the open water, but this habitat also has very few plants for bluegill to hide from predators, like the largemouth bass, so it’s not safe when bluegill are small! The cover habitat has less food, but it has lots of plants that make it hard for predators to see the bluegill. This sets up a situation where there are costs and benefits to using either habitat, called a tradeoff. | 1 | Pond Lab, Kellogg Biological Station, Michigan |

| Which guy should she choose? | animal behavior, animals, fish, mating | Mating behavior is intriguing to study because in many animal species, males use a lot of energy to attract a female. Yet some males are able to attract zero females and other males attract many females. What accounts for this difference? What about the way a male looks, moves, or smells attracts the female? A female could benefit from identifying “high quality” males that would serve as a good father to her offspring or that would make offspring that are attractive to females in the next generation. | 2 | Michigan State University lab and British Columbia, Canada |

| Fish fights | animal behavior, animals, fish, mating | Male stickleback fish fight each other to gain territories along the bottom of the shallow areas of a lake. In these territories, males build a nest out of sand, aquatic plants, and glue they produce from their kidneys. Males then attract females to their territories with courtship dances. If a female likes a male, she will deposit her eggs in his nest. Then the male will care for those eggs and the offspring that hatch. Perhaps more aggressive males are better at defending their territory and nests. | 2 | Michigan State University lab and British Columbia, Canada |

| Clique wars: social conflict in daffodil cichlids | animal behavior, animals, competition, fish | Daffodil cichlids live in social groups of several small fish and one breeding pair. The breeding male and female are the largest fist in the group, and the smaller fish help defend territory against predators and help care for newly hatched baby fish. About 200 social groups together make up a colony. Behavior within a social group may be influenced by the presence of other groups in the colony. For example, neighboring groups can be a threat because they may try to take away territory or resources. | 4 | The Ohio State University, Ohio |

| Fishy origins | citizen science, DNA, evolution, fish, PCR, marine | The population of striped bass in New Jersey is a mixed stock, meaning fish come together from different spawning grounds. Scientists want to understand where these fish come from in order to better manage their population. For their study, they needed DNA from many fish, so they turned to fishermen to help collect fin clip samples. They used these samples to identify the stocks migrating to New Jersey, and to determine if they was changing over time. | 4 | Monmouth University |

| Salmon in hot water | adaptation, animals, climate change, evolution, fish, genes, temperature, heredity, genetics | Salmon are important members of freshwater and ocean food webs. Climate change threatens salmon by warming the waters of rivers where they reproduce. To maintain healthy populations, salmon rely on cold, freshwater habitats and may go extinct as temperatures rise. However, some salmon individuals have higher thermal tolerance and are able to survive when water temperatures rise. Scientists want to know whether there is a genetic basis for the variation observed in salmon’s thermal tolerance. | 4 | University of Washington Hatchery, Seattle, Washington |

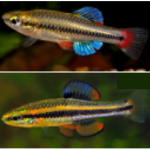

| Are you my species? | adaptation, animals, behavior, biodiversity, competition, evolution, fish, mating | How do animals know who to choose as a mate and who is a member of their own species? One way is through communication. Animals collect information about each other and the rest of the world using multiple senses, including sight, sound, and smell. Darters are a group of over 200 colorful fish species that live in lakes and rivers across the US. The bright color patterns on males may signal to females during mating who is a member of the same species and who would make a good mate. | 3 | University of Maryland, Baltimore |

| Why so blue? The determinants of color pattern in killifish, Part I | adaptation, animals, biodiversity, evolution, fish, genes, mating, heredity, genetics | In nature, animals can be found in a dazzling display of different colors and patterns. Even within one species there can be variation in color. For example, male bluefin killifish can have fins that are bright blue, red, or yellow. Becky, a scientist studying this species noticed an interesting pattern - males found in springs with crystal clear water have mostly red or yellow fins, while males found in swamps have bright blue fins. Becky wants to know, what is the driving mechanism behind this interesting pattern? | 4 | University of Illinois, Illinois |

| Why so blue? The determinants of color pattern in killifish, Part II | adaptation, animals, biodiversity, evolution, fish, genes, mating, heredity, genetics | To take a closer look at her data, Becky added information on paternal fin color into her analysis. | 4 | University of Illinois, Illinois |

| Bon Appétit! Why do male crickets feed females during courtship? | adaptation, animals, behavior, competition, insects, mating | In many species of insects and spiders, males provide females with gifts of food during courtship and mating. This is called nuptial feeding. These offerings are eaten by the female and can take many forms, including prey items the male captured, substances produced by the male, or parts from the male’s body. These gifts can cost the male a lot, so why do they give them? They may increase the male's chances of mating with a female, or they may help the female have more and healthier offspring. | 4 | Cornell University, New York |

| Stop that oxidation! What fruit flies teach us about human health | insects, model species, cell biology, genetics, cellular processes, oxidation | Each of our cells is home to mitochondria, tiny factories whose job is to turn the food we eat into the energy we need to live. But during this process oxidative damage can cause harm to everything in the cell. There are two ways that bodies can prevent oxidative damage: antioxidants and more efficient metabolic pathways. Biz looked at fruit flies with varying genetics for these two strategies and wanted to test whether the level of oxidative damage in eggs and sperm would influence how many offspring a female had. | 4 | Technische Universität Dresden |

| Did you hear that? Inside the world of fruit fly mating songs | animals, communication, insect, process of science, reproducibility, volume, social, behavior | Emma is a neuroscientist who is really interested in studying how brains are able to understand all kinds of communication. She uses fruit flies to figure out how brains process communication through sounds. Emma wanted to test whether lab conditions, such as volume of playback sounds and social isolation affected whether fruit flies in her lab performed a behavior called chaining that had been observed in other labs. | 2 | North Carolina State University |

| How to escape a predator | adaptation, animal behavior, animals, predation, physiology | Stalk-eyed flies have their eyes at the tip of eyestalks on the sides of their heads. Males with longer eyestalks are better at attracting mates – females find them sexy! However, long eyestalks may come at a cost. Males with long eyestalks may not be able to move easily and quickly, and could be easy targets for predators. Males also use a variety of behaviors to defend themselves against predators. Are these behaviors enough to compensate for long eyestalks? | 4 | Washington State University and University of Colorado, Denver |

| The flight of the stalk-eyed fly | physics, moment of inertia, adaptation, animals, flight, physiology | Moment of inertia (I) is an object’s tendency to resist rotation – in other words how difficult it is to make something turn. Stalk-eyed flies have eyes located on the ends of long projections on the sides of their head, called eyestalks. Because moment of inertia goes up with the square of the distance from the axis, we might expect that as the length of the flies’ eyestalks goes up, the harder and harder it will be for the fly to maneuver during flight. | 4 | Tel-Aviv University, Israel and University of Colorado, Denver |